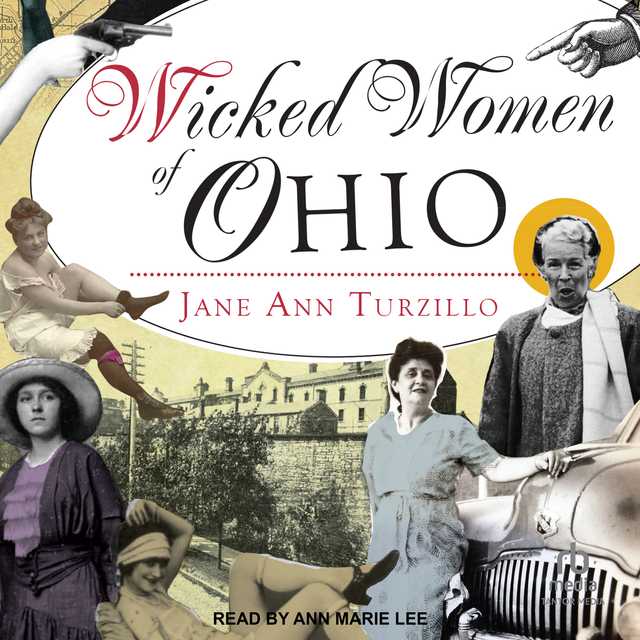

Village of Secrets Audiobook Summary

From the author of the New York Times bestseller A Train in Winter comes the absorbing story of a French village that helped save thousands hunted by the Gestapo during World War II–told in full for the first time.

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is a small village of scattered houses high in the mountains of the Ardeche, one of the most remote and inaccessible parts of Eastern France. During the Second World War, the inhabitants of this tiny mountain village and its parishes saved thousands wanted by the Gestapo: resisters, freemasons, communists, OSS and SOE agents, and Jews. Many of those they protected were orphaned children and babies whose parents had been deported to concentration camps.

With unprecedented access to newly opened archives in France, Britain, and Germany, and interviews with some of the villagers from the period who are still alive, Caroline Moorehead paints an inspiring portrait of courage and determination: of what was accomplished when a small group of people banded together to oppose their Nazi occupiers. A thrilling and atmospheric tale of silence and complicity, Village of Secrets reveals how every one of the inhabitants of Chambon remained silent in a country infamous for collaboration. Yet it is also a story about mythmaking, and the fallibility of memory.

A major contribution to WWII history, illustrated with black-and-white photos, Village of Secrets sets the record straight about the events in Chambon, and pays tribute to a group of heroic individuals, most of them women, for whom saving others became more important than their own lives.

Other Top Audiobooks

Village of Secrets Audiobook Narrator

Suzanne Toren is the narrator of Village of Secrets audiobook that was written by Caroline Moorehead

Caroline Moorehead is the New York Times bestselling author of the Resistance Quartet, which includes A Bold and Dangerous Family, Village of Secrets, and A Train in Winter, as well as Human Cargo, a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist. An acclaimed biographer, she has written for the New York Review of Books, The Guardian, and The Independent. She lives in London and Italy.

About the Author(s) of Village of Secrets

Caroline Moorehead is the author of Village of Secrets

More From the Same

- Author : Caroline Moorehead

- A Bold and Dangerous Family

- A House in the Mountains

- Mussolini’s Daughter

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

Village of Secrets Full Details

| Narrator | Suzanne Toren |

| Length | 13 hours 49 minutes |

| Author | Caroline Moorehead |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | October 28, 2014 |

| ISBN | 9780062205810 |

Additional info

The publisher of the Village of Secrets is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780062205810.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

