The Dispossessed Audiobook Summary

“One of the greats….Not just a science fiction writer; a literary icon.” – Stephen King

From the brilliant and award-winning author Ursula K. Le Guin comes a classic tale of two planets torn apart by conflict and mistrust — and the man who risks everything to reunite them.

A bleak moon settled by utopian anarchists, Anarres has long been isolated from other worlds, including its mother planet, Urras–a civilization of warring nations, great poverty, and immense wealth. Now Shevek, a brilliant physicist, is determined to reunite the two planets, which have been divided by centuries of distrust. He will seek answers, question the unquestionable, and attempt to tear down the walls of hatred that have kept them apart.

To visit Urras–to learn, to teach, to share–will require great sacrifice and risks, which Shevek willingly accepts. But the ambitious scientist’s gift is soon seen as a threat, and in the profound conflict that ensues, he must reexamine his beliefs even as he ignites the fires of change.

Other Top Audiobooks

The Dispossessed Audiobook Narrator

Don Leslie is the narrator of The Dispossessed audiobook that was written by Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (1929-2018) was a celebrated author whose body of work includes 23 novels, 12 volumes of short stories, 11 volumes of poetry, 13 children’s books, five essay collections, and four works of translation. The breadth and imagination of her work earned her six Nebula Awards, seven Hugo Awards, and SFWA’s Grand Master, along with the PEN/Malamud and many other award. In 2014 she was awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, and in 2016 joined the short list of authors to be published in their lifetimes by the Library of America.

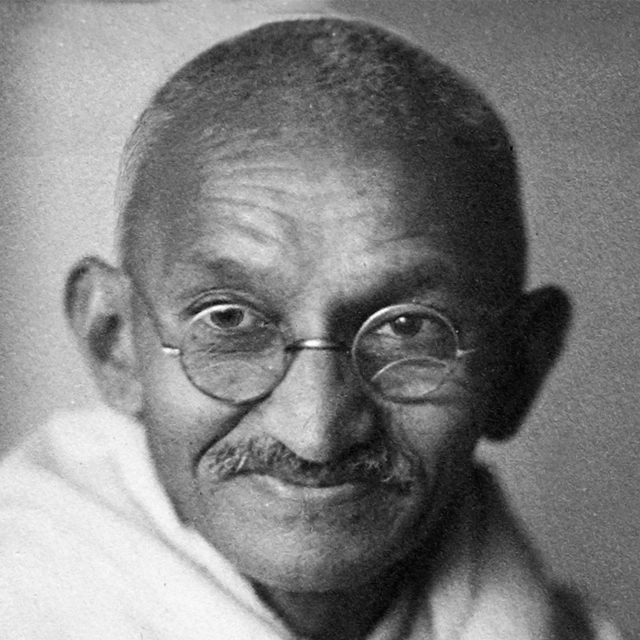

About the Author(s) of The Dispossessed

Ursula K. Le Guin is the author of The Dispossessed

More From the Same

- Author : Ursula K. Le Guin

- Always Coming Home

- Wonderful Alexander and the Catwings

- The Wind’s Twelve Quarters

- Lavinia

- Tehanu

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

The Dispossessed Full Details

| Narrator | Don Leslie |

| Length | 13 hours 25 minutes |

| Author | Ursula K. Le Guin |

| Category | |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | September 14, 2010 |

| ISBN | 9780062025449 |

Additional info

The publisher of the The Dispossessed is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780062025449.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

Manny

September 24, 2014

First of all: if you haven't already read The Dispossessed, then do so. Somehow, probably because it comes with an SF sticker, it isn't yet officially labeled as one of the great novels of the 20th century. They're going to fix that eventually, so why not get in ahead of the crowd? It's not just a terrific story; it might change your life. Ursula Le Guin is saying some pretty important stuff here.So, what is it she's saying that's so important? I've read the book several times since I first came across it as a teenager, and my perception of it has changed over time. There's more than one layer, and I, at least, didn't immediately realize that. On the surface, the first thing you notice is the setting. She is presenting a genuinely credible anarchist utopia. Most utopias are irritating or just plain silly. You read them, and at best you shake your head and wish that people actually were like that; or, more likely, you wonder how the author can be quite so deluded. This one's different. Le Guin has thought about it a lot, and taken into account the obvious fact that people are often selfish and stupid. You feel that her anarchist society actually could work; it doesn't work all the time, and there are things about it that you see are going to cause problems. But, like the US Constitution (one of my favorite utopian documents) it seems to have the necessary flexibility and groundedness that allow it to adapt to changing circumstances and survive. She's done a good job, and you can't help admiring the brave and kind Annaresti.Another thing you're immediately impressed by is the central character, Shevek. Looking at the other reviews, everyone loves Shevek. I love him too. He's one of the most convincing fictional scientists I know; I'm a scientist myself, so I'm very sensitive to the nuances. Like his society, he's not in any way perfect, and his life is a long struggle to try and understand the secrets of temporal physics, which he often feels are completely beyond him. I was impressed by the alien science; she gives you just the right amount of background that it feels credible, but not so much that you're tempted to nit-pick the details. You're swept up in his quest to unify Sequency and Simultaneity, without ever needing to know exactly what they are. And his relationship with Takver is a great love story, with some wonderfully moving scenes. There's one line in particular which, despite being utterly simple and understated, never fails to bring tears to my eyes. As you also see in The Lathe of Heaven, Le Guin knows about love.What I've said so far would already be enough to qualify this as a good book that was absolutely worth reading. What I think makes it a great book is her analysis of the concept of freedom. There are so many other interesting things to look at that at first you don't quite notice it, but to me it's the core of the novel. What does it mean to be truly free? At first, you think that the Annaresti have already achieved that; it's just a question of having the right social structures. But after a while you see that it's not nearly as straightforward as you first imagined. Real freedom means that you have to be able to challenge the beliefs of the people around you when they conflict with what you, yourself, truly believe, and that can be painful for everyone. But it's essential, and it's particularly essential if you want to be a scientist; I know this from personal experience. Another theme that suffuses the book is the concept of the Promise. If you can't make and keep promises, then you have no influence on the future; you are locked in the present. But promising something also binds your future self. There are some deep paradoxes here. The book folds the arguments unobtrusively into the narrative, and never shoves them in your face, but after a while you see that they are what tie all the strands together: the anarchist society, the science, the love story, the politics. It's a much deeper book than you first realize. As I said, it might change your life. It's changed mine.

