The Darling Audiobook Summary

The Darling is Hannah Musgrave’s story, told emotionally and convincingly years later by Hannah herself. A political radical and member of the Weather Underground, Hannah has fled America to West Africa, where she and her Liberian husband become friends and colleagues of Charles Taylor, the notorious warlord and now ex-president of Liberia. When Taylor leaves for the United States in an effort to escape embezzlement charges, he’s immediately placed in prison. Hannah’s encounter with Taylor in America ultimately triggers a series of events whose momentum catches Hannah’s family in its grip and forces her to make a heartrending choice.

Set in Liberia and the United States from 1975 through 1991, The Darling is a political/historical thriller — reminiscent of Graham Greene and Joseph Conrad — that explodes the genre, raising serious philosophical questions about terrorism, political violence, and the clash of races and cultures.

Performed by Mary Beth Hurt

Other Top Audiobooks

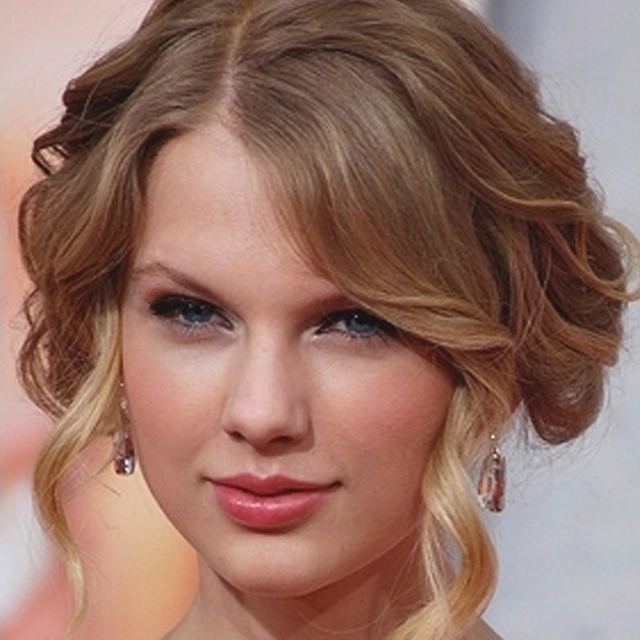

The Darling Audiobook Narrator

Mary Beth Hurt is the narrator of The Darling audiobook that was written by Russell Banks

Mary Beth Hurt, has received three Tony(r) nominations for her work on the New York stage, and has starred in such films as Affliction, Family Man, The World According to Garp, Chilly Scenes of Winter, and Interiors.

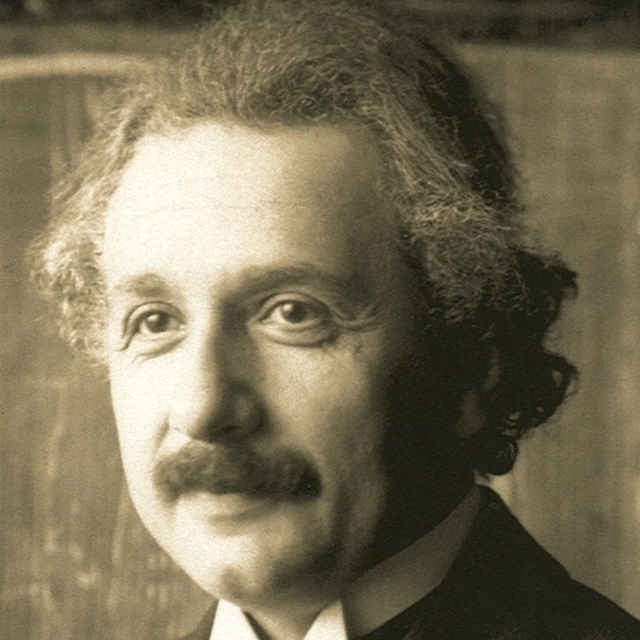

About the Author(s) of The Darling

Russell Banks is the author of The Darling

More From the Same

- Author : Russell Banks

- The Book of Jamaica

- Continental Drift

- Voyager

- Rule of the Bone

- Foregone

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

The Darling Full Details

| Narrator | Mary Beth Hurt |

| Length | 14 hours 10 minutes |

| Author | Russell Banks |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | December 21, 2004 |

| ISBN | 9780060824716 |

Additional info

The publisher of the The Darling is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780060824716.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

