Recommended by 3 experts

The Rational Optimist Audiobook Summary

“A delightful and fascinating book filled with insight and wit, which will make you think twice and cheer up.” — Steven Pinker

In a bold and provocative interpretation of economic history, Matt Ridley, the New York Times-bestselling author of Genome and The Red Queen, makes the case for an economics of hope, arguing that the benefits of commerce, technology, innovation, and change–what Ridley calls cultural evolution–will inevitably increase human prosperity. Fans of the works of Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs, and Steel), Niall Ferguson (The Ascent of Money), and Thomas Friedman (The World Is Flat) will find much to ponder and enjoy in The Rational Optimist.

For two hundred years the pessimists have dominated public discourse, insisting that things will soon be getting much worse. But in fact, life is getting better–and at an accelerating rate. Food availability, income, and life span are up; disease, child mortality, and violence are down all across the globe. Africa is following Asia out of poverty; the Internet, the mobile phone, and container shipping are enriching people’s lives as never before.

An astute, refreshing, and revelatory work that covers the entire sweep of human history–from the Stone Age to the Internet–The Rational Optimist will change your way of thinking about the world for the better.

Other Top Audiobooks

The Rational Optimist Audiobook Narrator

L.J. Ganser is the narrator of The Rational Optimist audiobook that was written by Matt Ridley

Matt Ridley is the author of books that have sold well over a million copies in 32 languages: THE RED QUEEN, THE ORIGINS OF VIRTUE, GENOME, NATURE VIA NURTURE, FRANCIS CRICK, THE RATIONAL OPTIMIST, THE EVOLUTION OF EVERYTHING, and HOW INNOVATION WORKS. In his bestseller GENOME and in his biography of Francis Crick, he showed an ability to translate the details of genomic discoveries into understandable and exciting stories. During the current pandemic, he has written essays for the Wall Street Journal and The Spectator about the origin and genomics of the virus. His most recent WSJ piece appeared on January 16, 2021. He is a member of the House of Lords in the UK.

About the Author(s) of The Rational Optimist

Matt Ridley is the author of The Rational Optimist

More From the Same

- Author : Matt Ridley

- The Red Queen

- The Evolution of Everything

- Viral

- Genome

- How Innovation Works

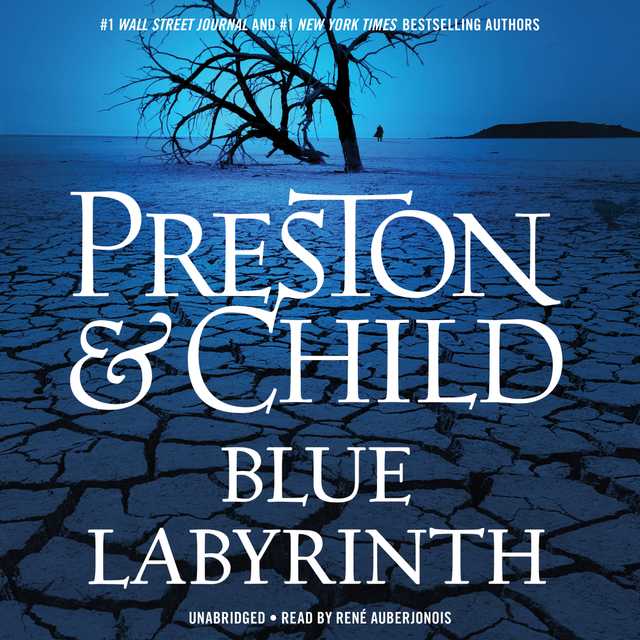

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

The Rational Optimist Full Details

| Narrator | L.J. Ganser |

| Length | 13 hours 38 minutes |

| Author | Matt Ridley |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | May 18, 2010 |

| ISBN | 9780061997655 |

Additional info

The publisher of the The Rational Optimist is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780061997655.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

The Rational Optimist is recommended by

Mark Zuckerberg

Mark Zuckerberg is a business magnate & philanthropist.

Argues [that] economic progress is the greater force [that] is pushing society forward.

Naval Ravikant

Naval Ravikant is an Indian-American entrepreneur and investor.

The most brilliant and enlightening book I've read in years.

Jordan Peterson

Jordan Peterson is a psychologist, author, & media commentator.