Joe

November 29, 2007

Oh, Ursula. No longer will I love you in a vaguely ashamed manner, skulking through chesty-women-blow-shit-up-also-monster! book covers in the sci-fi/fantasy aisles with a moderate velocity as though I am actually trying to find Civil War biographies but am amusingly lost amongst all these shelves, that's so like me, need a GPS for Borders. Today, I will begin loving you publicly, proudly, for you are the Anti-Ayn Rand. You do not skullf**k Ayn Rand and make her your bitch, no, too easy. You take her gently by the hand, lay down beside her pruned, mummified body and have entirely consensual, non-hierarchical, process-centered sexual intercourse like a paragon of second-wave lesbian feminism.Ursula, you make me want to be a straighter man.

s.penkevich

January 12, 2023

‘You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.’Reading The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin was likely the biggest literary event of the year for me. This endlessly quotable book gripped me on every level and the way Le Guin can examine and explain ideas is so fluid, especially how she crafts such functioning worlds for her characters and ideas to move around in. Told in a rotating timeline with the past events catching up to those in the present (a narrative structure that functions as an expression of several of the book’s themes), we follow Shevek’s life as a physicist growing up in a anarchist-style society and then his time on a highly capitalist society on the planet Urras as he struggles to develop a working theory of time that incorporates both cyclical and linear time. Shevek’s experience juxtaposes the two societies as he realizes his ideas can be very dangerous in a society that only values profit and power. So many intelligent discussions of this book already exist that I likely have nothing to add, but I love this book so much and wanted to get my thoughts down. Through exploring the multiple meanings of the word “revolution,” Le Guin explores society and sociolinguistics in this incredible book about freedom and sharing the struggles of others to help build a better world.‘At present we seem only to write dystopias,’ Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, ‘perhaps in order to be able to write a utopia we need to think yinly.’ She was speaking, of course, about the concept of yin and yang, something that seems present in much of her work and especially highlighted by the two societies in The Dispossessed. Le Guin contrasts two societies, the planet Urras full of war and stark inequality and the anarchist society that settled on the moon Anarres, and uses the juxtaposition to examine how to theorize on reconfiguring social systems to be ethical and free. Though as states the subtitle in original publications, this is An Ambiguous Utopia and Le Guin is not here to give answers but to tell a story within the landscape of these ethical musings, one that should give birth to further thought, further theory and further striving to better the world. In an interview with Anarcho Geek Review, Le Guin said ‘When I got the idea for The Dispossessed, the story I sketched out was all wrong, and I had to figure out what it really was about and what it needed. What it needed was first about a year of reading all the Utopias, and then another year or two of reading all the Anarchist writers.’ She admits the book is heavily based in the writings of Lao Tzu (his book Tao Te Ching has been translated by Le Guin), Paul Goodman, and Pyotr Kropotkin, though other anarchist thinkers such as Emma Goldman and Mikhail Bakunin seem to also inform many of the ideas present as well. Le Guin was heavily influenced in all her works by taoism, and Paul Goodman’s work often showed taoism as a contributor towards a coherent theory of anarchism. The Dispossessed details a style of taoist anarchism that is similar to those expressed in another Le Guin novel, The Lathe of Heaven, one being that a revolution cannot rely on political or authorities but on a deep engagement between the individual and the world around us where we become the change we wish to see in the world. ‘The freedom to think involves the courage to stumble upon our demons.’-Simone Weil, On the Abolition of All Political PartiesThe change Shevek wishes to see originates in his work with time theories but he quickly realizes how immersed in political struggle his life is. Le Guin fans are treated to the creation of the ansible, a communication device that is present in the Hannish books, particularly The Left Hand of Darkness, a device many players on the planet Urras are trying to help him create it but also to control it. His studies on time require him to combine two different concepts of time: Sequency and Simultaneity, with the former endorsing a linear concept of time and the latter for non-linear time, such as recursive theories. Shevek must transcend constructs that have been considered rational thought to a more radical theory of time, as a sort of postmodernist anarchist that must hold both modes of time in his mind at once in order to achieve his goal. F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that ‘the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function,’ so I suppose we can rightfully claim Shevek as a genius here. His biggest hurdle, it would seem, is less the creation of his working theory but the hurdles of power. On Anarres he is stifled by others who can block his publication or wish to take the credit, while on Urras it will be used for profit, power, and likely warmaking.‘Free your mind of the idea of deserving, the idea of earning, and you will begin to be able to think.’Shevek’s Odian society on Anarres is set-up to have ‘ no law but the single principle of mutual aid between individuals,’ (Mutual Aid by Pyotr Kropotkin being an largely influential work in anarchist theory and this novel). It is a harsh planet where horizontal organization has kept the society going, with people assigned to rotating jobs to best befit the current needs to keep the society going. They have no sense of private property and everything is a community (even families where there are no individual family units). This contrasts with Urras, which is a capitalist society where profit and private property is the primary function (hence why the Odians refer to them as ‘propetarians’). While the harsh climate and scarcity of resources on Anarres may have been fertile soil for their style of society to work, they have developed a concept of communal society that see’s it’s function as one to remove unnecessary suffering. ‘We can't prevent suffering. This pain and that pain, yes, but not Pain. A society can only relieve social suffering - unnecessary suffering. The rest remains. The root, the reality.’ This contrasts with Urras where all the bad-faith bootstraps mythologies created a hierarchical society where chasing profits removes suffering from the elites but displaces it onto the lower classes, the very sort of thing the Odians fled to establish their society in the mining colonies on the moon Anarres. ‘To make a thief, make an owner; to create crime, create laws.’