David

September 19, 2014

Village of Secrets is a long and often complex book about how the people of the mountainous area of the south Massif Central in France helped to protect the Jews from the Nazis and helped many of them to escape to safety.It is so thoroughly researched that it is just about the book's only weakness that there are so many characters it's easy to forget some of them.In some ways Village of Secrets redresses the balance in revisionist French history which has tended to put its hands up in admitting responsibility for World Was Two collaboration yet perhaps not given true credit to those who resisted the German occupier. This book is also about religious tolerance. Catholics, Huguenots and other Protestant groups set aside their differences to save as many Jews as they could.The brutal truth is that tens of thousands of French people collaborated disgracefully with the Germans between 1940 and 1945 and many actively helped in the round ups of Jews. The attitude of the Vichy government towards the Jews is one the blackest moments in French history. Those punished at the end of the war deserved it.But, as Village of Secrets tells us, it is equally true that large numbers of the French people resisted, either actively or passively, and many were involved in trying to save the Jews, especially the children, from transportation to the Polish death camps. There were policemen, often with their own liberty at stake, who turned a blind eye to the hidden Jews. There were even some members of the Wehrmacht who did this.Inevitably, as in any Holocaust story, there are tragedies which Village of Secrets does not ignore. Ultimately, however, this great book is about brave people who put their own lives at risk to save those of others.David Lowther. Author of The Blue Pencil (thebluepencil.co.uk)davidlwtherblog.wordpress.com

Lewis

November 08, 2018

The story of Chambon is incredibly moving ... my wife and I had the experience of visiting the village and feeling the powerful sense of "goodness" which still resides there. This town, in a remote part of France, led by the Huguenot pastor Andre Trocme, was the place of refuge for perhaps 2500 Jewish children, hidden and then moved on to safety. (NOTE: see also my review of Phillip Hallie's "Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed: The Story of the Village of Le Chambon and How Goodness Happened There.")EXCERPTS ... On Saturday 26 August, 1942, some 50 to 60 police and gendarmes wound their way up the steep roads in police trucks and on motorcycles and stopped in front of the Mairie in le Chambon. Trocmé and the mayor were summoned and ordered to hand over the names of all Jews resident in the area.‘I am their pastor,’ Trocmé is reported as saying. ‘That is to say their shepherd.’ He said he had no idea whether there were any Jews among his parishioners, and had he known, he would not tell them. The policeman in charge informed him that he had just 24 hours in which to come up with the names, and that if he failed to obey, he personally would be arrested. As darkness fell, the children were collected by boy scouts and moved to more remote farmhouses, where they were hidden in attics or behind wood piles, only emerging after nightfall while the police remained on the plateau. When no list of Jews was forthcoming, the police, who had brought a list of their own with 72 names on it, began to search the village. They checked documents, opened cupboards, combed through cellars and attics, banged on walls to see if they contained false panels. They found no one. Next morning at dawn, they set out to explore the surrounding villages and the countryside ... Day after day, for three weeks, the villagers listened to the police firing up their cars and motorcycles in the early morning before leaving to scour the countryside for hidden Jews. They found no one. With the police finally gone, calm of a kind returned to the plateau. The Jewish children left the forests and the isolated farm buildings and came back to their homes and pensions; the pastors resumed their parish visits and Bible classes; the farmers once again took up the slow rhythm of their agricultural lives.

Nancy

October 15, 2014

here's how far behind I am -- I finished this book the end of last month and am just now getting to it here. aarrghh!Village of Secrets begins with the coming of the Nazis to France in 1940 and the establishment of the Vichy government under Pétain. It wasn't long until measures of repression against certain targeted groups ("foreign" Jews, Freemasons and Communists) began; the campaigns against them were accompanied by propaganda that targeted these groups as "dark forces of the 'anti-France'." However, as time went on, it became clearer that the Vichy government was expected to play a role in helping the Nazis implement their anti-Jewish policies -- not just the foreign-born, naturalized citizens, but eventually the French-born Jews, who'd mistakenly believed that their status offered them some modicum of safety. If you believe the myth that started circulating in 1953, a pacifist-oriented pastor named André Trocmé in the French parish of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon "helped save some 5,000 hunted communists, Freemasons, resisters and Jews from deportation to the extermination camps of occupied Poland." According to a magazine article that year, Trocmé had instilled his own belief in non-violent, peaceful resistance among his parishioners, and it was in this spirit that they were led to take in, hide, and sometimes get people whose names "appeared on Nazi death lists" safely over the Swiss border. Over two decades later, in 1988, Le Chambon was designated by Yad Vashem as the only village in the world to be "Righteous Among Nations," an appellation that in combination with a number of articles, documentaries, and memoirs about this remote village in the Massif Central, perpetuated the ongoing myth about Trocmé's role and that of Le Chambon as well. But there's a problem here: by focusing solely on this small, remote village and this peace-loving Protestant pastor, over the years that "myth" has ignored a lot of other people -- those from other places, of other beliefs, and even a number of humanitarian authorities who literally risked everything to help save people designated for the camps. In this book, the author takes on the realities behind the myths and examines the changing and still-controversial discourses evolving from this historical period. Either I add a too-long review, or you can click here for the long one at my online reading journal. Here's the short version: as its bottom line, this book most thoroughly examines how ordinary people responded to very extraordinary circumstances during this time period. It is a well written and meticulously-researched narrative that uses first-person accounts of people who lived to tell their tales due of the help they received from others, as well as accounts from some of those who helped them to survive. recommended. (my thanks to the publisher)

