Why Bob Dylan Matters Audiobook Summary

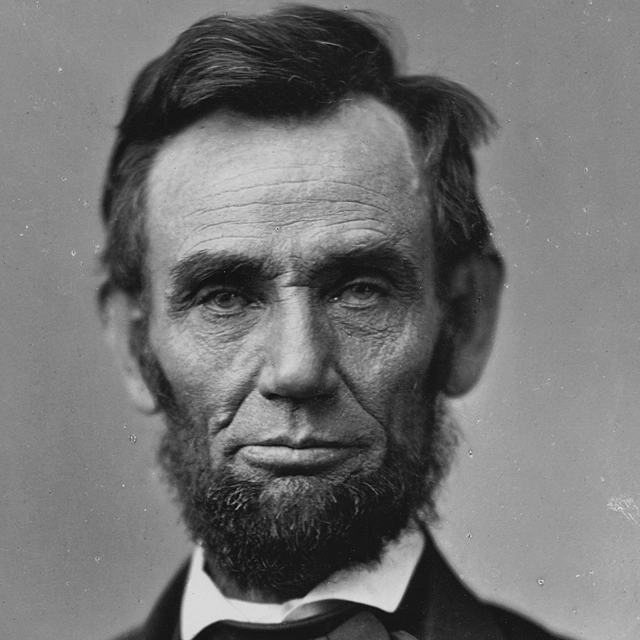

When the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Bob Dylan in 2016, a debate raged. Some celebrated, while many others questioned the choice. How could the world’s most prestigious book prize be awarded to a famously cantankerous singer-songwriter who wouldn’t even deign to attend the medal ceremony?

In Why Bob Dylan Matters, Harvard Professor Richard F. Thomas answers this question with magisterial erudition. A world expert on Classical poetry, Thomas was initially ridiculed by his colleagues for teaching a course on Bob Dylan alongside his traditional seminars on Homer, Virgil, and Ovid. Dylan’s Nobel Prize brought him vindication, and he immediately found himself thrust into the spotlight as a leading academic voice in all matters Dylanological. Today, through his wildly popular Dylan seminar–affectionately dubbed “Dylan 101”–Thomas is introducing a new generation of fans and scholars to the revered bard’s work.

This witty, personal volume is a distillation of Thomas’s famous course, and makes a compelling case for moving Dylan out of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and into the pantheon of Classical poets. Asking us to reflect on the question, “What makes a classic?”, Thomas offers an eloquent argument for Dylan’s modern relevance, while interpreting and decoding Dylan’s lyrics for listeners. The most original and compelling volume on Dylan in decades, Why Bob Dylan Matters will illuminate Dylan’s work for the Dylan neophyte and the seasoned fanatic alike. You’ll never think about Bob Dylan in the same way again.

Other Top Audiobooks

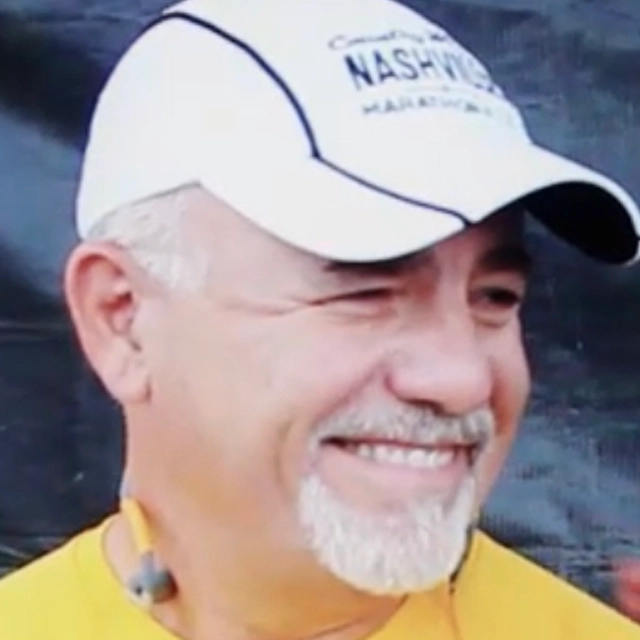

Why Bob Dylan Matters Audiobook Narrator

Nick Landrum is the narrator of Why Bob Dylan Matters audiobook that was written by Richard F. Thomas

Richard F. Thomas is George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University, a Bob Dylan expert, and the creator for a freshman seminar at Harvard on Bob Dylan.

