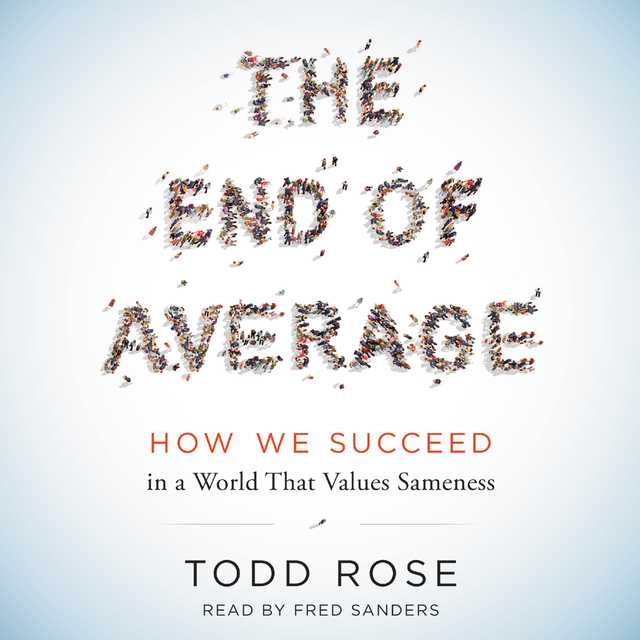

The End of Average Audiobook Summary

Are you above average? Is your child an A student? Is your employee an introvert or an extrovert? Every day we are measured against the yardstick of averages, judged according to how closely we come to it or how far we deviate from it.

The assumption that metrics comparing us to an average–like GPAs, personality test results, and performance review ratings–reveal something meaningful about our potential is so ingrained in our consciousness that we don’t even question it. That assumption, says Harvard’s Todd Rose, is spectacularly–and scientifically–wrong.

In The End of Average, Rose, a rising star in the new field of the science of the individual shows that no one is average. Not you. Not your kids. Not your employees. This isn’t hollow sloganeering–it’s a mathematical fact with enormous practical consequences. But while we know people learn and develop in distinctive ways, these unique patterns of behaviors are lost in our schools and businesses which have been designed around the mythical “average person.” This average-size-fits-all model ignores our differences and fails at recognizing talent. It’s time to change it.

Weaving science, history, and his personal experiences as a high school dropout, Rose offers a powerful alternative to understanding individuals through averages: the three principles of individuality. The jaggedness principle (talent is always jagged), the context principle (traits are a myth), and the pathways principle (we all walk the road less traveled) help us understand our true uniqueness–and that of others–and how to take full advantage of individuality to gain an edge in life.

Read this powerful manifesto in the ranks of Drive, Quiet, and Mindset–and you won’t see averages or talent in the same way again.

Other Top Audiobooks

The End of Average Audiobook Narrator

Fred Sanders is the narrator of The End of Average audiobook that was written by Todd Rose

About the Author(s) of The End of Average

Todd Rose is the author of The End of Average

More From the Same

- Author : Todd Rose

- Dark Horse

- Collective Illusions

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

The End of Average Full Details

| Narrator | Fred Sanders |

| Length | 6 hours 31 minutes |

| Author | Todd Rose |

| Category | |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | January 19, 2016 |

| ISBN | 9780062415806 |

Subjects

The publisher of the The End of Average is HarperAudio. includes the following subjects: The BISAC Subject Code is Psychology, Social Psychology

Additional info

The publisher of the The End of Average is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780062415806.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