Recommends this book

Goodreads Reviews

Daniel

October 06, 2011

I just finished Rational Optimist by Matt Ridley. Because I am an overly pessimistic individual, I expected to hate the book.I loved the book.I should point out where I read the book, because context is important in this case. I was in Berlin. My hotel room was about 50 meters away from Checkpoint Charlie the central point of the cold war. I was within 2 minutes the remains of a train station where thousands of Jews were sent to their death. I was near the remains of the Berlin wall built to prevent people from escaping communists. Berlin could easily be the mecca of pessimists.Ridley is a very specific optimist: he believes that innovation is an almost unstoppable force. Food and energy shortages? We will invent new ways to produce more food and energy than we need. Effectively, human beings have become better at almost everything: producing goods and food, taking care of each other, learning, sharing and so on.But he is also a pessimist: he believes that if we stop innovation, we suffer. We must constantly out-innovate our problems. We will soon run out of food, energy and breathable air if we keep doing the same thing at a greater scale. Only by inventing drastically better technologies and organizations can we hope to prosper. Innovation is required for our survival. Civilizations eventually collapse, when they become unable to innovate around their problems.But where does innovation comes from? Ridley believes it comes from trade, taken in the broadest sense of the term. Traders are people who carry ideas from people to people. They are like bees in that they allow ideas to have sex… Traders allow people to specialize and to focus on perfecting ideas. Without trade, we would all need to be self-sufficient. Condemned to self-sufficiency, we would not have time to improve our methods nor share our ideas. Interdependency makes human beings better.How do you get more innovation? Do you have your governments entice researchers like myself to pursue “strategic” research? Absolutely not. Governments cannot create innovation. Instead, they should limit the wealth they extract from the economy by remaining small. Other institutions like banks should also be kept in check. In effect, central planning, wherever it comes from, should be avoided as it stops innovation in its tracks.Hence, civilization comes in as a result of trade, because it can siphon the newly generated wealth. It wasn’t the Jewish traders in the 1930s who drained the wealth out of Germany. With their various enterprises, they were the source of much of the wealth that the state was extracting. They were not the parasites.Ridley does not have much faith in science as a source of innovation. Most innovations comes through tinkering and trading ideas. Science and law come after the fact to codify what was learned. In effect, science may support innovations and inventions, but it is not the causal agent. What you want is trade and the freedom it brings. I share his vision. After all, Russians had top-notch scientists, but they were still unable to innovate in most fields.He sees a cycle, where innovation creates value which is then captured and killed by bureaucrats or obsolete corporations. But innovation always reappears elsewhere. He believes that the best place to be right now is on the Web. One day, governments and corporations will kill Web-based innovations, but by then, a new frontier will have opened.Ridley predicts the fall of corporations and the rise of bottom-up economics where individuals freely assemble to create value. Apple, Google and Facebook will soon collapse, faster than comparable companies a century ago.This book also explains why Germany is at least marginally richer than the United Kingdom even though the United Kingdom won the two last great wars and Germany lost. Winning is overrated. Wealth cannot be put into boxes and piled up. Had you confiscated all the computers from 1970s, you would hold a collection hardly more valuable than a single iPad.(Original text on my blog: http://lemire.me/blog/archives/2011/1...)