-Odian teaching‘The essential function of the state is to maintain the existing inequality’ wrote activist Nicolas Walter in About Anarchism, which is why Odians do not believe in any forms of State-ruled government. There are several different government styles on Urras, though Shevek sees them all as inevitable towards oppression. ‘The individual cannot bargain with the State,’ Shevek says, ‘the State recognizes no coinage but power: and it issues the coins itself.’ Even the thinly-disguised Soviet Russia country in the book (which is currently engaged in a proxy war with the strong capitalist country) repulses Shevek for still maintaining a government over the people telling their envoy ‘the revolution for justice which you began and then stopped halfway.’ Freedom, he argues, only comes from a collective society. To the idea of individualism, Shevek notes that what is society but a collective of individuals working towards a common goal.'You put another lock on the door and call it democracy.'While the glamour of Urras is charming to him at first, he begins to see how rotten it is at the core and how profit figures into everything, especially when his ideas are dismissed and questioned why he should be allowed to pursue them without a clear profit motive. ‘There is nothing you can do that profit does not enter into, and fear of loss, and wish for power. You cannot say good morning without knowing which of you is 'superior' to the other, or trying to prove it. You cannot act like a brother to other people, you must manipulate them, or command them, or obey them, or trick them. You cannot touch another person, yet they will not leave you alone. There is no freedom.’While Shevek sees that because his people own nothing, they are free, those of Urras only have the illusion of freedom, he discovers, and in their quest to own things are thereby owned by them. ‘They think if people can possess enough things they will be content to live in prison’ Shevek thinks. Interestingly enough, early in his youth he and his friends learned the concept of prison and decided to play-act it but the reader quickly realizes ‘it was playing them.’ They are so enticed into their roles they are okay with harming each other (‘they decided that Kadagv had asked for it’) which makes for excellent commentary on how hierarchy breeds violence and oppression. ‘All the operations of capitalism were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion as barbaric, as elaborate, and as unnecessary,’ Le Guin writes of our hero. To create this effect, Le Guin has done something extraordinary here by making sociolinguistics highly important to the novel as indicators of the different societies. Drawing on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that the structure of a language influences the native speaker’s perceptions and categorization of experiences. The linguistic relativity is seen in the Anarras language of Pravic, where there is an aversion to singular possessive pronouns since they imply property. Sadik (Shevek’s daughter) for instance, calls him The Father not, my father, or says ‘share the handkerchief I use’ instead of my handkerchief. The language removes a lot of ideas of shame and patriarchy as well. ‘Pravic was not a good swearing language. It is hard to swear when sex is not dirty and blashpemy does not exist.’ Even the language of Urras is alarming to Shevek. His language removes any class-based hierarchy, so prefixes such as being called Dr. are offensive to him. He notices that class dialects occur on Urras as well, with his servant, Efor, code-switching between them. THe upper classes on Urras tend to have a drawl to their words. Late in the novel when the Terran ambassador arrives (it’s a Hannish book, of course the Terrans show up), it is said of Pravic that it was ‘the only rationally invented language that has become the tongue of a great people.‘ Written in the 60s, the language aspects feel relevant to today’s world when there is much political discourse on the way language morphs with a changing society. Language and the way we apply it is culturally influenced, and linguistic signifiers can be reflective of culture, and there is often much argument online if adapting language to fit modern needs is social conditioning or simply just using the malleability of language to be more productive or empathetic in the rhetoric we choose to apply in various situations (Le Guin, for the record, frequently defended the singular ‘they’ in language [see the final question in the previously mentioned interview]). David Foster Wallace wrote at length in his essay Authority & American Usage on social and political influences on debates over descriptive vs prescriptive grammar changes, and to see Le Guin incorporate sociolinguistics as signifiers for her two societies is quite wonderful.‘I want the walls down. I want solidarity, human solidarity.’The language barrier is a great example of how The Dispossessed toys with concepts of walls. The novel opens with a description of a wall and the question of how inside/outside being on of perception. Shevek frequently comments on how he wishes to tear down walls, and his message of revolution is not one of taking the power back but of abolition of power. No walls, no barriers, only unity. For that reason he cannot allow his device to be used for war, or nationalistic purposes as he realized those on Urras will want (he sees how racism occurs due to concepts of walls while there).’You the possessors are the possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes—the wall, the wall!’Revolution has many meanings in this novel. The overthrow of the system or a cycle such as his concept of time. But it is also shown that revolution isn’t a single act but a continuous cycle as well. The Terrans say they have seen it all, tried everything, but ‘if each life is not new, each single life, then why are we born.’ There must be a constant striving towards betterment, reshaping, undoing, rebuilding. Anarres is not perfect either, hence the ambiguous utopia, and there must be the drive to keep going. Hence the open ended conclusion to the novel.'Society was not against them. It was for them; with them; it was them.'The Dispossessed is such a magnificent work. The ideas are great, the writing is sharp and engaging, and there is an epic feel to the story as it draws on structures such as the hero’s quest. I love how Le Guin tends towards a style of storytelling via anthropology, and the political discourse in this only heightens my enjoyment of it. She was a brilliant writer and this book is such a powder keg of extraordinary thoughts wrapped in a a science fiction narrative. It is so endlessly quotable you could practically build a religion out of it. All the stars in the Goodreads cosmos aren’t enough to award this novel for how much I love it.5/5‘I come with empty hands and the desire to unbuild walls.’