Brian

January 23, 2016

Averages are very convenient when used correctly, but even when dealing with statistics they can be misleading (when Bill Gates walks into a room of people who have no savings, on average they're all millionaires) - and it gets even worse when we deal with jobs and education. As Todd Rose and Ogi Ogas make clear, hardly anyone is an average person. Whether someone is trying to devise an aircraft cockpit for the 'average' pilot, define the average kind of person to fit a job, or apply education suited to the average student, it all goes horribly wrong.If I'm honest, there isn't a huge amount of explicit science in the book (nor is it the kind of self-help book suggested by the subtitle 'how to succeed in a world that values sameness'), but scientific thinking underlies the analysis of how averaging people falls down, whether it's looking at brain performance or personality typing. What Rose and Ogas argue powerfully is that the way we run business and education is based on a fundamentally flawed concept that you can do the right thing for everyone by applying an averaged approach. This dates back to the likes of Galton, who believed that individuals had inherent capabilities and should be ranked and statistically managed accordingly.Along the way, the authors demolish such concepts I have seen time and again as: selecting for jobs on having a degree; performance management systems that require a fixed distribution of high performers, average people and below average people; companies based around organisation charts rather than individuals; and education that simply doesn't work for many students. I was particularly delighted to see the way that they pull apart the ridiculous approach of personality profiling with devastating statistics that show that the way we behave is hugely dependent on the combination of individual personality and context - hardly anyone is an introvert or judgemental or argumentative (or whatever you like) in every circumstance.The authors admit that the averaging approach was useful in pulling up a 19th century population that had few educational and job opportunities, but now, especially when we have the kind of systems and information we have, they argue that we should be moving beyond simple one-dimensional concepts like IQ and SAT scores and exam results and using multidimensional approaches that take in far more, and which enable us to build employment and education around the individual, rather than the system's idea of an average worker or student. Of course, there is more work involved that with the old averaging, but Rose and Ogas point out this benefits both the workers and the companies (or the educators and the educated). And they show that it is possible to take this approach even in apparently low wage, impersonal, cookie-cutter jobs like workers in a supermarket or manufacturing plant.There are a few issues. There's an out-and-out error where they claim the word 'statistics' comes from 'static values' (it actually comes from 'state', as in country). And even the authors occasionally slip back into the old norms of success when, for instance, they refer to 'Competency-based credentialing [is that really a word?] is being tried out - successfully - at leading universities.' Surely the concept of a 'leading university ' just reflects the old norms of what constitutes success in education? And I think the practical applications of these ideas will generally be a lot harder than they seem to think - they have great examples of where a low-level worker is given the chance to make a change that benefits the company, for instance, but not of what do when someone makes a change that makes things go horribly wrong. Similarly they point out that individual treatment also risks dangers like nepotism - but not how to deal with it. However, that doesn't in any way counter the essential nature of their argument. Individuals work and learn and do everything better if treated as... individuals.I really hope that those involved in business and education (and many other areas of public life) can get on top of this concept, as it could both transform the working experience of the majority and make all our lives better. I remember being horrified when consulting for a large company where pay rises were forced into a mathematical distribution - you had to have so many winners and so many losers, all based around an average performance. This kind of thing is becoming less common, but most businesses and education still has the rigid picture of averages and ranking that the authors demonstrate so lucidly is wrong and disastrous for human satisfaction. In reality, I suspect the changes won't come too widely in my lifetime. But I'd love to be pleasantly surprised. And I hope plenty of business people and academics read and learn from this book.

Seema

August 04, 2019

Everyone needs to read this book!

Mike

September 26, 2016

"Our one-size-fits-all world is actually one-size-fits-none." The concept of "average" was developed some two hundred years ago and now suffused most areas of our life--education, aptitude tests, jobs, performance reviews. Todd Rose argues that it is time for the science of the individual to come to scene, as it could bring better results. Instead of "aggregate then analyze" we should shift towards "analyze then aggregate" approach. The book resonates quite strongly with a lot of my work and I find it relevant and timely, providing good case studies.