Lewis

May 19, 2018

I have read the sections of this remarkable account which pre-date the activities in Chambon ... a series of French Catholic and Protestant leaders resisted the Nazi demands to collect and deport Jews ... eventually, they realized that saving all the Jews was impossible and they chose to focus on the Jewish children.There are very few thrilling stories to emerge from the Nazi experience. This is one of them. Some excerpts ... ... the Maréchal (Petain) was aware that plans were going ahead to deport 10,000 foreign Jews … A gigantic net was already descending over Vichy’s internment camps. … The camps had been sealed. Throughout the countryside, convents, boarding schools, presbyteries and hostels were searched and the forests patrolled for Jews; those found were arrested... The trains were all bound for Drancy ... By the time Ella was taken from Drancy and put on a train for Auschwitz, there were three convois, transports, leaving every week ... The first transport to take children on their own, without parents, left Drancy on 17 August. Five hundred and thirty of the children on board were under 13. ... Between 17 and 31 August, seven trains left for Auschwitz. Among those on board were 3,500 children....For the children in Vénissieux, a new drama was unfolding. Three buses had arrived, driven by volunteers, to take the children away. Those over 18 – technically the age at which the Germans considered them to be adults – were concealed under the seats. Rachel’s only other memory of that time is of these hidden children. ... There was just time to scatter the children around Lyons, to convents, schools, hospitals and private houses. The older ones were put into scout uniforms and sent to join a pack leaving for a trip to the country. When the police arrived at the OSE office, the children had gone ... Chaillet declared that, in all conscience, L’Amitié Chrétienne would never hand over children entrusted into its care by their parents. Word got out. A leaflet with the words ‘Vous n’aurez pas les enfants’ was soon circulating around Lyons... ‘Let us save children by dispersing them,’ he said. For this, he added, Garel would need a cover, helpers, money, families, false documents and safe houses.

Richard

February 09, 2016

This is not the first time that an author has told the story of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon - an Alpine French community that was among those that hid Jewish children and adults during the Second World War, but it is the first account I have read. Caroline Moorehead is intent on correcting what she sees as the oversimplification and mythologisation of some earlier accounts. Other reviews on Goodreads certainly have taken her to task on this.But first and foremost it is an amazing and moving story. Families in the village and surrounding communities taking great personal risks to shelter thousands of Jews from the Nazis (and the French Vichy regime), and saving lives.We also hear about the individuals who took terrific risks to transfer Jewish families from camps and places of danger to the villages of the Alpine plain, or across the border into Switzerland.A huge amount of research has clearly been done, and although the cast of characters is large and confusing at times, the personal testimony is remarkable.Some though have accused Caroline Moorehead of downplaying the religious aspect of this story - diminishing the role of the Huguenot community and protestant pastors in sheltering Jewish families.But I do not think that's the case at all. Caroline Moorehead makes it quite clear how important a part the Protestant faith played in the decisions of individuals to help Jewish refugees.She just chooses not to make it a simple narrative of good versus evil. The truth is often more nuanced than myth, and many individuals played a part in this remarkable story, and many with different motivations. Jews were not just passive - many played an active part in saving lives. Catholics and those with no faith also were capable of heroic behaviour.Some of the most shocking parts of the book though expose the complicity of the Vichy regime in the attempts to exterminate Jews. There may have been no gas chambers - but Jewish families died in French-run camps because of starvation and illness, and Vichy officials allowed many more to be transferred to their death n the East. Anti-semitism was present in France - even if it was not as widespread and institutional as in Germany. But that just makes the heroism of those who chose to defy the Nazis and the Vichy government more inspiring. Some of those who helped save lives lost theirs in the cause.And, as in any real life story, there is ambiguity. The main French official may have actively helped to save Jews; he may just have turned a blind eye; but he also may have been culpable in some deaths. Equally the ambiguous attitude of the local German general may have made a contribution.Although many Jews did owe their lives to the village, this was far from a paradise. Many of the children lost their parents, and their identity. Not all their hosts were kindly. Some of those saved struggled to adjust to life after the war.So although there is hope and heroism here, there is also darkness and despair. These are ordinary people responding to extraordinary times - truth not fable - and I believe the book is more powerful because it is honest about that.And like many accounts of the Holocaust you ask yourself what your own response would have been to the same circumstances. We all hope we would "do the right thing" but how much would we be prepared to risk to protect others? Village of Secrets shows how difficult those choices always are, and how remarkable - and reprehensible - people can be.