About the Author(s) of Why Bob Dylan Matters

Richard F. Thomas is the author of Why Bob Dylan Matters

More From the Same

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

Why Bob Dylan Matters Full Details

| Narrator | Nick Landrum |

| Length | 9 hours 14 minutes |

| Author | Richard F. Thomas |

| Category | |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | November 21, 2017 |

| ISBN | 9780062695000 |

Subjects

The publisher of the Why Bob Dylan Matters is HarperAudio. includes the following subjects: The BISAC Subject Code is Biography & Autobiography, Composers & Musicians

Additional info

The publisher of the Why Bob Dylan Matters is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780062695000.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

Jess

May 13, 2018

The author is a mega fan of Dylan and teacher of his music philosophy. I’ve been a Dylan fan since high school and never really paid any mind to his lyrics. This book was a great, almost scientific, account of Dylan’s lyrics, what they’re based on, the truths and impressions behind them and how they reflected the times which Dylan represents. In essence, Dylan’s work is further testament that history repeats itself. I wasn’t surprised to learn that Dylan, as a famous icon, did not enjoy fame like other icons do. He is an artist through and through and I think that’s part of what makes his music and lyrics so influential.

M.

November 17, 2017

https://msarki.tumblr.com/post/167583...Of all the many books regarding the life and work of Bob Dylan this one ranks at the top when it comes to being scholarly. Part of a long-standing Harvard class taught by Thomas, this distillation dissects no few examples of Dylan’s now-classic role in producing great works by stealing from others. More importantly, however, Bob Dylan makes what he steals his own. No small task and something only a very few distinctive artists can pull of successfully. But the great ones in fact do exactly that. What interests me most is Dylan’s process of creation based on the studies, experience, and knowledge of the professor’s obsession with great Classic art. It is no stretch to state that Dylan is one of the best in the business and well-deserving of his 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Bernie

March 06, 2020

Obviously, in the annals of popular music, the work of Bob Dylan matters. To make sense of the title and related objective of this book (which might otherwise seem presumptuous and demeaning) one has to know a little about some recent history of the politics of the Nobel Prize for Literature. (No, not the internal scandal that delayed the issuance of the 2018 Prize to 2019.) In 2016, an American hadn’t won since 1993 (Toni Morrison,) and given the relative volume of publications from America this was coming to be seen as a major “screw you” to the nation’s literary community. The Nobel committee claimed it was because American authors didn’t get their works translated and were too insular with respect to the global literary community. Still, the disparity was on the minds of many. Then, Bob Dylan was issued the Prize. While some who were offended by this disparity were placated, many thought it was an even bigger “screw you” than if the Committee again hadn’t issued it to an American – like it was a “you asked for it, you got it; now shut up for at least the next 15 years!” kind of award. I doubt anyone would deny that, as a pop music lyricist, Bob Dylan is brilliant – if not the best -- but for many that still just made him a middling poet. (Dylan wrote one piece of prose poetry, “Tarantula” as well as “memoirs” [that were apparently largely an act of creative writing,] but only his lyrics could feasibly merit issue of the award.)It was with that mess in mind that Thomas delivers this book. It seems to be his objective to not just prove that Dylan matters -- generally speaking -- but that Dylan’s work matters as literature – presumably, such that he’s at least as deserving of the Nobel Prize as any living American poet, story-writer, or novelist. The thrust of Thomas’s approach is in showing that Dylan’s work is dialed into the global literary canon. As a classicist, Thomas puts particular emphasis on Dylan’s stealing from, and referencing of, Greek and Roman figures like Homer and Ovid. (I mean "stealing" only in the sense that word used by artists, and there is considerable discussion of that subject, herein.) However, he does also show how Dylan uses and references other poets from Shakespeare to an obscure Confederate poet. So, the logical question is whether Thomas answers his book’s titular question with enough authority to convince the reader that Dylan does matter. Thomas certainly convinces us why Dylan matters enough to have classes taught about him, like the one Thomas teaches a Harvard. However, I can’t say that I was convinced that Dylan is on-par with… for instance, Cormac McCarthy or Salman Rushdie (who resides in the US, as I understand it) as a major literary figure. While Thomas does show that Dylan’s work is literature because Dylan’s work is wrapped up in literature, the only real argument he offers for whether Dylan is at the highest echelon of literature is his intense fan-boy devotion. We see a lot of comments like: “He had all that he needed to write ‘Masters of War,’ the greatest anti-war song ever written.” Not “one of the best,” not “the best, in my opinion,” not “the best rock-n-roll anti-war song,” but a gratuitous presumption that nothing else could be considered in the running enough for there to be a debate. Thomas’s enthusiasm that Dylan is among the biggest artistic geniuses of our time – if not all time – is certainly potent, but not necessarily compelling. The book is annotated, has a bibliography and a graphic discography.I enjoyed this book. I learned a lot about the works of Bob Dylan and I found the author’s fervor for Dylan’s songs contagious -- if not altogether convincing that it merits Dylan’s inclusion with Hemingway and Faulkner as an American literary icon. [Though I would not in the least challenge his inclusion as an icon of folk, rock, or pop music.] If you’re interested in Dylan, or this question of whether he’s the best American for the job of Literary Nobel Laureate, this book is worth a read.