Steve

September 18, 2016

Another Goodreads member, Helen Grant, wrote a scathing review of The Rational Optimist:http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/...I found it particularly offensive and hypocritical that she took Ridley to task for his tone, calling it “blithe and pompous” in the midst of a review which was itself sarcastic, insulting, smugly self-congratulatory, and just plain vulgar. Certainly, Ridley can be sarcastic, and I consider that a blemish on his otherwise excellent writing. However, if Grant is going to criticize Ridley for his incivility, then it hardly seems appropriate for her to pungently describe the author as “full of shit”, and to insult his readers as ignorant.She began by writing about “biodiversity”, but oddly, she confused that issue with the issue of genetic engineering. The dangers of monoculture are so well-known that she need not have explained them in such tedious and inarticulate detail. What is more important is that she sought to equate genetic engineering (hereafter, GE) with monoculture, when, in fact, they are completely separate issues. I am bewildered by her attempt to equate the two. The practice of monoculture precedes GE by many decades, and is based on economics, not on biology. Furthermore, humanity is already sadly dependent on a very small number of staple crops. This is an important problem in its own right, but again, it is an issue entirely unrelated to, and long-predating GE.GE does nothing to compel monoculture, and there is no logical reason that it ought to reduce biodiversity. Furthermore, seed-banking and other methods of conserving a diversity of germ-plasm ought to be part of any wise approach to long-term management of our agricultural heritage. No one with any detailed understanding of biology, certainly not Dr. Ridley, who holds a doctorate in zoology from Oxford, would advocate that we rely on a hand-full of crops, and let our heritage cultivars disappear. Furthermore, the greater efficiency of GE crops, by increasing yields, would potentially allow us to reduce the number of acres under cultivation, releasing marginal land to return to the wild, and therefore fostering biodiversity.Grant wrote that “You can be a cautious optimist...” But, to advocate caution, or any other virtue, is meaningless without some fine-grained detail. What kind of caution? How much caution? What is missing from her advocacy of caution is any admission that excessive caution, is, in itself, dangerous. Yes, we want to be wise in our adoption of new technology. However, to err always on the side of caution is not an example of wisdom. Rather, it is a certain recipe for stasis, at a time when we have billions of people living in desperate poverty, and even outright starvation. Grant complained that Ridley’s examples were poor, but she gave no examples, herself, so I’m left without purchase to know how to respond with any specificity. I can only say that this reader, at least, found his examples wonderfully illustrative. To take only one, I loved his describing the cost of an hour of reading light through the ages, quantified, quite handily, in terms of the amount of labor at an average wage needed to purchase this commodity that we take so much for granted. To wit: Currently: less than half a second, using a compact fluorescent bulb1950: eight seconds, using a conventional incandescent bulb1880s: fifteen minutes, using a kerosene lamp1800s: over six hours, using a tallow candle1750 BC: more than fifty hours, using a sesame-oil lamp in BabylonFrankly, I found this example beautiful in its simplicity, importance, and relevance. He could have given us some high-tech example, but instead, he chose simple reading light, an essential of every day life. The profound importance of this example stuck me through the heart, as one who cares deeply about the third-world poor. As I say, we westerners take ubiquitous and inexpensive light for granted, but we should not. How many of the world’s poor still have no affordable source of light? Nightfall means bedtime for them. Can you imagine how confining this is? We, in the west, have no conception. If you are a poor, third-world parent, and you achingly yearn for your children to get an education, so as to have a better life, then pray, how is that possible without light? You cannot afford lamps or candles, much less a solar array. Finally, in her discussion of the Klebsiella planticola issue, Grant took a position that has long been thoroughly discredited. The mere fact that she still referred to the organism in question by its old name, eleven years after its genus was reclassified as Raoultella, is telling. She represented this as a case of a near world-ending biological catastrophe, in which very a dangerous GE organism, Klebsiella planticola, was nearly released commercially. Fortunately, according to anti-GE mythology, a champion arose, one Elaine Ingham, a professor at Oregon State University, a school well-known for its agricultural programs. She and her graduate student, Michael Holmes, cowrote and published some original research in 1999 on the organism in this paper:"Effects of Klebsiella planticola SDF20 on soil biota and wheat growth in sandy soil" Applied Soil Ecology 11 (1999) 67-78Dr. Ingham testified before the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Genetic Modification of New Zealand on behalf of a the Green Party of Aotearoa in February of 2001 regarding this research. For this, she was hailed as a heroine by anti-GE activists. Some of those political partisans went on to wildly exaggerate the facts, to claim that K. planticola could propagate promiscuously in the natural environment, and that its ability to produce ethanol could destroy every living thing on earth. Ingham, and the Green Party, itself, subsequently issued retractions and apologies to the Royal Commission, admitting that in her conclusions, Ingham had gone well beyond what the data actually showed. She had also cited a paper that did not exist, and had said some things that quite simply were not true. Specifically, the organism had not cleared regulatory testing, and was not on the verge of being commercially released. Yet, here we are, more than a decade after Ingham admitted that these things were not true, and we still find people such as Grant repeating them as if they are important, damning facts in an ongoing controversy. Shortly after she issued this written apology, 2001, Ingham resigned from her academic position at OSU. Some sources say that she was forced to do so. Rather predictably, when one reads the analysis of this aftermath by "greens", this event only enhanced Ingham’s role as a heroine to the movement, elevating her to the status of martyr. They characterize her resignation as something engineered by agribusiness companies, because they say that her truth-telling had threatened their bottom lines. One can only marvel at the workings of the conspiratorial mind. This skeptical reviewer suspects that there is a far simpler and more believable explanation. That is, the university forced her out because she had brought embarrassment on them as an institution, and she had ruined her professional reputation.In the interest of full disclosure, I do not work in the field of genetic engineering, nor do I have any financial interest in agribusiness. Politically, I am a liberal Democrat, not a Libertarian. I’m an ardent environmentalist, and an avid home gardener of heirloom varieties. I grow heirloom varieties for historical nostalgia, and for flavor, not because I fear GE varieties. I never stop to worry whether the tortilla chips that I buy at the local store contain GE cornmeal. Of course they do. Almost all Americans eat GE foods, almost daily, without a single, documented case of harm.I take it as a given that we will always see paranoid conspiracy theories, as well as frank hostility to science and rationality, on the political right, where it takes the form of such things as a belief in creationism. However, I'm sad to see similarly dangerous anti-intellectual nonsense coming from the left. I am deeply dismayed to find virulent, irrational opposition to wonderfully useful technology, such as vaccines and genetic engineering, coming from the ostensibly progressive end of the political spectrum. These tools are essential to solving pressing issues that I care about even more passionately than the environment. That is to say, poverty, hunger, and disease.I will close by recommending Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Discipline for his discussion of GE. He is a Stanford-trained ecologist, best known for founding and editing The Whole Earth Catalog. Science is by far our sharpest tool. Let’s use it. As Ridley, himself, wrote: "I am certainly not saying, ‘Don't worry, be happy.’ Rather, I'm saying, ‘Don't despair, be ambitious.’ " One thing that struck me again and again in this book, beyond any polemics, is Ridley's heartfelt commitment to solving the issues of hunger, poverty, and the environment. He spends much of the book explaining how this can be done. Yes, he is often abrasive in his expression of his political opinions, I will grant you. However, his heart is very much in the right place. Here's Ridley speaking about the book at Long Now, introduced by Stewart Brand:http://fora.tv/2011/03/22/Matt_Ridley...