Christopher

March 17, 2016

** spoiler alert ** Mr. Rose’s book could have been called, How We Came to Have Screwed-up Ideas, and What to Do About Them.Instead of building systems to fit the individual, organizations still try to fit people into systems. In the industrial revolution this made sense because uneducated farmworkers were needed for routine factory work. But today we have more functional and exciting options.What made sense to the father of scientific management, Frederick Winslow Taylor, now needs a rethink. Taylor was against innovation by workers. In his opinion, an employee’s job was to obey. Today, employers are crying out for people who can innovate. Because of institutional one-dimensional thinking, jobs go unfilled while able people aren’t considered for employment. Most organizations are what Mr. Rose disparagingly calls “averagarian.”How we became averageOur culture is built around averageness, an idea first introduced in the early nineteenth century by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer. Quetelet was trying to measure planetary speed. He came up with the then novel idea to find the average of variable astronomical observations in the belief that the result would be accurate. Astronomers thought the average of all the data points was the correct speed: deviation was error. The idea took hold. Average became sought-after perfection.Quetelet analyzed chest circumferences of 5,738 Scottish soldiers in his search for the average man. In the 1940s, researchers gathered data on ten anatomical dimensions of young men in the hope of finding the best cockpit design and then recruit pilots to fit in them.At the same time the search was on to find female perfection. Dr. Robert L Dickinson, Chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Brooklyn Hospital, was known as the “Rodin of Obstetrics.” Dr. Dickinson and his collaborators took physical measurements of 15,000 young adult women and created Norma, a sculpture that can be seen today in the Cleveland Health Museum.The trouble was that there were almost no pilots or young women who actually matched the (average) ideal. There was too much individual variation. Broad conclusions say almost nothing about individual experience and capacities.Mr. Rose cites how Sir Francis Galton agreed with Quetelet that the average was the basis of scientific understanding of people. Galton didn’t see average as perfection. He saw average as mediocre. For him deviation from the average wasn’t error but rank.Ranking is a prime attribute of one-dimensional thinking. It’s a perspective that permeates just about every aspect of life today: from medical dosages designed for the average patient, to ranking “likes” on Facebook.For Galton people were essentially eminent, mediocre or imbecilic. He divided these three categories further. And here’s where it gets whacky. According to Galton, if you’re mediocre, then you’re mediocre in every aspect of life. If you’re eminent, you are superior in every way. Sir Francis Galton was an upper-class chap living at the height of the British Empire. Could this have been self-serving stuff?Today, Galton’s thinking is no stranger to us. If Tiger Woods is a superior golfer then—according to popular opinion—he “should” be better in every other way. If you have excellent academic credentials you’ll be a better employee, perform well in anything you choose, live a happy life, and be admired by the less fortunate. We know this isn’t true. Yet it’s a widespread cultural blind spot.Making it humanStories make this book hard to put down. They’re well researched, and range from business to the military. But most compelling are those stories the author tells of his own struggle. When Mr. Rose was 18 he dropped out of high school with a D-minus average, and scratched a living at menial jobs. Today, he is director of the Mind, Brain, and Education program at Harvard.In high school he played the class clown so he wouldn’t be harassed by a group of boys. When he went to college, he purposely signed up for more classes than he intended to take. He wanted to avoid his old high school classmates. If they were in a class, he would drop it. His contextual criterion was adaptive, personal, and pragmatic. He wanted distraction-free study.In another instance, he tells of studying for the Graduate Record Examination, a requirement for science programs. He does well on verbal and math, but not “so-called” analytical reasoning. His father points out to him that he has poor working memory and that he should write down the problem. Awareness of our limitations opens possibilities for functional personal adaptation.Three principlesThe End of Average is organized into three principles: jaggedness, context, and pathway.JaggednessOver-simplifying leaves out necessary complexity. Average is one smooth number derived from varying (jagged) data points. Jaggedness restores accuracy as an individual signature. One graphic in the book shows a tall thin man and a short stout man. Both might weigh the same, but that’s about all you can say. Simplicity is the enemy of accuracy.Each individual is better adapted to some things and not to others. A person may be a nurturing mother, poor at economics, and a proficient computer programmer. The data points are a person’s individual jagged signature. And this has profound implications for business. Employee-hiring methods are fundamentally flawed.Relying on past achievements in college, grade point averages, and resumes come at a great cost to employers. Instead, Mr. Rose suggests focusing on what the company wants done. He goes on to show how innovative companies are finding loyal and enthusiastic talent where averagarian companies wouldn’t consider looking.ContextTrait theorists believe we’re either introvert or extrovert. But humans aren’t fixed entities. Nor are we disembodied abstractions. We’re influenced by situations we find ourselves in: context. Moreover, personalities aren’t consistent. What one person finds exciting, another finds anxiety provoking. Personal experience and behavior are linked to situation. The same individual is going to respond differently at an IRS audit than on the dance floor.Personality typing such as Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Enneagram don’t take situation variability into account. This might seem obvious. But as a culture we are still influenced by Galton’s fixed and simplistic categories, smart people and not-so-smart people, successful and not-so-successful.PathwayMr. Rose’s third principle is pathway. His own path wasn’t linear. While some occupations demand a rigid pathway, not all do. Not everyone who passes a bar examination goes through law school. You “just” need to pass the examination.And then there is the issue of pace. One-dimensional thinkers see only one right path and only one right speed. No matter what undergraduate degree you take, you have to take at least four years to achieve it. Success means clocking seat time and not failing “required” courses. An averagarian mindset limits individual potential.Mr. Rose advocates, not for diplomas, but short-term credentials and the ability to stack them. Some employers agree with him. An increasing number of innovative companies are throwing away the resume to make room for more functional hiring decisions. These are not based on average scores, but on contextual fit, individual interest, and capabilities.Technology can now manage complexity the individual approach demands. And not just in hiring. Technology-enhanced individualistic medicine is still in its infancy, but it’s growing. And on the education front, alternatives to the rigidity of alma mater (nurturing mother) are becoming a reality.There’s explosive growth in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) where learning is flexible and often free. Institutions, educators, and employers are missing something hidden in plain sight: the complex individual.Only when employers change hiring practices and look beyond diplomas and past employment will they discover they’ve been looking for talent in the wrong places. First employers need to change their thinking—no small task. But reading The End of Average by Todd Rose is a good start.Disclaimer: Christopher Richards is a business book ghostwriter and has no affiliation with this book or its author.