mark

April 07, 2015

Why America Is Full of Toxic Bullshit and Why Ambiguous Utopias Need to Check Themselves Before They Wreck Themselves Going Down the Same Fucked-Up Path by Ursula K. Le Guin.this excellent novel-cum-political treatise-cum-extended metaphor for the States lays its thesis out in parallel narratives. in the present day (far, far, far in the future), heroically thoughtful protagonist Shevek visits the thinly-veiled States of the nation A-Io on the planet Urras in order to both work on his Theory of Simultaneity and to pave the way for change on his homeworld. in chapters that alternate with this trip to Urras, we watch Shevek grow from boy to man on the anarcho-communist Anarres - the "Ambiguous Utopia" of the novel's subtitle. Urras and Anarres form a double-planet system within the Tau Ceti star system. The planets have a difficult relationship: 150 years prior, revolutionaries from Urras were given the mining planet of Anarres in order to halt their various revolutionary activities throughout the Urran nations. Upon establishment of their colony, Anarres cut off all but the most basic contact and trade with the despised "propertarians" of Urras.The Dispossessed is a fiercely intelligent, passionate, intensely critical novel - yet it is also a gentle, warm and very carefully constructed novel as well. ideas do not burn off the page with their fiery rhetoric - everything is deliberately paced; concepts and actions and even characterization are parsed out slowly. its parallel narratives are perfectly executed, with different plot themes and character backgrounds brought up, expanded upon, and often reflecting upon each other. ideas are unspooled in multiple directions and serve to continually challenge reader preconceptions. overall this is not a novel that quickens the pulse (although there is some of that) but is instead a Novel of Ideas. if you are not in a contemplative mood, if you have no interest in systems of government or human potential or theoretical physics, then this is probably not the novel for you. it is a book for the patient reader - one who actually enjoys sitting back and thinking about things. Le Guin's prose does not jump up at you; nonetheless, she is a beautiful writer - equally skilled with the little details that make a scene real and and with making the Big Concepts understandable to dummies like myself. and Le Guin is a sophisticated writer. she seems constitutionally unable to write in black & white - everything is multi-leveled, nothing is all bad, nothing is perfect. humans are fallible; ideas are fallible. everything must change and yet the past is ever a living part of the present.America as A-Io is where much of Le Guin's passion is displayed. however, the time spent in A-Io (roughly half the novel due to the alternating chapters) did not exactly challenge me. perhaps because i am already critical of the good ole U.S. of A., and have engaged in plenty of political shenanigans throughout my life, i wasn't reading anything new. i am the choir to whom the novel preached. still, i'm not sure i would say that this is Le Guin's fault. it's probably my fault, being an unpatriotic asshole who both loves and hates this crazy place, and who is in agreement regarding all the negative points - and the positive ones too (introduced fairly late in the novel by a Terran envoy). i am automatically sympathetic to all the points made about the ivory tower of education, hypocritical politicians, unncessary wars, the poisonous yet hidden class system, the demeaning of women, etc. still, despite my lack of enthusiasm about A-Io, this is also where some of the most wonderful writing occurs, and where some of the most mind-expanding concepts are described.where the novel really shines is in the depiction of the Ambiguous Utopia, Anarres. everything is not peachy-keen on this arid, sadly animal and grass-free desert world. the ideals that created Anarres are indeed admirable; it was awesome to see my own (and countless others') anarcho-socialist jerkoff fantasies about how perfect it would be if we were all truly able to share, all able to chip in to help each other, if materialism was seen as an abomination, if we were able to give up on ridiculous hierarchical structures, etc, etc, et al enacted in a fairly realistic way and in a very positive light. but of course this is an "Ambiguous" Utopia, so Le Guin also shows how basic, power-craving, territorial human nature will always surface... how cooperative, communal living can also stamp down the individual, how it can make being different seem like a threat... how other-hatin' tribalism is ultimately toxic, no matter the tribe, no matter the utopia, no matter if the tribe is an entire nation - or world. Le Guin makes a utopia, then she nearly unmakes it by unmasking all of its issues and ugliness... but she does not denounce it. i loved that. Le Guin and Shevek still see the beauty in this culture, in a place that is anti-materialist, anti-capitalist; their goal is to explore how such a system can truly be maintained - in a way that is genuine and that respects the invididual, a society that is continuously revolutionary. and the true enemies of revolution are complacency and stasis.a closing word and quick circle-back to the sophistication of Le Guin's writing: i loved how Shevek's Theory of Simultaneity was reflected within the book's structure and by the political and moral themes as well. an example:"But it's true, chronosophy does involve ethics. Because our sense of time involves our ability to separate cause and effect, means and end. The baby, agan, the animal, they don't see the difference between what they do now and what will happen because of it. They can't make a pulley, or promise. We can. Seeking the difference between now and not now, we can make the connection. And there morality enters in. Responsibility. To say that a good end will follow from a bad means is just like saying that if I pull a rope on this pulley it will lift the weight on that one. To break a promise is to deny the reality of the past; therefore it is to deny the hope of a real future. If time and reason are functions of each other, if we are creatures of time, then we had better know it, and try to make the best of it. To act responsibly."