Kinga

April 30, 2019

A white male American writing a book with a white middle aged female narrator reminiscing over the time she lived in Africa seems like a potential minefield. But somehow, Banks pulled it off and didn’t lose any limbs on the mines. For many mediocre writers Africa seems ripe for picking, full of conflict and tragedy provides the story with high enough stakes to make up for the lack of talent on the writer’s part. But Banks does it well. He doesn’t use the continent as some shitty metaphor. He talks about Liberia, a country that’s a product of specific time and history and not some ‘unnamed African country’ that’s just a weird mash-up of stereotypes sprinkled with acacia trees and sunsets. Occasionally the passages explaining the history and politics of Liberia felt tiny bit too educational, but this is really a minor quibble. I’m not going to summarise the plot because there are already hundreds of reviews here that do just that, but I will say than other than Zack and the narrator’s father, there is almost a complete absence of white male protagonists in this book, which was very refreshing. All in all, this was a little like American Pastoral but better. I don’t know why the rest of the world seems to be sleeping on Russell Banks. He is a fine, fine writer. And he did a brave thing here, writing about stuff he had no business knowing about and weirdly pulling it off. He also opted for writing the thing in flashbacks, which removes some of the dramatic tension, as we already know how some of it ends. My favourite aspect of the book is how it treats the question of otherness - how the white narrator doesn’t seem to be able to overcome the ‘otherness’ of her Liberian husband, and then her own children who slip away from her and her feeble attempts at motherhood. I read a great phrase, I think it was in one of the interviews with Banks about this book – ‘the guilty innocence of white privileged people’, which describes white women in Africa well. This is what the half-sarcastic title of the novel refers to, and what I think when I see those Instagram posts. You know which ones.

Shane

February 07, 2017

This novel is a scarier version of Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral” in which the indulged upper middle class daughter rejects her comfortable surroundings in suburbia and joins a group of radicals to bring about a utopian socialist society in America, with disastrous consequences.Hannah Musgrave, the errant darling of the ‘70’s, is nearing her sixtieth year in the early 21st century, and is reflecting on where her idealism and search for purpose has led her. Firstly, she is not a particularly sympathetic or warm person. She has an irrational hate for her stay-at-home mother who only wanted the best for her daughter, she is a promiscuous bi-sexual who will sleep with anyone, including her husband’s driver while waiting for the said husband to join her after a family party, she has no particular maternal feelings towards her three mixed-race sons, or her husband, she cares for her chimpanzees more than for her human family, and she is blindly fearless, venturing into danger zones and crossing borders illegally without much thought for her safety, buoyed by the whiteness of her skin and the suspicion that the American authorities who want to imprison her back home will keep her alive in Africa.The story flows back and forth in time and location between America and Africa in five sections (there are no chapters) and we have to settle on the telling voice of Hanna who is the first-person narrator of the entire tale. We are introduced to her as she reflects on her prior life, while running a farm in the Adirondacks, a place of hard work and peaceful surroundings. She takes us on a tour of her life in the ‘70’s when she was a member of the Weather Underground, making bombs for the movement; she escapes arrest in America and makes it across to Africa, arriving in Liberia via Ghana. The history of the founding of Liberia, America’s cold-war colony in Africa, is covered in interesting detail. In Liberia, she marries a government official, Woodrow, and has three children by him. She finds purpose in caring for a band of chimpanzees that has been used by an American pharmacy for medical testing; Hanna persuades her husband to set up a sanctuary for the abused chimps and transforms the animals’ lives. Meanwhile, Liberia is heading towards civil war, with tribal chieftains jockeying for power. Fact mixes with fiction here for we are introduced to real-life warlords like Charles Taylor, Samuel Doe and Prince Johnson who become central characters in Hannah’s life and in her story. Woodrow and Hannah back the wrong horse and pay a terrible price, and Hannah’s dream of seeing the socialist utopia, once denied to her in the US, vanishes in Liberia as well, along with her family and her chimpanzees. It is through this loss that Hanna discovers her dormant maternal instinct and her love for family. What is gripping and unsettling is the level of violence that quickly descends on a country that was originally conceived as the returning homeland for free slaves from the US. However, as is to be expected, the freed slaves quickly became the ruling class, the 1%, encroaching on the lands of the natives, creating resentment and discord. “Liberia was created to solve a race problem in the US not a slave problem,” observes Hanna. She goes on to posit that, “Everything changes, except the principles of exploitation and use,” for the US, in an attempt to maintain control, pits one warlord against the other and supports the best one to serve them in his attempt to get rid of the others. The mysterious CIA agent Sam Clement shows up in Hanna’s life several times and, while protecting her, seems to be manipulating her for his own ends. Hanna’s drive into the interior to visit her husband’s tribal family for the first time is like a journey into the heart of darkness; these shades of Greene and Conrad provide layering and narrative thrust to the novel, despite it occasionally resembling the ramblings of an aging woman in search of a country.The challenges of a mixed racial and cultural marriage and its effects on the children are well drawn. Hannah never really has a visceral bond with her children, or with her husband, other than for a social and political one. And when those fragile bonds collapse everything and everyone is lost, and what is lost can never be regained.The irony is that as Hanna concludes her odyssey on Sep 10th 2001, she reflects that her narrative will pale in comparison to the much darker one that is about to unfold between America and its international satellites.