Steve

December 17, 2017

Why Bob Dylan Matters is an important, but flawed "study" of Dylan and his lyrics. Given the relative shortness of the book (358 pages, notes and all), and the length of Dylan's career, that would seem, on surface, to be impossible. But Harvard Classics Professor Richard Thomas, a Dylan enthusiast who has been teaching a class on Dylan since 2004, has applied his academic eye and ear to Dylan's lyrics, and has made some fascinating discoveries. The trigger appears to lie in the discovery that Dylan (as young Bob Zimmerman) took Latin in high school. Back in the 50s, there was nothing unusual in that, since Latin was by far the language most taught in schools. You might call it conventional. Young Bob Zimmerman liked it well enough to also be a member of the Latin Club for a few years. Thomas does a great job of providing a foundation for the importance of Dylan's high school learning in the preceding pages when he writes about how Dylan, upon receiving the gold medal for his Nobel, spending considerable time studying the medal, with its Muse and Lyre scene from the Aeneid. Thomas knows an artistic circle when he sees one.What follows are a number of song examinations and comparisons with Classic poets (Homer, Virgil, Catullus, Ovid) with, to my mind, concrete examples of where Dylan has used lines or themes from these poets to construct his own songs. Thomas calls these examples "intertexts" (haters will call it plagiarism). I have no problem with how Dylan constructs his songs, since there's little doubt in my mind that was he has constructed is new. The echoes, the fragments, etc, if discovered, just add to the richness of the song. T.S. Eliot would have approved. One example that kind of blew me away was the fairly recent "I Pay in Blood," from the Tempest album. That song, with its "I pay in blood, but not my own" line has puzzled me, but Thomas points to Homer, and Odysseys' bloody return home. Whoa! Bar the gates and bring me my bow. That song is frequently on Dylan's recent setlists. There are many such revelatory moments in Why Bob Dylan Matters, that I now have a long list of songs and albums to revisit. That said, around chapter 8 Thomas seems to slip into full Bob Love. The concerts are always "perfect," the singing is always "beautiful," every setlist, every gesture, every interview utterance, is pregnant with meaning. A little bit of this kind of adulation can go a long way, and Thomas gives you way more than a little. I will grant that Dylan's singing on the American standards albums (Triplicate) is definitely better than the alarming croaking on Tempest, but I attribute that change to either surgery and/or tossing the smokes. Still, Bob Love aside, Thomas makes a strong case for Dylan being a Classic (and a very well read one). If you thought Dylan was a genius before, Why Bob Dylan Matters just adds to the legend.