A Man Called Ove

June 09, 2018

“I have observed that not the man who hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs when others hope, is admired by a large class of persons as a sage.” - JOHN STUART MILLAnd to make up for it, I will be generous and rate it 5/5. This is a slightly counter-intuitive book that argues for a bright, prosperous future of humanity despite climate change, despite clueless politicians, despite human nature itself and ofcourse despite the Left-liberals :) And religious radicalism doesnt even get a mention so theres a lot of work to do guys.According to the author there has been a tradition of prediciting armageddon - famines, global wars, acid rain and now climate change since the invention of the printing press. And each time, the pessimists have been proven wrong. The reason is that humans are blessed with the ability to innovate in ways that are impossible to predict. And a genuinely free market makes these possible.Another theme is that we humans have always imagined a better/perfect past. It should be painfully obvious that our lives much better - today than a century ago, in cities r rather than villages, with technology and markets rather than Thoreau/Gandhi’s self-sufficient and self-denying poverty.But more than all of the above, views on climate change were counter-intutive and seemed balanced. He is perhaps the second author (I have read) after Michael Crichton to question the mass hysteria around it. Really eager to read both sides of the topic now.Lastly, the book is lucid and a fast yet deeply satisfying read. And it is also short at 300 pages, compared atleast to Pinker’s Enlightenment Now which I have picked up on the same subject.

Douglas

March 12, 2017

Very valuable read overall. Apart from the secularism and the evolutionary assumptions, Ridley does a great job of describing things in a way that counteracts the very common and insistent cultural pessimistic narrative. Postmillenialists need to read this kind of stuff together with their scriptural studies. Eschatology, markets and progress all go together.