Fabian

February 07, 2021

"That's the real American Dream, don't you think? That you can start over, shape-change, disappear, and later reappear as someone else."The white priviledge is tested to its limit. This American darling is a rebel; our multi-named heroine goes to Africa, liberates chimpanzees, talks with the Liberian president, marries a black man and gives him children. She has the capability of doing so many things in the world--she is so well-developed as a character that her tragic story seems secondary. I want to pick your brain! What is it with women who adore primates (or dogs, or cats, or pets) and yet have no maternal feelings...?

Jordan

March 08, 2019

"I wondered if I had lost my mind...I thought, I could be a madwoman. And I wondered if I was standing there in the dark by the side of a narrow, unpaved road in the eastern hills of Liberia because somewhere back there, without knowing it, I'd lost touch with reality. Lost it in small bits, a single molecule of sanity at a time in a slow, invisible, irreversible process of erosion, and couldn't notice it while it was happening, couldn't take it's measure, until now, when it was too late."Banks easily ranks as one of my favorite writers. "Rule of the Bone" and "Affliction" are among my all time most loved novels. This one doesnt quite inhabit the same place those two do but it is still a great book. Banks always combines beautiful\interesting prose with exceptional imagination. As well as enaging the reader's intellectual curiosity. His books are always firing on all cylinders.

Leslie

August 30, 2007

the woman's point of view is so well done in this book that it's hard to believe it was authored by a man. i simultaneously loved and loathed the main character. the fact that it's historically accurate, and that charles taylor, who is featured prominently in the novel, has been in the press recently, make it all the more interesting.

Lena

September 07, 2007

I have incredibly disturbing thoughts about primates, and this book didn't help me out one bit.