Robert

January 06, 2018

This book did it. It answered all my questions about Dylan as well as others I didn’t know to ask. It's an amazing book even though the title assumes its own answer. But my most recent question is ‘why was Bob Dylan selected as the 2016 Nobel Prize recipient for Literature?’ When the award was announced to the world, I immediately recalled the most recent American recipient, 23 overdue years ago, Toni Morrison back in 1993. Then, I thought of the first American recipient, Minnesota’s own Sinclair Lewis in1930, both esteemed novelists. Now MN has 2 and one is a poet! To his own surprise, Bob said that he had never thought his song lyrics were ‘literature,’ “but neither did Shakespeare,” he said. Dylan said, “both of us were too busy with more mundane matters about how to begin a song or a play; which musicians or actors would be best for this one?” But, the Nobel Committee declared that his writings “created new poetic expressions in the great American song tradition.” Tracing the truth and veracity of this claim is author Dr. Richard Thomas, a Harvard professor of Classical Literature. He’s a die-hard Dylan fan who has attended concerts here and abroad for decades. He even offers a Dylan course of study every other year to Harvard freshmen. This text is a condensing of those lectures. In this book he offers multiple, convincing answers to the title’s implied question filling not only the 323 pages of text but also includes nearly 100 footnotes (endnotes) regarding specific quotes, as well as a 50-source bibliography followed by 5 pages of citations for lyrics quoted from Dylan’s 38 albums. Plus, at the end, there’s a 17 page-long Index of references and cross-references. Holy Cow! Obviously, Thomas knows how to create and fulfill a thesis. Thomas’ book is worth reading only if you wonder why Dylan has been so revered throughout the past 6 decades. There’s more to him than meets the ear.

Jim

December 29, 2018

Everything He Could StealRichard T. Thomas book, Why Dylan Matters gives valuable insights into Bob Dylan’s art. Thomas is a professor of the classics at Harvard and explains Dylan’s relationship to Greek and Roman poets such as Ovid, Virgil and Homer. He defends the charges of plagiarism Dylan has

Terry

January 04, 2018

Richard F. Thomas, George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University, dylanologist and the creator of a course at Harvard on Bob Dylan, gives us an incredibly erudite analysis of Dylan's poetic genius and a thorough back-to-back with authors to the likes of Virgil, Homer and Ovid. Dylan's life-long obsession with Ancient Rome ("Going back to Rome / That's where I was born"), the transfiguration of himself into some other spirits belonging to other eras (Odysseus?) and the use of the intertextuality among other techniques, bring his magistral way of playing with words and nostalgia to a level beyond the question "Is this literature?" that was on everybody's mouth at the news of his winning of the highest prize for Literature, the Nobel in 2016. He's a master of songwriting and that's a fact, and, as mentioned above, he's a master of intertextuality, of borrowing, readapting, stealing, recreating and giving new life to words and melodies of the past, words known and words forgotten and now brought back to life. He's not a plagiarist, everything he takes he wants us to know from where. As T.S. Eliot said “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.”I have to admit I am a huge fan of Dylan's oeuvre, and definitely I had my reasons to believe Dylan mattered immensely even before the Nobel or before reading this book, but I have learnt a lot more about him and I would have surely enjoyed this long length essay even as a non-fan. I have also rediscovered curiosity towards some of the classic poets and I'm about to read Catullus and Rimbaud for the first time after more than a decade.

Floyd

July 04, 2018

This is an excellent book written by a Harvard University classicist, who traces Bob Dylan's master works to classic Roman poets and other historical literary figures. I have been a Dylan fan since High School and never really worried where his songs came from. I just knew that I loved the music. I think the following sentence from the introduction sums up Dylan's greatness: "Dylan's art has long enriched the lives of those who listen to his music, through a genius that captures the essence of what it means to be human." I think this book would be enjoyed by those who are not as particularly taken with Dylan as I am. In addition to his music's classical lineage, I enjoyed learning the "back story" of many of his more notable songs.

Peter

March 23, 2019

I've been a huge Bob Dylan fan since discovering his music in my early teen years thanks to the Forest Gump soundtrack my parents owned. I've spent hours listening to his music, thinking about his lyrics and trying to figure him out. This book was overflowing with useful and interesting tidbits about his life but the arguments about why he matters were not what I was hoping for. Basically the author says he matters because he is continuing on the tradition of the ancient Greek and Roman poets. That's all well and good but isn't what makes him great in my mind. One of the best parts of the book was a section about how many people are disappointed and even angry when they see him perform live because he doesn't match the Bob Dylan in their minds. When I saw him at the Eccles, I was livid but with the passage of time and with help from this book have come to understand the error of my ways and I actually look forward to seeing him again if the opportunity arises. This book is highly academic but a must read for any die hard fan. Now that this book is finished I need to go back and work my way through the 32 albums.