Jeffrey

May 04, 2016

When I started this novel I was a little worried because the prose seemed clunky and I was having a hard time settling into the novel. After a few pages that all changed, either I adjusted to her writing style or the writing smoothed out. If you experience this, hang in there, it is well worth sticking with this book. I see some reviewers think of The Dispossessed as an anti-Ayn Rand book. I didn't come away with that impression at all. I thought LeGuin did an excellent job of showing the fallacies of capitalism and socialism. The reason that any system does not work is always because humans are all too human. Bureaucracy, consolidation of power, judgment, and inequality always start to wiggle their way into the social matrix regardless of the intent of the society. Shevek, the main character, talking about his home planet Anarres, a socialist framework society. "You see," he said, "what we're after is to remind ourselves that we didn't come to Anarres for safety, but for freedom. If we must all agree, all work together, we're no better than a machine. If an individual can't work in solidarity with his fellows, it's his duty to work alone. His duty and his right, We have been denying people that right. We've been saying, more and more often, you must work with the others, you must accept the rule of the majority. But any rule is tyranny. The duty of the individual is to accept no rule, to be the initiator of his own acts, to be responsible. Only if he does so will the society live, and change, and adapt, and survive. We are not subjects of a State founded upon law, but members of a society founded upon revolution. Revolution is our obligation: our hope of evolution." Pretty heady stuff. Actually Ayn Rand could have wrote that statement. People find themselves on what seems to be polar opposites of politics, Republican, Democrat, Socialist, Capitalist, but in actuality all of them have more in common than they would ever admit. We all want the same things that is, in my opinion, the most freedom possible and still sustain a safe society. The difference is what system do we use to achieve those ends. Whatever system that the majority chooses to follow will eventually start to devolve into a facsimile of the original intent. Sometimes revolution, as abhorrent as it is, can be the only solution to wipe away the weight of centuries of rules and regulations that continue to build a box around the individual with each passing generation. I am not an anarchist, but I understand how people become an anarchist. The book certainly made me think about my place in the universe and about the aspects of my culture that I accept as necessary truths that on further evaluations prove to be a product of our own brainwashing. Too many of the governing parts of our lives that we accept as necessary truths have never really been questioned and weighed in our own minds. Why do so many of us work for other people now when a generation ago so many of us owned our own businesses? Walmart, though not the only culprit, has had a huge negative impact on communities destroying what was once vibrant downtown areas and forcing so many small businesses to close that it actually changed the identity of small towns. We were complicit in this destruction. We valued cheap goods and convenience over service and diversity. The capitalist swing currently is towards big corporations and I can only hope that eventually the very things we lost will eventually be the things we most want again. So okay, I have to apologize for pontificating about subjects seemingly unrelated to The Dispossessed. This novel is about ideas and regardless of how shallow a dive you want to take on this novel you will find yourself thinking, invariably, about things you haven't given much thought to before.

Sean Barrs

February 27, 2022

“My world, my Earth, is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and gobbled and fought until there was nothing left, and then we died. We controlled neither appetite nor violence; we did not adapt. We destroyed ourselves. But we destroyed ourselves first. There are no forests left on my Earth.” The Dispossessed is a phenomenal novel and there are many important aspects of it that warrant a thorough discussion; however, the above quote really stood out to me and will become the focus of my review.It is important because it shows Le Guin’s preoccupation with ecological thought. And this is a constant theme through her work. The character in question has witnessed environmental collapse and understands exactly why it has happened; it has happened because there were no restrictions placed on appetite, indulgence, and violence. Resources became a commodity, and all the forests were destroyed. Humans did not adapt, learn or grow. They continued down their destructive path and it led to their demise. (I think she's trying to tell us something here, don't you?) Le Guin establishes this by demonstrating that humanity is doomed to fail because of the divisions we have. She portrays two worlds diametrically opposed in their values. Urras is the crux of consumerist and destructive capitalism, and Anarres is an anarchist utopia in which no government reigns and every person is born equal. The former is driven by ideas of wealth and expansion, the latter by ideas of socialism. And although the alternative appears attractive to each counterpart, both have their own limitations because they cannot quite be reached in their pure state. Shevek, the protagonist and a brilliant physicist, comes to terms with the unattainableness of true freedom due to the fickleness of human nature: it is an impossible goal. He, the only man to witness the limitations of both political ideologies, understands that neither are enough to save or to benefit humankind by themselves. The ideology of Annares and its emphasis on universal survival, through altruism, is certainly the most attractive to me (and to him), but its system is the easiest to exploit by the corrupt minded. This idea, for example: “We don’t count relatives much; we are all relatives, you see.” This is a great concept because it extends the notion of family to every single person. Blood does not matter. Relation does not matter as we should look out for every single person regardless of our connection to them. This basic notion is innate and a moral principle for those born on Anarres. It is a simple requirement of society and it is there to ensure the survival of humanity. Everybody is here together, and they should work together. The ideology pushes universal altruism over individual aggrandisement, but if one deviates from this there are no repercussions. Trust is the key, but not everyone is trustworthy in life. And this is where the story begins to become complex. The freedom discussed here pertains to the notion of individual expression and argument. Both planets believe that their system is best and will benefit human advancement if all embraced it. They close themselves off. They close their minds off. Shevek, as a scientist, wants his idea to benefit all. It’s not about political ideology: it’s about benefiting humans, all humans, as a whole and not taking sides. The undercurrent of ecological concerns articulates this perfectly: we're all in this together and we must adapt, change and grow together so that we do not spoil our planet(s). We must not destroy our own humanity first because if we do then we will destroy our world, our forest. Two years later, these ecological concepts would be expanded upon in the equally as phenomenal The Word for World is Forest (note the title and its link with the quote here.) And it's after reading these two works that I consider Ursula K. Le Guin not only one of my favourite novelists, but also one of the most important writers of the late twentieth century. __________________________________You can connect with me on social media via My Linktree.__________________________________