Shannon

June 25, 2010

There aren't many Liberian authors - something like three, according to Wikipedia - and there aren't many books set there either. If you want a good idea of what the deal is with Liberia, where it is and what happened in its recent history, this is an excellent book for educating yourself. Hannah Musgrove is a well-educated American with a famous doctor for a father and a fluttering, apparently silly woman for a mother. It's the 60s, and just before finishing her medical degree she drops out and becomes involved in a political group. Over the years, while not seriously involved in terrorism, she tries to hide from the FBI and takes on an assumed name: Dawn Carrington. It is as Dawn that she later flees America, thinking her life is in danger, with her friend and fellow revolutionary, Zach. They go to Africa, to Ghana on the west coast. After several months there Hannah leaves Zach - who is making millions buying up African art from tribespeople and selling it at inflated prices to rich westerners - and crosses the border to Liberia, squeezed in between Côte d'Ivoire and Sierra Leone, where she heard a company connected to an American university is looking for trained medics to work in its laboratory, where they use chimpanzees as test subjects. Years later, now in her 50s and running an organic farm in the US, Hannah is driven to return to Liberia and revisit her guilt. She brings us with her, for the first time in her life telling someone the story of what happened - of meeting the Assistant Minister for Public Health, Woodrow Sundiata, and marrying him; of her three sons Dillon, Paul and William and how they became known as Worse Than Death, Fly, and Demonology; and the story of her chimps, how she rescued them and gave them sanctuary and then betrayed them. She feels her whole life is one betrayal after another, secret betrayals, betrayals to those who don't even realise it, and especially betrayals to her own self.She is like a different person in Africa, especially with Woodrow. Normally an aloof, cold person with minimal maternal instincts and, one could say, a man's mind, in scenes with Woodrow she seems helpless, almost silly, and submissive. It is not really a contradiction - humans are contradictory, anyway - but I am always fascinated by how we behave differently with different people. I didn't always like her or understand her, but I appreciated the difficulty she had in opening up and telling her story, and the honesty with which she tells it. It does, throughout, read like a true story, a memoir. There is something very ... National Geographic about the story. Some undeniable truth to it.Where Hannah's voice becomes less convincing, as a female protagonist, is in those sections where Banks tells us the history of Liberia - and it is Banks speaking at those times, like a history book, interesting but neutral, masculine, decisive. At such times Hannah disappeared, and I forgot all about her. But the history is very interesting to read, and very readable.Which reminds me: it took me a while to get into the style here. It seemed to settle down about halfway through, but in the beginning the very long, wandering sentences with multiple clauses really confused me. It's an older style - old-fashioned, I would call it. We write much cleaner these days, more coherently, with less information rammed into one sentence. I could call it a Victorian sentence structure - and I think I will! - for the Victorian era is famous for its cramped, over-crowded style, with many fussy little tables and ornaments and paintings crammed into rooms. Their prose reflected that, and it's here too, though much more refined and ordered and interjected with sharp short sentences as well. When I started reading it, I felt bogged down by the lengthy sentences and abundant adjectives, but after a while I ceased to even notice it.This is a story of several facets. It's the story of an American darling, who lives untouched and untouchable in "darkest Africa", a revolutionary, a political rebel at home who has no drive or desire to help or rescue the natives; nor does she feel terribly moved by their plight, by the corrupt government taking advantage of them. She recognises the contradiction, and also - with the mature hindsight that comes with telling the story of your past - realises how selfish she was even as a revolutionary fighting the state in 60s America.It's also the story of a country haunted by ghosts, torn apart and shat on and forgotten. Liberia bleeds all over the pages, and if you've read any other books about civil wars and corruption and western corporate takeovers in Africa, it will be a familiar story to you. As such, it's highly politically charged, but not even surprising in it verdict - we've heard it all before. It's still truth, of its own kind, but repeated so many times in so many countries it seems lethargic in its truth. Liberia will be just as forgotten after having been heard, and it knows it. Banks brought it alive, briefly, within these pages; after which it will sink back into the bog, just one more horrific story of what humans are capable of.And it is the story of the "dreamers", as Hannah calls the chimps. In a way, the animals are metaphors for the people of Africa, abused, captured, sold, taken advantage of, homeless, caged, dependent on aid, hunted down and killed and eaten. Converted. Never left alone to survive in their own way. These animals will damn near break your heart, and I almost hated Hannah for abandoning them - and for collecting them in the first place. But it's misplaced anger; she rescued baby chimps from their cages in the market, where they were sold to live in labs as test subjects, or pets overseas. I get angry at Hannah because she's there, and she cares, and doesn't do enough, and because it's blind anger at how we treat other animals and the planet in general.I was disappointed that the chimps didn't have a stronger presence in the novel - they seemed rather to serve as a premise for Hannah. Considering how awful so many of the characters were - I can't think of any that I really liked; Woodrow especially made me very uncomfortable - the chimps seemed the most humane of all of them. (Did you know we share 99% of the same genes? And that female humans and female chimps are more alike, genetically, than female humans and male humans, and vice versa? Fascinating stuff.)This is a story rich in detail, in action, in self-reflection and political history. It is a story of a bad country gone rotten, and of a woman facing up to herself, her flaws, her inconsistencies. It's a story of American history as much as Liberian, and it's well worth reading.