Richard

December 18, 2018

Well, ok, I've read an embarrassing number of books about the great Bob Dylan, good, bad, and stupid. This one links Bob with the likes of Homer, Ovid, Virgil, Milton, Rimbaud, and a number of lesser known lights. The key word here is "intertextuallity," a.k.a., stealing, but not - I repeat - not plagiarism. Fascinating, in a geeky sort of way. Necessary to nuts like me. There you have it.

Jane

November 07, 2019

Very interesting information about how the work of Bob Dylan is related to many poets.

Edwin

April 22, 2020

Dylan and TransfigurationIn a 2012 interview with Mikal Gilmore, Dylan says: "I went to a library in Rome and I found a book on transfiguration." This is one of the most interesting points in the book, as Dylan never makes it clear what transfiguration actually is. The dictionary definition of transfiguration reads:transfiguration: 1) The dazzling change in the appearance of Jesus when on a mountain with three of his disciples (Matthew: 17:1-8; Mark 9:2-8; Luke 9:28-36); a picture or representation of this. Also, the church festival commemorating this event, observed on 6 August. 2) The action of transfiguring or state of being transfigured; metamorphosis.Dylan tells Gilmore that he's been transfigured, but when asked what he means by transfiguration, Dylan is characteristically recalcitrant. Instead, he gets Gilmore to read some passages out of Ralph "Sonny" Barger's book--cowritten by Keith and Kent Zimmerman--Hell's Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club. The pages Dylan has Gilmore read concern the motorcycle death of a Bobby Zimmerman.The interesting thing is that Bob Dylan was born Bob Zimmerman. And like the Bobby Zimmerman of the book, Dylan too had a horrific motorcycle accident in Woodstock. A puzzled Gilmore then asks Dylan: "Are you saying that you really can't be known?" Dylan replies enigmatically:Nobody knows nothing [of course Dylan is a fan of the double negative]. Who knows who's been transfigured and who has not? Who knows? Maybe Aristotle? Maybe he was transfigured? I can't say. Maybe Julius Caesar was transfigured. I have no idea. Maybe Shakespeare. Maybe Dante. Maybe Napoleon. Maybe Churchill. You just never know because it doesn't figure into the history books. That's all I'm saying.Gilmore presses further, and, like Iago in the Shakespeare play, all Dylan says in response is: "I only know what I told you. You'll have to go and do the work yourself to find out what it's about."If I were to hazard a guess, Dylan has a powerful imagination. Most people, when they listen to a folk song, they don't hear or understand the words. They just like the music. Then they're those people who are more analytic. They hear and understand the words. On the next level up, there are the people like Thomas, Harvard professors who analyze the words and their meaning. Then there are the few who become part of the tradition. Their imaginations are so powerful, they enter and live out and are part of the songs they sing. Transfiguration, if I were to hazard a guess, is Dylan taking on the personae of the people and places he sings about. It's a process of metamorphosis.If you ask Dylan, he wasn't born in Minnesota. He was born in Rome. And he had the wrong parents. What is more, he wasn't born Bob Dylan. He was born Robert Zimmerman. One of his favourite lines from Rimbaud is: "Je est un autre" ("I is someone else"). In a Halloween performance, he tells the audience that he's wearing his Bob Dylan mask. He has a fluid personality that he reinvents. Perhaps "he" even is too concrete a word for a man who sings, in a song released a few weeks ago, that "I contain multitudes."When Dylan saw Buddy Holly a few days before the plane crash, he recalled that:Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn't know what. And it gave me the chills.Compare this to what Dylan said decades later in 1997, after the release of his comeback album Time out of Mind: "On some night when lightning strikes, the gift was given back to me and I knew it ... the essence was back." And then compare that to how he describes his songs as something "that has been there for thousands of years, sailing around in the mist, and one day I just tuned into it." There is no Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan is a conduit, a lightning rod for the Muse of song that sometimes comes to him and