Elizabeth

March 13, 2018

It can be difficult to comprehend all that happened in France during World War II—fighting against Germany, surrendering, collaborating, resisting, starving, running black markets, and of course bring up families and trying to stay alive. This book tells the stories of the people who lived in the tiny mountain village of le Chambon and the surrounding plateau, both the residents who hid Jewish men, women, and children whose lives were in peril and those they hid. Their stories are tragic, triumphant, and quotidian.History is finding meaning in details, otherwise it is a recitation of meaningless facts. Why did this tiny village become one of the few safe spaces for Jewish children, in particular? In part the answer lies in their Huguenot past. Persecuted since the 17th Century, the people of Le Chambon valued life and sympathized with the situation of the hunted. They were a tight-knit and tight-mouthed group, able to keep secrets. Local ministers were central to the system both as spiritual leaders and as the hub of information networks that were necessary. In addition, the French authorities were often, bit not always, willing to look the other way. The power of this book is in the stories of the families that stayed there and their hosts. Le Chambon was a summer holiday destination, so rooms were plentiful. Aid groups brought Jewish children to the village where they were quickly moved out to family hostels or isolated farms. One man made a full-time job of forging convincing identity papers and ration books for every displaced person. Local cafe owners passed on useful intelligence about what the Germans were up to. The prefect of the Haute-Loire Departement appeared at times to ignore clear evidence of subterfuge but at other times he seemed to collaborate with the Nazis (he was cleared of collaboration by a tribunal after the war on the grounds that he did what he could). It’s the stories of the children that are the most heartbreaking. The came from every social class and background. Many were French by birth but their Jewish parentage marked them for deportation and extermination. Their parents sent them alone with strangers to a new life. When they later met their parents, many did not know them and wanted to stay on the plateau with their foster families. Many were emotionally hollowed out by the experience. As the Nazi net tightened around the plateau, the resistance grew and spawned an active group of men and women who acted as couriers, saboteurs, assassinators, and local militia. Not wanting to attract attention to the place where so many were hidden, it fell to local leaders to calm down and moderate the group’s actions, no easy task.In an Afterword, the author reveals the subsequent lives of many of the major players, who became a kibbutz member, who a social worker, who a farmer, and who a success in business. Their afterlives reveal the ordinariness of the people caught up in this extraordinary drama.Le Chambon was not an isolated case. An old friend, since deceased, told me the story of his teen years hidden in the isolated village of Gap in the Alps, where his parents sent him to avoid being drafted by the Germans for work in munitions factories. He described his life in the “auberge de la jeunesse” as not unhappy. He went on to expand his family’s ancient mustard business in Dijon into an international food conglomerate and enjoyed life thoroughly into old age.One quirk of this book: the translator has consistently translated the common French word, sportif, as sporty instead of athletic, which made for some odd descriptions.

Janet

April 12, 2020

Moorehead doesn't gloss over facts. A lot of French people were antisemites, including intellectuals like Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre to my disappointment.Even the indifferent were outraged when the Vichy government started deporting children. This is a fascinating portrait of a time and place where one had to choose sides when the costs were tremendous and it wasn't always easy to know whom to trust.