Dayna

December 19, 2008

This book doesn't take on life until 1/4 way in, when Hannah Musgrave has returned to Liberia (to which she first fled in order to escape her possible imprisonment as a member of the the Weather Underground) to confront certain "ghosts" from her past. Russell Banks, to his credit, keeps these ghosts rather vague - does she return to confront the spirits of the chimpanzees who had fallen under her care and who perished because of her choices? Or to find the sons she had abandoned, the sons who had become boy soldiers and whose fate we do not yet know? Banks makes it clear in the narrative that Hannah throughout the novel can never quite tell an "accurate" story of what had happened since most circumstances of her life has necessitated her decisions to vary the truth, to survive by taking on different personas and hiding who is really is until she is no longer sure who that person is. This complexity is partly what makes me like this book because as the reader we are taken on the same journey as she, Hannah, in determining her loyalties, her understanding of herself and whether she deserves or will ever receive redemption for her actions.Some critics have remarked that Banks fails with this novel by attempting to write from a woman's perspective - for what woman could be so emotionally detached and feel so little towards her own children? Ironically, this is one of the successes of the novel, which gives it its emotional grip. As people, why do we find this so hard to believe, that a woman can be that way? There are moments throughout when Banks addresses Hannah's guilt for feeling more towards the chimpanzees than her own children and for saying goodbye to people and places so easily, but not without the remorse which comes later, maybe too late, but maybe not. I look forward to reading the rest of the novel.Final note: I welcomed Banks' use of Liberia as the background for this novel, especially since it educated me in America's, as usual, negative role in its history. What I did not find believable was Hannah's part in the Weather Underground. It didn't quite feel like she was in serious danger for her bit part - not enough to feel like she would have to remain forever in hiding.

Ann

June 04, 2017

What starts out with an almost-elderly woman in a pastoral setting on a farm in the Adirondacks soon becomes an African adventure for a young American woman who rebels against her family and her country. Hannah Musgrave, an unsympathetic character, if a reliable narrator tells her story and a harrowing one it is. After radical bomb-making in the U.S., the young Hannah is forced to flee the country and ends up in a roundabout fashion in Liberia.Here she seems to abandon her political ideals. It seems to me that she was alone and frightened and grasped at Woodrow, a minor government official, for security. She found it. But only temporarily. Married with three sons, Hannah still never seems to belong. She only feels comfortable with her dreamers in their sanctuary.The sudden violence that sweeps through the country took my breath away. Hannah's life is torn asunder.While the warlords battle it out in the small country that was founded for ex-slaves, the theme of belonging or not overshadowed all else for me.Unforgettable.

Paul

May 11, 2017

Hannah is ‘the darling’ of American wealth and privilege , and the story charts her life from early anti-establishment activity in the seventies through her life in ,and return to, Liberia in turbulent times. It’s thoughtfully written and holds you captive right up to the end. It has a lot to say about Hannah ,not much of which is good , but it also seems to offer a reading that mirrors her with American Foreign policy in the region. Or am I just reading too much into it? Banks is always worth reading.