sometimes deserts him. When Dylan says "transfiguration," he means that the Muse has come to him, inspiring him to take on the spirit that once moved Homer, Virgil, Dante, Woody Guthrie, and the other singer of tales.The songs that Dylan sings have a life of their own. Through the centuries, they find different hosts: one time they would find expression through Ovid, another time through Dante. In these modern times, they speak through Dylan. When Dylan says he's transfigured, I take it to mean that he's taken on the persona through which the tradition can speak out. In the 60s he was the folk singer, the original hobo. In the 70s he became the rock star. In the 80s he became the preacher. In the 90s he went back to his storytelling roots. And most recently, he's been the mouthpiece of the Great American Songbook. Each time he changes, that's when he's transfigured and infused with a new jolt of energy just like that time when Buddy Holly zapped him in the 60s or in the 90s when lightning struck and the gift was given back.I say all this about transfiguration because I've experienced it as well, once. I was in my early twenties. I found a book about transfiguration. There actually is no such book. But there are books that can transfigure you, and I think that that's what happened to Dylan in Rome: he found a book he felt such an affinity towards it changed his life. The book that transfigured me was Homer's Iliad.I read the book in three days. Skipped out of my college classes. Didn't eat. Didn't sleep. Everything in it made sense to me. I grasped it all at once, and intuitively. Homer relates in the book how everything happens over and over, how the heroes duel again and again in an eerily similar sequence. I got it all: the power of fate, even over the gods. It all clicked: the fatalistic heroes who were caught in the hierarchical power of the heroic code, a zero-sum game. "When my time comes," they say, "I'll breathe my last. But until that time comes, I am." I was struck by the theodicy of the poem: we suffer to become a song for the singers of the future. I was transfigured, transported into a heroic world that had more sense than today's wild world.When we are transfigured, we enter into the world of literature or the world of the song. But there is no point explaining the experience of transfiguration to the non-believers. The non-believers will say we cannot experience what has happened so long ago: the long ago was stranger than we think. We can only experience what we thought it was like. But Dylan, I argue, would say different. At the end of the song "Duquesne Whistle," he tells us that we come back again and again in an eternal recurrence:The lights of my native land are glowin'I wonder if they'll know me next time aroundI wonder if that old oak tree's still standingThat old oak tree, the one we used to climb.I'll see you down the road, the next time you come around. It could be tomorrow or a thousand years from now. Homer, Achilles, Dylan, Catullus, and the Jack of Hearts are all incarnations of their underlying forms and archetypes. They have been, and will be, again and again, transfiguring and metamorphosing in an unbroken dance.Why Bob Dylan Matters"Why Classics matter" has been a rallying cry in Classics departments for some time now, so it's of little surprise that a classicist would call his book on Bob Dylan Why Bob Dylan Matters. In the words of Thomas:This is also a book about how Dylan's genius has long been informed by the worlds of ancient Greece and Rome, and why the classics of those days matter to him and should matter to all of us interested in the humanities. We live in a world and an age in which the humanities--the study of the best that the human mind has risen to in art, music, writing, and performance--are being asked to justify their existence, are losing funding, or are in danger of losing funding. At the same time, those arts seem more vital than ever in terms of what they can teach us about how to live meaningful lives.I've always been of two minds when I see the question framed in this way: "Why the Classics matter," "Why religion matters," "Why the humanities are important," and so on. In one way, I see that it's a natural question to ask, and one that will draw viewers. But in another way, I don't like the question, because it's asked from a standpoint of weakness. In ages where the Classics, religion, and