Jim

March 11, 2020

A much needed shot of optimism in the best of worlds (so far) that is drowning in pessimism. He discusses why in length toward the end of the book. He's an advocate of free trade & minimal government oversight, themes that run throughout this book. His overall point that the world is getting better all the time is well made. It's important & occasionally difficult to keep in mind that he's speaking to overall trends & populations as a whole.While he is persuasive & I generally agreed with him throughout the book, quite a few of his examples threw up flags in my mind. They seemed a bit too slick. For instance, his ideas of complete freedom of the markets are taken so far that he dismissed monopolies as being a problem that governments need to address. Indeed, it's the government monopolies that he fears the most. While he has a point, he took it too far & preached about it. I detest preaching, but he didn't descend into that very often nor for too long.Very well narrated & thoroughly interesting. Highly recommended, although I'd take some of his arguments with a grain of salt. Of course, I don't believe all the doomsayers either.Table of ContentsPrologue: When Ideas have Sex: Mixing it up with others in the world creates progress. Chapter One - A better today: the unprecedented present: The world is far better for most people today than ever before & Ridley has plenty of examples. We tend to lose track of that since bad news sells.Chapter Two - The collective brain: exchange and specialization after 200,000 years ago: Specialization isn't just for ants since many people can do what one can't. Our social learning & collective intelligence is unique.Chapter Three - The manufacture of virtue: barter, trust and rules after 50,000 years ago: was amazing. He says trade started a lot earlier than I or most previously thought & drove other developments such as farming & cities.Chapter Four - The feeding of the nine billion: farming after 10,000 years ago: I was familiar with quite a bit of this & really appreciated his thorough drubbing of organic farming. It's a terrible & ridiculous hoax. He mentions Borlaug & I'll recommend reading The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World for a better look. He correctly slams Greenpeace & others for keeping the poorest & hungriest from gaining access to GMOs.Chapter Five - The triumph of cities: trade after 5,000 years ago: A lot of good info, but he goes on his Libertarian kick again & simplifies the failure of nations as bureaucratic pillaging of trade economies. I think he takes it too far, but it is a good point to keep in mind.Chapter Six - Escaping Malthus’s trap: population after 1200: The idea of 'going back to the land' is a ridiculous idea today. There are too many mouths to feed & a city-dweller has a much smaller footprint than small rural farmers.Chapter Seven - The release of slaves: energy after 1700: From human labor to harnessing animals to using fossil fuels led to a staggering rise in our standard of living. It's no coincidence that slavery ended with the Industrial Revolution & he makes the point well. He also makes a great point for why we should love fossil fuels. Yes, we should replace them, but vilifying them is ridiculous. they've given us the portable power & materials to make the world the best it's ever been for us. He properly gives biofuels the drubbing they deserve.Chapter Eight - The invention of invention: increasing returns after 1800: It's incredible how much we've progressed in all areas over the past couple of centuries.Chapter Nine - Turning points: pessimism after 1900: Great examples of pessimistic prophecies that were often hilarious. He's quick to point out that they were generally right IF things had stayed the same, but they never do. Chapter Ten - The two great pessimisms of today: Africa and climate after 2010: The Africa section was really interesting. It's not something I've paid much attention to. I have with Climate Change & agree with him entirely. The current craze is getting out of hand & we need to be careful not to cut our own throats while trying to save our grandkids.Chapter Eleven - The catallaxy: rational optimism about 2100: An excellent wrap. He made his point well throughout the book, too.

Void

December 11, 2010

It's very rarely i stumble upon such a rare gem. I was initially a bit skeptical, thinking by the title it might be a blabla type feel good book, but i was blown away but i what I found: a very solid strong scientific book with tons of facts and reliable research. And while i did love feeling a biologist was explaining stuff, and it took me back to my old love of history (which i now see in a completely new light) what i was so very impressed to find was that it was written by a man who understands economics and society... Just mind blowing stuff. To name a few big thoughts that hit me in this book:- history not as seen through the "heroes" but as those people coming often just before the downfall of a civilization, the parasites that grew on the solid groundwork made by hard working people trading- society as bigger than the parts, because of trading- specialization is the reason we all have it so good today: people aren't smarter as individuals, but because they specialize they're smarter overall- a minimum population is required for any technology/culture to survive, otherwise it reverts to simpler states because it cannot susain specialization- I also love the section where he computes through time how many hours you'd have had to work to get the privilege of reading a book after sunset)- the limits of the planet are much bigger than scare people keep saying for many decades and centuries- many of the eco-friendly things proposed actually would hurt nature more, kill more people, while many counter intuitive economic development stuff will actually enable us to give more forest back to the planet- a lot of fascinating historical facts, about civilizations... the reasons for their rise and falls- all sorts of "ancient", "primitive" stories told with modern language... and u realize that some stuff in an ancient city were local branches of a big corporation, or thow historic figures are actually just the modern company boss trying to talk state into some monopolistic gains.- fascinating stuff, ancient temples functioning like banks in the money system, even a civilization in which the word for high preast is the same as that for accountant, as well as why first writing stuffwas trade related. Reasons why migrations occurred, differences between modern and old farmer as they moved towards Europe fertilizing lands by burning forests and then moving on... fascinating! - we are truly very privileged to live today. I was especially in love with the calculations of just how many slaves each of us has today because of availability of power (yes, even the word for electricity nails it), how in choices we're richer than kings, and in resources we have much more than any in the past... and most importantly, we are not rich in money but in the one thing that really matters: our time Can u tell i'm very excited about this book?!?!?