Krista

September 11, 2014

This might be a spoilerish review, better read after the book. As we meet Hannah Musgrave, she's an organic farmer in her fifties; a woman haunted by a past that she is finally willing to confront. In a first-person, confessional tone, Musgrave brings the reader along as she returns to Africa; revisiting the climax of her early life. Along the way, we learn that Musgrave was the privileged daughter of a semi-famous liberal activist father and a Junior League/charity works mother; a civil rights agitator in college; a fugitive member of the Weather Underground during the 70's; and after finding herself in Liberia, the wife of a mid-ranking minister in the corrupt government of William R. Tolbert, Jr. It is from that last pampered position that Musgrave has a front row seat to the coups and countercoups that led to the grisly Liberian Civil War of the 1980's. After visiting Liberia once again -- ostensibly to find traces of the three sons she left behind when she first fled the country (even though she had known at the time that they had become child soldiers in the revolution) -- Musgrave flies back to NYC on September 11, 2001. (I) made my way home to a nation terrorized and grieving on a scale that no American had imagined before, a nation whose entire history was being rapidly rewritten. In the months that followed, I saw that the story of my life could have no significance in the larger world. In the new history of America, mine was merely the story of an American darling, and had been from the beginning. Reading The Darling, I thought the book was about one thing (the life story of a former hippy and how her idealism had no practical effect in the real world), but by having the story end on 9/11, it became something different (a record of a time when people could be idealists and protest against their own government without violating the Patriot Act). This turnabout was so extreme that I needed to find out more about Russell Banks and his motivation, and after learning that this was his first post-9/11 book, I found this interview: For me the central theme, and it's one I've gone back to in other books in other ways, is the unintended consequences of good intentions. She is in many ways emblematic even of American foreign policy if you want. Today in other areas of the world, especially in a post-9/11 world, we are suddenly filled with good intentions and are killing people as a result and probably radically altering our society in the process in a very dangerous way. You can look at the history of Liberia for instance: the creation of Liberia. In its conception there were good intentions lying behind it. There was a nefarious and a dark side to those good intentions as there almost inevitably are because pure motives don't exist. The bloody civil war that started in 1980 is in fact the unintended consequence of good intentions, which started in the 1820s. Let's send them back to Africa, make the world safe and pretty, make it civilized and Christianized, and at the same time solve our race problem here in the United States with all those free blacks appearing in the streets of Philadelphia or New York. That to me is the central theme running through the book. I like to think of Hannah as emblematic of that; her life is that, the good intentions of the 1960s and 1970s, and the unintended consequences of it that she experiences very directly. If the good intentions (and their unintended consequences) of the 60's and 70's was the main point of The Darling, it's frustrating that the character of Hannah Musgrave is so unlikeable. Even though she has the full support of her parents, Musgrave is rather cruel and dismissive of them in her years underground; she is blasé about who might get hurt during her Weathermen years of making pipebombs and false passports; she's a sexual user who admits that her attraction to black men is probably a form of reverse racism; she is repulsed by the traditional-living Africans that she had a vague intention of helping; she's fine working in a medical lab that does experiments on chimps for the enrichment of some big American Pharmaceutical company; she feels no attachment to her husband and children; and she realises too late that during all of the years she spent as the wife of a health minister, she could have been improving the lives of the urban Liberians by teaching them hygiene, or reading, or other important life skills. Essentially, Musgrave is a narcissist, and every "good intention" has herself as the intended recipient, dismissing the whole hippy-movement thus: When you abandon and betray those with whom you empathize, you're not abandoning or betraying anyone or anything that's as real as yourself. Taken to its extreme, perhaps even pathological, form, empathy is narcissism. Despite not liking her, I did buy the character of Hannah Musgrave. It's not often that I find female protagonists as written by male authors believable, but Musgrave was plausible because she had so many masculine traits (sexual exploitation, a non-nurturing nature, swaggering self-confidence). And although it's meant to explain Musgrave's own diffidence, I think most young mothers have experienced the following to some degree (even if we're not supposed to admit it):First you think, This is what my life is now. This is who I am. My life is this endless grinding and thumping, being ground and thumped. Then you think, no, my life now will be spent floundering clumsily inside and around the thick waters of my own strangely misshapen body. No, it's shitting red-hot coals to give birth. Turning myself into an inverted volcano. Then you think, no, I'm the leaking person who gives her sore breasts over to another creature's sucking mouth, and when the baby is filled, cleans up its vomit, piss, and shit.Over and over, the same cycle, month after month. This is what my life is now, you think. This is who I am. And everyone, especially if she's a woman, assures you that you will love all the stages of this life, that each stage will make you feel for the first time increasingly like a fully realized woman, an expanded and deepened version of your old self.So, I did believe Hannah, was intrigued by the revelation of Liberia's sad history, and enjoyed the format of skipping back and forth through time (so that, as Hannah explains, we can get to know her and not judge her too harshly when we get to her major failings). I liked everything to do with the chimpanzee sanctuary that Musgrave oversaw (and could almost understand why she preferred her "dreamers" to actual people). But I don't know if I loved this book -- there may have been just too many things going on: too much about her parents; too much about chimps (that could have been its own book); too much about her life today; all of these could have been cut out without losing anything. And there were just too many coincidences (and these are really spoilers): Hannah finally reuniting with her parents a week before her father dies; dropping in on Carol and finding Zack living there; Zack having been in federal prison with Charles Taylor; Hannah acting as a useful dupe for the CIA when she jailbreaks Taylor; flying into NYC on 9/11. And, while I understand that part of the theme of this book is America's interventions abroad and their unintended consequences, there was something uncomfortable (more reverse racism?) about the fate of an entire African nation being affected by the naive actions of one white American.I can appreciate what went into The Darling: it's sweeping and smart and very well-constructed, but it totally lacked heart. I couldn't truly identify with or root for the narcissistic protagonist, and if she was supposed to represent the regretfully lost idealism of an earlier generation, it's not shown to be something to lament passing. It wasn't the hippies who led the Civil Rights Movement (although I'd imagine Black America appreciated what support they received); it wasn't the hippies who ended the Vietnam War; hippies never changed the world one bit; were they all darlings; dilettantes? In the end, hippies feel like they've done pretty well if they end up wearing silver ponytails and granny glasses on their organic farms in upstate New York (this is Banks' evaluation from the above interview), but I have to wonder if that was worth it (and especially for the Weathermen). I did not love this book but I'm giving it four stars because it's so much better than most of my three star reads.