the humanities were strong, no one would frame the question that way. Their importance would be axiomatic. No justification required. So the book title, while appealing in one way, is distasteful in another in that it presupposes that Bob Dylan--like the Classics, religion, and other institutions under fire of late--needed the help of academics. Bob Dylan is just doing fine.Painting Blood on the TracksThere isn't enough material on Bob Dylan's affinity with the Classics to fill an entire volume. Thomas gets around this by integrating his own growing fascination with Dylan over the years into the book's narrative. Thomas was born in 1950. Dylan, born in 1941, was nine years his senior, the right age to have influenced young Thomas. For example, Dylan's first original album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan would have come out when Thomas was thirteen. That's about the right age when your ears are alert for brave new songs to follow.Some of these non-Classical asides are gems. When talking about Dylan's 1975 album Blood on the Tracks, Thomas quotes Dylan giving props to a painting teacher he had found in New York in 1974:I was convinced I wasn't going to do anything else, and I had the good fortune to meet a man in New York City who taught me how to see. He put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt . . . when I started doing it the first album I made was Blood on the Tracks.To illustrate the principles of fine arts in songwriting, Thomas quotes the lyrics of "Simple Twist of Fate:"A saxophone someplace far off playedAs she was walkin' by the arcadeAs the light bust through a beat-up shade where he was wakin' upShe dropped a coin into the cup of a blind man at the gateAnd forgot about a simple twist of fate.The Hibbing High YearsDid you know Dylan, then called Robert Zimmerman, grew up in small town Minnesota? He was born in Duluth and grew up in Hibbing, where he attended Hibbing High. As you would expect, Thomas covers Dylan's membership in the Hibbing High Latin club as well as the escapist sword and sandal movies popular at this time. While Hibbing lacked many of the cultural perquisites of future world-historical figures, it gave Dylan two things: a performance venue at the Hibbing High auditorium--a gorgeous 1805 capacity facility where he would play with his band The Shadow Blasters--and a desire to get out. Dylan would later capture his boyhood memories in song:They all got out of here any way they couldThe cold rain can give you the shiversThey went down the Ohio, the Cumberland, the TennesseeAll the rest of them rebel rivers.The Mesabi iron range--one of the world's largest open pit mines--was a source of wealth in Minnesota, and one of the reasons why Hibbing High had such a grand auditorium. The mine must be awe-inspiring: it is also a topic in one of Springsteen's songs of desolation "Youngstown."Dylan and CatullusOne of Thomas' aims is to discuss not so much Dylan's direct allusions to the writers of antiquity but rather the techniques of storytelling Dylan uses that go back to the ancient writers. One of my favourite points of discussion was how the Roman poet Catullus and Dylan use similar techniques. Thomas compares, for example Catullus poem 11:You who are ready to try outwhatever the will of the gods will bringTake a brief message to my old girlfriendwords that she won't like.Let her live and be well with her three hundred lovers,Not really truly loving thembut screwing them again and again.to Dylan's "If You See Her, Say Hello:"If you see her, say hello, she might be in TangierShe left here last early spring, is livin' there, I hearSay for me that I'm alright though things get kind of slowShe might think that I've forgotten her, don't tell her it isn't so.From the 1st century BC to 1975, the poem is a messenger. The more things change the more they stay the same.Closing ThoughtsThe aim of the book was to connect Dylan with the pantheon of classical poets. One question the book left me with: does Harvard Classics professor Richard F. Thomas perhaps enjoy Dylan even more than the classical poets? Perhaps...There's more to Thomas' book than what I've described. He goes into Dylan's set lists, Dylan's affinity with the road-weary Greek hero Odysseus, and Dylan's Nobel Prize. This is a book that I'll be rereading down the road. Would that all books by Harvard professors were such a delight.