Sean

August 26, 2017

A book which ought to be read by anyone involved in standardised systems: teachers, managers, admissions officers, pretty much everyone. The solutions aren't easy, but they are definitely worth it.___The central premise of this book: No one is average. If you design a cockpit to fit the average pilot, you've designed it to fit NO ONE.Averages have their place. If you are comparing groups of people, the average can be useful.But the moment you need to make a decision about an individual (to teach this child or hire that person), the average is useless. In fact it is worse than useless, because it creates the illusion of knowledge while disguising what is most important about an individual.From the early 1900s, Francis Galton's idea that human worth could be measured by how far they were from the average had thoroughly infiltrated all social and behavioral sciences.Typing and ranking have become so elementary, natural and right that we are no longer conscious of the fact that every such judgment always erases the individuality of the person being judged. Frederick Taylor's Scientific Management put the system first, forcing individuals to conform to the average as closely as possible, or be like everyone else, only better.But standardisation left one crucial question unanswered: who should create the standards that governed a business? Thus the field of management was born. And management consulting followed soon after this separation of thinking and planning from making and doing. Its role? To tell businesses the best way to manage, employing the average as its key tool. SOPs and manuals ensued.Taylorism contributed to a relatively stable and prosperous democracy, at the cost of narrowing expectations of success, and losing our dignity of individuality.The fallacy of Quetelet and Lord and Novick: assuming that measuring one person many times and measuring many people one time were interchangeable. The three principles:1) Jaggedness: Jagged qualities consist of multiple dimensions that are weakly correlated. Height is one-dimensional, size is not. E.g. People can have widely differing waist sizes and shoulder widths, in different directions. There is no simple answer to the question: "Which man is bigger?"When we are able to appreciate the jaggedness of other people's talents - we are more likely to recognise their untapped potential. And when we become aware of our own jaggedness, we are less likely to fall prey to one-dimensional views of talent that limit what we are capable of.2) Myth of Traits: We behave similarly across time in similar contexts. When the context changes, our behaviour can also change. Fixed traits do not exist.Companies always lament a shortage of talent, that there's a skills gap, but really there's just a thinking gap. If you spend the effort thinking through the contextual details of the job, you're going to be rewarded.People's behaviour feels trait-like because you usually observe them in the same context, and when you observe them, YOU are part of that context. We simply do not see the diversity of contexts in the lives of our acquaintances or even those closest to us and, as a result, we make judgments about who they are based on limited information.Remembering that there is more to that person than the context that finds both of us together in that moment opens up the door for us to treat others with a deeper understanding and respect than essentialist thinking ever allows us to. And that understanding and respect are the foundation of the positive relationships that are most likely to lead to our success and happiness.3) We all walk our own paths. When learning skills (e.g. learning to walk), everyone has their own pathway to competence.Equating learning speed with learning ability is irrefutably wrong, yet pervades the education system when time limits are imposed on exam papers. By demanding that our students learn at one fixed pace, we are artificially impairing the ability of many to learn and succeed. What one person can learn, most can learn if they are allowed to adjust their pacing.From the author: When I consider the decisions I made that contributed to my college success, every one of them was rooted in the belief that a path to excellence was available to me, but I was the only one who would be able to figure out what the path looked like. And to do that, I knew that I needed to know who I was first (jaggedness, if-then signatures).When you take individuality seriously, innovation occurs everywhere, all the time, at every link of the network, because every employee is transformed into an independent agent tasked with figuring out the best way of doing her job and contributing to the company.The diploma as a basic unit of higher education has an unwieldy length (4 years), and is insufficiently granular. A better approach is credentials, which emphasises awarding credit for the smallest meaningful unit of learning. And this credit is pass/incomplete, assessing someone's competency at a given task.The present architecture of our higher education system is based on a false premise: that we need a standardised system to efficiently separate the talented from the untalented.Fit Creates Opportunity. If the environment is a bad match for our individuality - e.g. the cockpit doesn't fit the short pilot - our performance will always be artificially impaired.Opportunity has hitherto been defined as equal access, where it aims to maximise individual opportunity on average by ensuring equal access to the same standardised system, whether or not that system fits. But only equal fit creates equal opportunity.