JoAnn/QuAppelle

June 25, 2008

The main character was so despicable!As I read this book, I wanted to grab Hannah/Dawn and smack her face. What a despicable character....and what a writing genius Banks is, at least in this book, to make me feel this way. However, I like linear novels, so Banks' jumping back and forth in time is NOT my favorite device. This is not a spoiler: Wouldn't the book have been just as effective if the reader had not known at the beginning that Hannah escaped from Liberia and got back to the States? What is the point of starting the book out with her being 50- something and living in Vermont? For me, doing this totally eliminates any dramatic tension that this reader might experience. Back to the main character: I knew people like Hannah- I called them "convenient militants". She was also egotistical, self-absorbed, selfish, and overly impressed with herself and her so-called role in Liberia. For all her desire to make a better life for those who were oppressed, she was totally uninvolved and detached from daily life in her adopted country. In my opinion, ahe had no redeeming qualities....no matter what happened,it was ALL ABOUT HER. When Hannah went back to her mother's, I had to laugh at a comment she made about her mother being so self-centered. Talk about the apple not falling far from the tree!!! One thing that really bothered me----I know this is fiction, but I found the coincidence of Charles Taylor just happening to be in the same jail as Hannah's old friend to be a bit forced. And the fact of Hannah being in New Bedford just at this exact time was highly improbable. I guess that is artistic license but it rang very false to me. I have no idea of how accurate this novel is, but it has spurred me on to learn more about Liberia

Dennis

September 11, 2014

It's not often that you get a book set in Liberia, and even more improbable to find it tied to the SDS and Weather Underground movements of the 60's and 70's but that's what happens here. A very entertaining read and very informative on the development of Liberia and its first civil war but for me, there was one defect, all too common in a book where the author writes in the voice of the opposite gender and that was that the narrator sounded a little flat to me. Instead of empathizing with the poor choices she'd made, I found myself a bit annoyed with her whining at times. When you screw up, you screw up and all attempts to somehow justify your choices begin to send pathetic, particularly if you keep returning to those poor excuses. However that may only be my take on it and in no way takes away from the fact that the book was well worth the time spent in reading it.

Julie

July 14, 2008

A brilliant and devastating work that shows through the fictional life of its female protagonist the real horrors of revolution and dictatorship in Liberia. Banks is a master writer who can reveal both the lovable and despicable in his characters and bring alive a piece of history through a story that is utterly believable.

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.