Ned

August 20, 2021

Contagious enthusiasm The author is certainly enthusiastic about his subject. I enjoyed this book and learned a lot about Dylan since I have really only a tangential knowledge of his work. I am a fan of some of his iconic songs but wouldn't consider myself a fan of the man and I am far from a "Dylanologist." The most attractive thing to me is Dylan's reserved nature, his unwillingness to publicly commit himself to popular "causes." In fact, the more popular the cause the more suspicious he becomes. That is such a rare quality as to be nearly unheard-of. No virtue signaling here. I think Dylan deserves his accolades for his deep and wide body of work and it was nice to acquaint myself more with his development as an artist. A man who won't be pigeonholed or bandwagoned is worthy of admiration for that reason alone.

Mark

May 21, 2019

I should qualify that I am a Bob Dylan fanatic. So, of course I picked up this little gem. Its accomplishments are many, the greatest of which, in terms of effect on the reader, is that I now long to be a Bob Dylan scholar. Fanaticism is no longer sufficient. And, as the author concludes using Dylan’s own lyrics, a book like this only begins to scratch the surface of Dylan’s oeuvre. I have dozens of notes and highlights to keep me in serious study of the man and his work for years to come. That makes the book invaluable. Thomas’ description of what intertextuality means and how Dylan used it to bring the poetic sensibilities of Homer, Ovid, and Virgil back into contemporary songwriting was masterful. It has unlocked the second half of Dylan’s work for me in ways I never imagined possible. My self-study of Dylan ended with Infidels, one of my favorite albums released coincidentally the year I was born. Why Bob Dylan Matters opens up his latest work, enmeshing Dylan’s unique brand of storytelling (stemming from the Rimbaud “I is another” notion of detachment) with the great storytellers of antiquity. Something Thomas didn’t account for, something I think obvious when he wonders—understandably so—if Dylan lead his acceptance speech by quipping about the moon because Seamus Heaney did the same thing in 1995. It’s the scope of Thomas’ search to explain every detail that makes the book both brilliant and mad. In the back of my mind, I kept my own personal philosophy I’ve developed about Dylan.I’ve heard Dylan once said he just chooses words that sound good to go next to each other. I don’t remember where I even heard it or so I can’t definitively say if Dylan ever said it, which makes it as true as anything in the book of Dylan. The person who said it refuted the fact. He said there was no way that that is how Dylan’s process works. But the more I study Dylan’s work and the shifting imagery he fronts as his process, the more I realize that it is precisely true.To intertextualize (in honor of Dylan) my own favorite poet, our creativity has two channels: an input and an output. Artist’s (I am including myself here as a writer) are always ingesting. Ingesting never ends. What we subject ourselves to is constantly being absorbed. It’s why Stephen King suggestions in his book On Writing that if you want to be writer, you should probably stop watching TV altogether. The output becomes the surfacing of whatever you can reach for that has been digested on the intake.I personally believe Dylan’s creative process is as simple as that: putting down words that sound good next to each other. In all of Thomas’ brilliant research and staggering connections, he does neglect that simple truth. When you care for nothing but your aesthetic, when you are aware that everything you read and watch will shape your own, what you produce is out of your control. It’s easy.

Peter

May 10, 2018

“Why Bob Dylan Matters,” by Richard F. Thomas (Dey St., 2017). This is what happens when a scholar of the classics, a full-on Harvard academician, gives Bob Dylan the complete, footnoted treatment. Thomas, who is the George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard, is also one of those guys who knows every note of every recording, unreleased recording, erased recording, misheard interview, of a musical figure---a fanatic, but charming. Thomas comes by this honestly, of course: he has been teaching a freshman seminar on Dylan for years. The book seems to have been stimulated by Dylan’s being awarded the Nobel Prize, as a full-on defense of him as a great literary figure. Thomas argues that Dylan’s lyrics over the decades are infused with erudition, with references if not quotations from Homer, Virgil, Ovid, and other ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as Dante and Shakespeare and…you get the picture. He subjects the words to line-by-line, and word-by-word exegesis. At times the book feels like a concordance. Dylan did not steal or plagiarize—he transformed. To document and support this, Thomas goes all the way back to Hibbing High School, where the then-Zimmerman was a member of the Latin club and was exposed to the classics, up to when Dave Van Ronk and other Village folkies introduced him to Verlaine and Rimbaud. He argues that Dylan, in his evolution and transformations, has been deeply engaged in classic expression of love, loss, memory, grief, etc. It all ends with a careful analysis of Dylan’s Nobel speech. Careful? The account of the ceremonials becomes cringingly hagiographic, with Dylan’s language brilliant and masterful. Umm, Bob didn’t go to the ceremony? He deals with that in three short sentences. He couldn’t see himself in that august room; it just wasn’t his thing. Right. Btw, this is all about the words; nothing at all about the music. I am being snide, but a lot of that is just envy. I had no idea Bob Dylan was so erudite and learned. Thomas never does say why it matters, though. https://www.harpercollins.com/9780062...

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.