Maciej

May 07, 2019

As we are constantly bombarded with doom prophesies the book makes a really good job and puts all of that into greater perspective. Rational Optimist starts with a thesis that we are way better off than we ever were. The book states that our lives have improved significantly in terms of wealth, nutrition, life expectancy, literacy and many other measures. Matt Ridley makes convincing arguments that things will continue to improve. The book also serves as a defence of free trade and globalisation. We don’t need to agree with the Ridley theme of optimism for the future to make this book worthwhile to read. The book offers much more than the title suggests.The Rational Optimist seeks to explain how humans continuously managed to improve their quality of life. Honestly, after 1/3 of the book, I thought that its content will be exactly the same as one of my previous books... (if you like to read my full review please visit my blog: https://leadersarereaders.blog/the-ra...)

Gordon

April 08, 2011

Here is the central thesis of The Rational Optimist: What is uniquely human is that our intelligence is collective and cumulative in a way that is true of no other animal. (Richard Dawkins, of "The Selfish Gene" fame, dubbed the units of cultural imitation that comprise this heritage as "memes".) Evolution in sexually reproducing species is driven by genetic exchange. Culture evolution is much the same, but the unit of exchange is the idea. The truly Big Bang idea was that of division of labor, which was enabled by exchange itself. Once we start trading with each other, we can start specializing -- and as a result, we are all better off. And not just a little bit better off, but spectacularly better off.Side-note: This argument is reminiscent of V.S. Ramachandran's idea (The Tell-Tale Brain) that the critical "last" piece of evolution of the human brain that made possible the explosive rise of our species was the mirror neuron. By enabling us to communicate with one another and learn skills from one another through imitation, cultural evolution took over from genetic evolution as the driver of our very rapid progress over the last few tens of millennia.Ridley also makes the argument that greater trade / exchange correlates with higher wealth and income, and that in turn leads to higher levels of happiness. He rejects the idea of some saturation point beyond which increases in material well-being lead to no increase in happiness -- this saturation point being the key idea of the "Easterlin Paradox", named after its discoverer. I suspect that what is going on here may at least as much related to the fact that higher levels of development are typically accompanied by higher levels of equality (the US being a notable exception), but Ridley doesn't really consider that. As he points out: Never before this generation has the average person been able to afford to have somebody else prepare his meals." I think the message here is: eat up and stop whining.Ridley explains "exchange" as a giant leap beyond the ancient ploy of "you scratch my back I'll scratch yours". He says: "Barter -- the simultaneous exchange of different objects -- was itself a human breakthrough, perhaps the chef thing that led to the ecologic dominance and burgeoning material prosperity of the species." The simultaneous trading of different kinds of goods and services is very different from "You scratch my back now, I'll scratch your back later". The former implies specialization of labor, the latter does not.And then there's the innovation effect: "Without trade, innovation just does not happen. Exchange is to technology as sex is to evolution. It stimulates novelty." This also leads to an interesting analysis of why some isolated societies actually regressed. For example, when Tasmania became an island as a result of rising seas, the local population actually lost technology over the generations. There just wasn't enough critical mass to support the kind of specialized tool-making skills that were once possible, nor was there the ability to trade with other societies that did have such skills. Population crashes can also have such effects, especially if the population crash happens in an isolated population. Likewise, when the barbarian invasions of the Roman Empire in the 5th century put an end to secure long-distance trade networks based on Roman roads, technology and wealth very quickly began to go backwards. No more Roman baths. No more delicacies from far-off corners of the Empire. No more grain trade.One truly intriguing notion Ridley proposes is that human virtue and exchange are correlated. As he puts it, "History is driven by the evolution of rules and tools." The more market-oriented a society and the more it is trade-based, the greater the effort to be fair and to maintain a reputation for fairness. Otherwise, no one wants to trade with you. It you think of the rampant criminality in places like Russia and Congo, this thesis makes a lot of sense. True, there's a lot of unethical behavior on Wall Street, but not even hedge fund managers arrange to have their competitors gunned down on the streets or tossed into dungeons, nor do they generally rape and pillage (speaking literally, not metaphorically).And then there's agriculture. Ridley stands the usual notion of the role of agriculture on its head. Rather than arguing that it was agricultural surpluses that drove trade, he says it was trade that drove agriculture. After all, if you can't trade your surplus for other stuff, why bother growing more than you need?Ridley provides a quick summary of the effect of technology innovation on agricultural yields, from synthetic fertilizers to the tractor (which freed up 1/3 of agricultural land, which otherwise would have been used to feed draft horses) to genetically modified seeds. Not surprisingly, he has a lot of contempt for Greenpeace and other environmentalists who campaign against GMO. As with agriculture, Ridley also believes that the growth of cities was driven by trade. Exchange is much easier among specialists if they live close to each