Shivam

November 02, 2017

A few years back I decided that if I write a book in future, it's title would be "Being Average". And then I find this excellent book by Todd Rose. I wanted to write a book on being average to show the readers that there is nothing wrong in being average in anything or everything. But back then I was thinking about average only through few parameters which I had direct experience in. This book gave a very different outlook on how to understand averages and how the world adopted to Taylorist view of averaging everything.I find the structure of sentences sometimes complex which hinders the flow of reading, but it is extremely rich in content. The real power of the book comes when reader links the content with personal experiences.I would definitely recommend this book to all the students especially because it is the time when one compares his/her performance by comparing with that of others. I used to feel very bad about my performance in few courses in my Masters, about the structure of the course and how I lost a lot of time just to complete the mandatory courses. I wanted to select the courses which I wanted to study, but due to the rigidity of system, I had to go through them. But now when I understand how that model of education came into practice, I can get over it and do something to rectify it.

Oscar

February 12, 2022

I wish this platform gave two options for writing a comment. 1. what you think about the book or 2. what you learned about the book. Sometimes i’ll fall into the trap of reading a book tocheck mark it off, and that defies the purpose for me, but i feel like this platform in a way encourages that. I learned about the powerful shift in psychology from Adolphe Quetelet’s “Averagarian Thinking,” which makes up so much of our society today—i.e., comparing a student’s grade to the average, their SAT score to the average, a worker’s efficiency to the average, a worker’s average time it takes them to accomplish something… and you personally are either categorized as being below average or above average at that task. I had a 75% test average in Physics before my last test, and something like 85% for Chemistry. But I understand Physics on a level that is incomparably higher than I do chemistry. And chemistry is really just the physics of small particles…. With averagarian thinking, individual contexts are removed, and you might say that overall I have an X gpa, removing all these what statisticians might deem outliers. But they’re not outliers… i really don’t understand chemistry, and i really understand physics but tend to develop test anxiety with those problems or overcomplicate certain things or have a completely wrong approach to problem solving. Averages obfuscate those contexts. in this book, Todd Rose explains the shift from averagarian thinking to emphasizing individuality. This is powerfully summarized in the following quote: any system designed around the average person is doomed to fail. Rose justifies his belief about the importance of individuality through his emphasis on three main principles: the jaggedness principles, the contextness principle, and the pathways principle. in short:jaggedness principle - illustrates that there’s so much variability in humans. there’s no such thing as the average brain or the average body dimensions or the average hand size. if you take a 400 pound man, he might be above average in weight, but below average in most other dimensions, like reach, chest size, leg length, etc, and thus would he be considered average when taking all those body dimensions by an equal weighting system to someone that’s below average in weight, etc. but above average in height and reach. They’re incomparable, and averages don’t work in these contexts.that lead to principle two.contextness principle - explains that the behavior of people and certain patterns is heavily depend r on the contexts that they’re in. Ex: MBTI myers briggs test says i’m 60% introverted. in chem class im like 90% introverted but in math class or even english, im probably more extroverted. Averages make the picture less clear. someone might be more bossy when with their coworkers but less bossy with their friends. taking the average of their bossiness is possible, but how much information does that really provide? contexts are important. pathways principle - who cares if it takes someone two weeks to learn quadratics vs. 1 week so long as they learn it anyway. everyone’s different and shouldn’t be following same pathways. there’s upwards of 50 ways that a baby can learn to walk. maybe it’s starting to crawl, then walking, or maybe it’s walking right away, or maybe walking then crawling then walking again much later. overall, fantastic book. with lots of sense and interesting information from a learning-based perspective. 5/5 for the learnings.