Matthias

February 10, 2017

More than two months have passed since I've closed this book. While my traditional reviewing habit was one of immediately rushing to the closest laptop after reading the last line and sharing my excitement or the lack thereof in some hopefully original way, I felt a need to really let Le Guin's words sink fully into my mind and make them my own. (Actually, I've mostly just been very lazy in the reviewing department lately, but "letting words sink in" just sounds a little better.) But when it comes to making words my own, as this dear author evoked so well in this book, longing for possession is mostly futile, and so it is with ideas, impressions and most of all, inspiration. At least in my case good ideas tend to go and come as they please and if I'm lucky they can be grasped when there's something close at hand to write them down, just as the motivation and energy to write has chosen to quickly pass through my hands. Currently, the energy is there, but apart from some sparse notes that I now have to re-interpret myself, I only have a few central take-aways that I would like to share. This review can thus be considered as a barrel of some of the reflections I managed to retain before they too evaporated into untranslatable little figments of thought. The first take-away is that this is one of my favorite books. It is engaging, it is exciting, it teaches and it entertains. Le Guin's prose is nothing short of wonderful. While the plot is not exactly extraordinary, it provides the perfect mobile in which to transport some important messages on life and civilization that this author has chosen to share. The second take-away is that this is the best dissection of our society that I've read. I've read great books on the nature of human individuals on the one hand, and abstract philosophical meanderings on time and infinity, but never felt warm to the idea of reading about one of the levels that are in-between, namely society and civilisation. The reason why I never did is that there often seems so much more stuff wrong with society than right, so that it's hard to know where to begin complaining, and even harder to know where to stop complaining and inspire change. The building is showing so many signs of decay it's hard to dispel the idea to just throw it down and start all over. Ursula Le Guin found a great starting spot in this book with which to make a nice filet out of our civilisation: the idea of possession. The need of people to "own" stands central in our way of life, and the illusion of ownership pervades much of our thinking and doing. I myself am not immune. To give just one example, I prefer to buy books rather than to go borrow them at libraries. To give another example: I just bought an apartment. Now it would be unfair to point the finger just at people here. Animals do it too, on a certain level. They want to own territory, but instead of throwing money around, they urinate all over the place or emit certain smells. For all the faults our society has, I'm glad we evolved away out of that particular habit, if only for the sake of still readable books. Do I own these books because I gave money for them and they will soon by surrounded by MY walls? I guess so. Until a fire or a flood consumes them, until the hand of time consumes me. Yet, even though the banality of ownership during our short lives is inescapable, our ways of living are so much focused on exactly that futility it's no surprise so many people feel unhappy and wronged when they see their mission to that end either obstructed or sabotaged by those around them, or recognise their endeavors as futile once the mission seems largely fulfilled.This is just a personal take-away of course, because if Ursuala Le Guin is doing one thing exceptionally well, it is the convincing way in which she gives each perspective on the matter a stage in this book. I can easily see the staunchest proponents op capitalism (and as someone who profits of that system's fruits it would be hypocritical and outright dishonest of me to claim that I dislike it myself) like this book as much as a dirty hippy or clean-shaven commie. Possession isn't just about capitalism and material goods. It's more pervasive than that. Just think about how people refer to each other. "My" son. "My" girlfriend. "My" mother. Or how Jason Mraz chose to sing of his undying love by proclaiming "I'm yours". It's innocent most of the time, but when there's problems in relationships of any kind, quite often it is a question of a certain dominance, where one is under the other, where one is partly of the other. We like to own but we don't like to be owned. Except for Jason Mraz, that is. While writing this review I was faced with another example of the futility of possession. I had made notes while reading this book that I intended to use to inspire this review. There are some interesting one-liners, some runaway thoughts, some links to real-life experiences. I would call them "my" notes. But what the two month span between writing them and reading them has shown is that even my thoughts are not entirely my own. Some lines I wrote down there are now perfectly incomprehensible to me. Others I can give an interpretation, but without the guarantee it will be the same as intended back in the day. How are these alien words still my notes? "The Dispossessed" touches on many more themes than the one I evoked here, and Le Guin shows her genius on basically every page with throwaway wisdoms that pack a punch: on prisons, on the education system, on laws, on the press, on the world of art, the army, the list goes on. She can seem cold and pessimistic sometimes: "Life is a fight, and the strongest wins. All civilization does is hide the blood and cover up the hate with pretty words." or when she states that suffering, unlike love, is real because the former ALWAYS hits the mark. Despite this recurring pessimism, I found this book to be widely uplifting by looking through that veil of coldness and finding there the beauty of life, of all the things that transcend possession. Her criticism has an inherent warmth and is not above criticism itself. It's a criticism that has channeled my own apathy towards many of society's ways into something that seems more helpful: an understanding and even a renewed love. Yes, you read that right. I love society. There's nothing I'd rather live right next to.