other. Similarly, when farmers bring their produce to market, they want to have a choice of many buyers for their goods -- and many other products that they can in turn acquire. Cities are very convenient places to do this. And as he points out, the planet hit a critical crossover point in 2008: for the first time in history, the majority of the world's population now lives in cities. Ridley has clearly been very much influenced by urbanization thinkers such as Harvard economics professor Edward Glaeser (skyscrapers drive civilization) and futurologist Stewart Brand (living in a slum is a lot better than living in the countryside).Continuing to turn conventional ideas on their head, Ridley moves on to science: he argues that it is not science that drives technology, it's mostly technology that drives science. In other words, people come up with pragmatic technology solutions that work, and then others look for the science that underlies those technologies. I think this is overstating the case, but there's the germ of a good idea here about the mutually reinforcing interplay between technology and science.From this idea about technology and science, Ridley leaps to the conclusion that we have been freed from the constraints of diminishing returns to scale. These constraints, so obvious to economist thinkers of the 18th C and 19th C like Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo and Adam Smith, have changed. The critical capital in post-industrial societies is not physical capital, but intellectual capital. Increasingly, industrial firms in the developed countries do less and less of their own manufacturing, outsourcing it to China and other emerging market countries so that they can focus on R&D, marketing, and other areas where they can add more value. Intellectual capital, much more than physical capital, can offer increasing returns to scale. It's not manufacturing economies of scale that power the growth of companies such as Apple, Facebook, Goldman Sachs, Google or Novartis, it's their intellectual capital: their brands, their patents, their business methods, their software. Their physical assets are almost trivial in relation to these. Malthus in particular -- and Malthusian ways of thinking about limits to growth -- come in for strong attack by Ridley. Malthus famously thought that we would breed ourselves into starvation. At various times, major parts of the earth's population have done so. But this is increasingly rare, as more countries go through the "demographic transition", whereby they reach a certain stage of economic growth and urbanization, and then birth rates begin to plummet. Several factors contribute to this: improved access to medicine causes infant mortality to drop sharply; life expectancy rises; children become more of a liability than an asset for urbanites; higher education levels make more women aware of contraception; women enter the paid workforce -- and then stop making babies. The Chinese example notwithstanding, coercive measures are not needed to speed this transition. It happens anyway. In future, the problem in all but the least developed countries will become one of too few babies rather than too many.One of the most insightful chapters of Ridley's book is the one on slavery and energy. He argues that slavery made sense only in the context of highly labor-intensive, low productivity economic activities such as agriculture. But when industrialization took hold and urbanization took off along with it, agriculture became mechanized. Machines were even cheaper than slaves, sharecroppers, serfs and other forms of low cost labor. But what powered those machines? A key enabling factor behind the industrial revolution was the increasing exploitation of fossil fuels, especially coal (with oil coming along a century or so later). Countries such as England had rapidly begun to bump up against the limits of exploiting water power, wood fuels and peat. These resources dwindled quickly, and rapidly rose in cost. Not so with coal, whose price for the most part has fallen steadily for over two centuries. Goodbye slavery.Of course, in all of the foregoing, there was no mention of the carrying capacity of the earth's environment as a constraint on growth. In truth, Ridley doesn't really believe in it. He thinks we'll come up with yet another clever innovation that will overcome such limits. Global warming? Not to worry. We'll think of something before too much longer. It's a touching belief, a true leap of faith in fact, but potentially fatal if wrong. It is this failure to consider the near-certain effects within this century of climate change -- rising temperatures, rising sea levels , rising ocean acidification, accompanied by major shifts in rainfall and increases in extreme weather events -- that is the single most glaring weakness of Ridley's book. I think he got so carried away by optimism that he veered from its rational form to its irrational form. I believe Ridley's failure to appreciate the importance of climate change is largely based on his emotional and ideological aversion to strong governments. If a strong government role is required to lead the fight on climate change, then he wants to pretend climate change isn't important. He doesn't seem to understand the role of government very well, particularly democratic government in developed countries, and focuses instead on the obvious weaknesses of dysfunctional autocratic government in failing countries. Yet it seems curious that the wealthiest countries of the world are precisely those that have strong democratic governments and well-functioning public sectors -- with perhaps the partial exception of the United States. However, the US has benefited extraordinarily from importing educated labor from abroad, from exploiting abundant resources in a large continent, and from living beyond its means as the holder of the world's only major reserve currency. There are limits to growth in that model too.All in all, this is a book well worth reading. It's thought-provoking, intellectually wide-ranging, mostly well-argued and … definitely optimistic.