Sergio

August 28, 2019

Un ottimo libro che non riguarda solamente lo sviluppo individuale o la gestione delle risorse umane in azienda, ma anche il sistema educativo e la formazione. L’autore analizza i successi storici di una serie di assiomi psicologici e manageriali basati sul concetto di “media” o di “distribuzione”, sostenendo che qualsiasi disciplina che alla basa abbia questi assiomi, tende a proporre soluzioni per persone “medie” che nella realtà non esistono. Corroborato da importanti studi sul tema (non sempre ben accolti dalla comunità scientifica), il libro analizza anche i danni provocati dai test di personalità, per giungere poi a proporre una soluzione veramente basata sull’individuo. Alcuni brevi casi reali mostrano come l’approccio abbia assolutamente senso. Nonostante sia ampiamente divulgativo, il testo è supportato da un’ottima ricerca bibliografica.

Ingrid

October 21, 2021

Af en toe te langdradig door bewijsdrang, maar interessante inzichten over het inzetten van gemiddelden. Tijd om zoveel mogelijk naar de grilligheid van het individu en de als/dan-relatie bij het gedrag van individuen in sociale contexten.

Adelita

August 06, 2022

If I could rate this book with 10 stars, I would do it!Mindblowing from beginning to end.

Marks54

July 05, 2016

I get wary of trade books focused around advances in social science, not matter how much they are touted in the trade press. That was my original thought with this book, but I am glad I went ahead and read it.What initially got my attention was when Rose newer thinking discrediting the importance of social science thinking based around means and standard deviations. For example when one consults studies of larger populations for guidance on hiring particular individuals. What is sought is a worker whose capabilities fit with the needs of particular employers in particular job situations not an employee who is seen as approaching the standard for some type. This is a huge issue in educational testing and reform efforts around the common core and related "innovations"....the problem is one that is chronic in applied social sciences and quite a few professionals know about it. To see the problem in a related setting, consider advice given to patients facing severe treatments. How does one.come to an estimate of five year survival of 75% when a particular patient survives or does not and most certainly will not replay the situation 10 or 100 times? Does one take the mean of a broader group? If so, how appropriate is that given the particularities of individual medical conditions.Rose then develops a broader story about how whole sectors of the economy have been shaped by "Taylorist" ideas ultimately based on overreliance on averages and work standards. While Taylorist critiques (and critiques of consultants in general) are thrown around too much in my opinion, Rose is generally on target with the story and it is well told. He also extends Taylorism to education and testing and by doing so provides good insight into the current battles over testing and reform. Rose is careful enough to know that one cannot just discredit mainline social science based institutions but must also suggest alternatives if the critique is to be useful. He does a good job in going over the enlightened hiring practices at a variety of cutting edge firms but in the US and Asia. The examples are well known but still interesting.Overall, this is a nice trade book that helps to put the meager statistics that most people know into a context that shows how statistical ideas can affect people, in good ways and in bad. That is a useful contribution to public discussions of work and education - and even health care. The book is very accessible and does not presume much statistical knowledge at all.

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.

![Manipulación [Manipulation]: Cómo analizar a la gente y mejorar tus habilidades sociales con estrategias probadas para defenderte de la manipulación, el control mental y la psicología oscura](https://speechify.com/audiobooks/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2023/07/pr_eaudio_9781662199882_640px.jpg)