Tadiana ✩Night Owl☽

June 28, 2019

4, maybe 4.5 stars. This classic SF novel kept me glued to my chair the whole time I was reading it. Granted, I was on a cross-country airplane flight from Washington DC to Utah, but still! It's very thought-provoking SF, set in the same universe as Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness, but even more politically inclined. Almost 200 years earlier, a group of rebels left a highly capitalistic society on the planet Urras, to form their more utopian government on the moon Annares. Now a man named Shevek, a physicist from this voluntary communistic society, leaves his barren world, where life is difficult but - mostly - fair, to go to the neighboring planet to work with the physicists there. Life on Urras is much more pleasant and luxurious, but gradually Shevek comes to realize the dark underside of that capitalistic society. The question is, can he escape the bind he's gotten himself into?The Dispossessed is one of the earlier examples of dual timeline storytelling in the SF genre, the chapters alternate between flashbacks of Shevek's life on his home world of Annares and his current experiences on Urras with the "propertarians" (heh). The Dispossessed thoughtfully examines the best and worst in these two political systems. Though Le Guin's choice of the better society is clear, it's laudable that she realistically handles how even good intentions can go awry because of human weaknesses like selfishness, fear and pride. Some might find this novel slow going, but if you're interested in contrasting political and social systems, I'd highly recommend it!Even though this novel is 4th in the Hainish Cycle, it's actually first chronologically, for reasons that become apparent late in the novel (and are somewhat spoilerish, so I won't get into them here). :)

Darwin8u

May 01, 2018

“You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution.” — Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed. Ursula K. Le Guin's 'The Dispossessed' represents the high orbit of what SF can do. Science Fiction is best, most lasting, most literate, when it is using its conventional form(s) to explore not space but us. When the vehicle of SF is used to ask big questions that are easier bent with binary planets, with grand theories of time and space, etc., we are able to better understand both the limits and the horizons of our species. The great SF writers (Asimov, Vonnegut, Heinlein, Dick, Bradbury, etc) have been able to explore political, economic, social, and cultural questions/possibilities using the future, time, and the wide-openness of space. Ursula K. Le Guin belongs firmly in the pantheon of great social SF writers. She will be read far into the future -- not because her writing reflects the future, but because it captures the now so perfectly.

Bradley

November 14, 2017

The first time I read this book back in the early nineties, I would have given it a four star rating because I was slightly annoyed with the prose and the steadily boring pace where nothing really big happens (mostly) except a general living of a life. This is despite our following a very interesting character escaping his pragmatic moon to gift his very advanced physics that would lead to not only an ansible for faster-than-light communications but also faster-than-light travel.The world-building is pretty amazing on both the political and socio-economic levels, the discussion of what men and women are to each other and just how amazingly different (and similar) it is between both worlds. The novel easily tackles six different heavy themes and does it with heart and no hammer in sight.On one hand, I know the author couldn't have tackled the whole gamut of two worlds without a very light touch, but it was this same light touch and frustrating lack of progress, the descent of the sense of utopia into desperate and dire dystopia, that eventually made me distrust this novel.It frankly took me two hundred pages, the first time, to even get into the novel. It requires a learning curve.Now that I'm reading this as a full adult with a lot of ideas under his belt, I eased into the read much more, expecting certain things and realizing it was primarily a novel of ideas and deep commentary. It's not just a political mirror or even a mirror between true communist idealism and anarchism. It's also a damn unique exploration of sexuality and how sexuality necessitates certain kinds of thinking, how a social structure informs it and how it can kill a real germination of ideas. I'm talking about two halves making a whole here. Men and women are just a half of it. The two political makeups of the moon and the planet aren't whole until they finally find a mix. It's Taoism and a mix of opposites and equals creating something more than the sum of its parts.And that's what is so tragic about this novel. There's distrust, revulsion against new thought, a nearly impossible wall between the sexes (and the obvious exception to that rule in this novel is noteworthy also because it occurs with the Dispossessed scientist). If people opened up their minds to new ideas, so much of this would have been avoided.During my original take, I was going to college at the time and I saw a lot of the same approbations and stifled thought in the academic arena. The Dispossessed brings up the plight of ourselves in science, the fact that certain ideas get heavily entrenched and new ones are mercilessly cut down at least until a new generation takes over.It all comes back to a germination of ideas. The call in the text to keep the flow of information going was really breathtaking, if not that unique. I think of the internet and how that has been such a boon to science now, but even in '92 when I read this, the weight of bureaucracy was immense. I'm sure things aren't all that different now. Aren't we still enamored with string theory and colliders and aren't we all getting rather upset that it hasn't been panning out as we would have liked? Well, alas, this isn't the forum for that but this book makes very good points all over the place.I ramble.The fact is, I'm increasing my rating on this book merely because it is gorgeous in conception and form. It carries on multiple narratives on so many aspects of our lives here and now and also within the fictional boundaries of political systems that don't exist anywhere except in our minds. She even goes on to conceive a world without cause and effect, where all things can and will be explored at the same time. How often can we have a cogent discussion about that, rooted firmly in the events of normal lives, and yet not have the text explode in handwavium and weird science? She keeps things real. And brilliant.I'm going to ignore my stylistic complaints and even the fact that I couldn't really get into it for hundreds of pages because the trip is more than impressive by the end. It's more of a monument to thought.