David

November 10, 2011

Pessimists get all the media coverage; optimists are poo-pooed for their naivete. Nevertheless, Matt Ridley puts together a good argument that in general, conditions in the world are improving. Not everywhere, of course; but in general, living conditions are improving, there is less violence, innovation is accelerating, and the dire events predicted by doomsayers are not coming true.Free trade, cheap energy, and specialization are the things that help grow civilizations. Science is not the cause of, but a by-product of innovation. Innovation is the result of new ideas "having sex" with each other. These and many other interesting concepts are explained in this book, and make it very enjoyable.

Giovanni

November 09, 2019

Excelente. Mas certamente odiado por pessimistas, ecologistas apocalípticos e anti-liberais em geral. Por isso tantas avaliações negativas, politicamente motivadas. O livro continua robusto, baseado em dados, evidências e lógica.

Joachim

November 11, 2012

A truly inspiring book that goes against everything I've ever heard about the future of humanity.Ridley takes the reader on a journey from the beginnings of mankind through the present to our future as a species. The prognosis: A) We have much to be thankful for today, and B) the future may not be as bleak as we believe, in spite of climate change and other impending problems.Here's the gist: over time, humanity has managed to capitalize on specialization, trade and the cross-breeding of ideas (surprisingly well described using the metaphor of sexual promiscuity) to reach an almost unbelievable standard of living and high-speed adaptation. We have proven time and again, at every major impasse, that we are capable of dealing with the problems we create and the limits we run up against.Moreover, the crises that await us over the next century are not insurmountable. Our current forecasts make the same mistake that fortune tellers have made since the dawn of humankind - we always tend to see the future through the lens of our own times, without being able to imagine the opportunities that lie ahead, or the sweeping changes that will inevitably take place as we find new ideas and technologies that will drastically change the portrait. Moreover, in spite of all our challenges, we live in an age of unbelievable bottom-up innovation.Not only is the book beautifully written and thoroughly researched, but it has given me new hope for the future of the planet. We need fresh ideas, different viewpoints and off-the-wall dreamers in today's climate of rampant fear, paralyzing helplessness and cookie-cutter conformity.I can't help but put in my own two cents. I don't have as much faith in the invisible hand as Ridley does. However, I have to say that it was very refreshing to get a different look at things (I'm usually one of those Chomsky/Klein readers). As a wise man said to me, the truth about our future probably lies somewhere between Ridley's infectious optimism and Gore's stark prophecy.Hats off!

Gogelescu

September 11, 2021

“Not inventing, and not adopting new ideas, can itself be both dangerous and immoral.”

Shawn

December 29, 2018

This has been on my to-read list for a long time (originally it came out in 2010). I enjoy Ridley’s work, and this fits in well. There are few surprises for those who have read Ridley or similar books. Essentially: forget the day-to-day news cycle, look at the big historical picture and the data, and human life in general has been getting better and better; and there’s every reason to think it will continue to do so. But what about….Ridley probably discusses it and has an answer. Technology, wealth, ingenuity have and will continue to help us find ways to deal with problems and (and the new problems that arise from those solutions).What makes Rational Optimist somewhat unique is Ridley’s basic argument for why humans are able to succeed: where the technology, wealth, and ingenuity comes from. Combining, as he says Adam Smith and Charles Darwin, Ridley argues that what makes the human species unique and able to prosper so well is the sex of ideas. That is, the human propensity to exchange goods also leads to exchange of ideas. This, he argues, is the root of the existence of and expansion of cultural and collective knowledge. Ideas evolve (Darwin) through interaction (Smith). Through specialization, trade, and the evolution of ideas, humans are able to adapt and achieve ever higher standards of living. It is a fascinating thesis, and Ridley explains it in detail, going through history and pre-history to find evidence for it. The audiobook is well-produced and keeps your attention. I tend to lose focus somewhat with numbers and statistics, so the print version would be good if that is important.

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.