Brad

March 05, 2020

As a semi-retired actor, there are many literary characters I'd love to play, and for all kinds of reasons. Cardinal Richelieu and D'Artagnan spring immediately to mind, but there are countless others: Isaac Dan der Grimnebulin (Perdido Street Station), Oedipus, Holmes or Watson (I'd take either), Captain Jack Aubrey (I'd rather Stephen Maturin, but I look like Jack), Heathcliff, Lady Macbeth (yep, I meant her), Lady Bracknell (nee Brancaster), Manfred, Indiana Jones. But none of them are people who I would actually like to be.That I reserve for Shevek.Ursula K. LeGuin's Odonian-Anarchist physicist is what I aspire to be in the deepest places of myself -- flaws and all. The reason is simple and profound. Shevek constantly strives for change inside and outside himself, for an embracing of true freedom with the knowledge that freedom requires change, that change is dangerous, and that the danger of true freedom trumps safety. No matter what pressures are brought to bear, Shevek is his own man.I could go on about him, but I am loathe to diminish the strength of what I have written. So I will close with this: Shevek is the character I most admire in literature, and The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia is very nearly a perfect book.You must read it.After reading it again: I know more completely than ever that I am not Shevek, as much as I wish I could be, but this time through I realized that I do appear in the pages of The Dispossessed, or I think I've found the character most like myself even if we are not exactly the same -- Tirin. Tirin is the friend of Shevek's who debates hard questions with him when then are children/teens; he is the friend who drives the prison experiment after the travelling teacher comes through their town and talks to them about incarceration; he is the playwright whose satire so offends his brethren, then he suffers deep and hurtful criticism for his work; he is the man who is ostracized through exploitation of the Anarresti system, pushing him into terrible work details and isolation until he feels mad enough to check himself into a hospital; he is destroyed by that experience and spends the rest of his life stuck rewriting that one offensive, satirical play, trying to get it "right," obsessed with that one creation that he felt so strongly about and suffered so deeply because of.My personal trajectory isn't his -- no, not by a long shot -- but my trajectory does share similarities. I think, though, that what I have exactly in common with Tirin is his Quixotic fixation on what Leguin, quoting Marx, calls "permanent revolution," yet in Tirin's case that revolution is a revolution of the mind. A constant overthrowing of what is known to then reknow or relearn or reform as he creates and destroys with his art. And I do know his isolation. That I know very well. It was sobering to see myself in a devastated figure in a book I love. I don't wish it upon anyone: least of all you my kind reader.

Gabrielle

February 26, 2020

Updated review after a re-read in November 2019.---“Change is freedom, change is life.""It's always easier not to think for oneself. Find a nice safe hierarchy and settle in. Don't make changes, don't risk disapproval, don't upset your syndics. It's always easiest to let yourself be governed.""There's a point, around age twenty, when you have to choose whether to be like everybody else the rest of your life, or to make a virtue of your peculiarities.""Those who build walls are their own prisoners. I'm going to go fulfill my proper function in the social organism. I'm going to go unbuild walls.” This novel will for ever be one of my favorite books: when graceful, intelligent prose and brave, nuanced ideas collide into one great story that intertwines the personal and the political, you get a treasure like “The Dispossessed”. This book jumped at the top of my favorites list mere seconds after I finished the last line.Shevek was born and raised on the anarchist colony of Anarres, and while he has always embraced the principles on which his society was founded, as his work in physics becomes more complicated, challenging and promising, he begins to see cracks in the utopic system his ancestors created. A visit to the twin (but capitalist) planet Urras brings into sharp relief the differences between the two worlds, but also brings to light more commonalities than Shevek had expected. He soon finds himself caught in a high stake political game that would seek to make him the figurehead of a new revolution – or let him take the fall for its failure, depending on who has the upper hand.LeGuin built her story carefully, and the two narratives, one set on Urras and one on Annarres, feed each other and collide at the perfect moment to bring the story together flawlessly. Brilliant narrative structure aside, this book is simply stuffed with beautiful and thought-provoking passages I had to stop and re-read a few times.It would be a gross over-simplification to say that this is a sci-fi book about communism. Yes, it is that, but it is so much more. It is a nuanced, idealistic, heartbreaking, gentle and extremely intelligent novel. The subtitle “Ambiguous Utopia” is perfect: a book like that challenges the reader without ever trying to preach to them, letting them make their own minds up about the fictional anarcho-communist planet of Annares and its relation to its capitalist home world of Urras.Shevek is one of the most beautifully rendered characters I’ve encountered. Stuck between both worlds, he struggles with the philosophies he lived his whole life by, the advantages of the new world he is discovering and his longing for what he left behind. He is flawed and lost, but also incredibly wise and brave, with a strong sense of compassion and integrity. I just loved him. And unexpectedly, I found his relationship with his partner Takver to be deeply romantic.Le Guin definitely preached to the choir in terms of politics with me, I admit it. But I admired the fearlessness with which she chose to point out that whatever system of wealth distribution you live in, people will try to exploit each other, people will bully and ostracize those who don’t fit quite right with their herd, people will feel jealously and hatred. People on Annares share the wealth and the work, but they are still humans, with all the good and negative connotations that entails. This is why her utopia is ambiguous: human nature remains no matter what system you place it in and while you can dream of giving people a better life by giving them a system or code to get rid of inequalities, you can never remove the wild card of “people and how they will behave” from the equation.I believe this book to be a classic, and I believe it completely transcends the science-fiction label. It is nothing less than a great work of art in my eyes and I recommend it to everyone."You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit or it is nowhere."

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.