Brett

July 04, 2022

As I continue to embrace audiobooks, I was excited to come across Caroline Moorehead’s, 2014 book, Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France while at the library. As a baseline, WWII is a broadly interesting subject matter, obviously, but I’ve specifically been interested in learning the large segments of it I still don’t know much of anything about, like Stalingrad, England’s role, and France’s resistance to the Nazi occupation. The audiobook is read by Suzanne Toren.I do have to admit, I found the audiobook hard to follow as an English-speaker, and perhaps also due to my general ignorance of the subject matter. Maybe it would have been “easier” to follow if I was reading it versus listening to it? But a fair amount didn’t translate, literally, for me, and it was particularly hard to keep up with different character names and such. That’s just a language barrier thing, but also, I say “literally” because sometimes, certain passages weren’t translated into English, so I didn’t get the added context.That difficulty aside, it’s impossible not to be enthralled by the real life story of France folding to the Nazis for myriad reasons, the Vichy government of France, which collaborated with the Nazis, and the resistance types of all stripes, who pushed back nonviolently and violently, and also, saved scores of Jews from the Holocaust (as well as other resisters, Freemasons, and communists), primarily children.Much of the latter resistance took place in a particular French village, Le Chambon-sur-Lignon on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon.Moorehead argues off the top that the latter is perhaps overwrought in modern French myth-making in the sense that, 5,000 Jews weren’t saved by inhabitants of the village, but more like 800 were hid there, and perhaps 3,000 crossed through the village on the way to Switzerland, but to what extent they were aided is unclear. And I think, if I’m understanding Moorehead right, her theory would argue, the reason there is myth-making about Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is to compensate for the shame and guilt France collectively feels toward enabling the extermination of the Jews through collaboration with its police forces, Vichy government, and a general anti-Semitism even before the Nazis came to Paris.Something I couldn’t help but think about, too: Religions, sometimes rightly, get lumped in as appealing to our most base impulses with deleterious consequences, but they also appeal to our most humane impulses, too. After all, many of those who saved the Jews in France (and elsewhere in Europe) were deeply religious. In this case, Moorehead is talking about Protestants primarily, the Huguenots and Darbyists. It was their faith that called them to be the sort of people who stood athwart the wave of anti-Semitism washing over the globe, and backed by the guns of the Nazis and the Gestapo, and said, “No, we will not partake.” And in fact, “We will actively resist and provide safe harbor to those in need.”That level of courage and bravery, which they wouldn’t think of it as anything other than an obvious and even ordinary thing to do, sends goosebumps up and down my flesh. It is the sort of person I aspire to be, if ever a moment like it arises.I was particularly enamored by the story of Pastor André Trocmé and his wife, Magda, of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, who actively spoke out against Nazi Germany and advocated for helping to hide Jewish refugees. He was also a strident pacifist. It is hard to overstate how immensely courageous it is to stand at the pulpit when Nazis are swarming the land, and when fellow French citizens are collaborating with the Nazis, and say to your congregation, “We will resist when our enemies demand from us things that our teachings forbid or that contradict the commands of the gospel.”Another character I was enamored by was Virginia Hall, an American who worked in France during WWIII, specifically with the resistance forces. It is cliché to refer to a woman as bad-ass, but if anyone deserves that honorific, it is Virginia Hall. She was the first female agent in France who supplied pretty much anything the resistance needed, and then was still able to evade capture and escape France. She received the Distinguished Service Cross after the war, the only one awarded to a civilian woman. She didn’t even care to get a medal from President Truman because she said she was “still operational.” She also seemed famously, as Moorehead explains, to demur on talking about her activities during WWII or thereafter, which is probably why there hasn’t been that many big movies about her.So, Moorehead shows these twin forces going on in France at the same time. First was the rising anti-Semitism in France on the eve of another global war. As she points out, France had more immigrants by percentage around 1938 than all of Europe (I believe that’s right), but when the economic downturn that was affecting the rest of the globe finally washed ashore France, they blamed the Jews, felt there was “Jewish saturation,” and the government and citizens wanted to expel them.One woman powerfully said that bombs didn’t scare her because they are indiscriminate, but anti-Semitism did because it targeted the Jews.When the Nazis occupied France, I was surprised at how French politicos, pundit types of the day, and citizens blamed the French Republic becoming a “republic of women and homosexuals,” and essentially, drowning in too much liberty. That in fact, it was such decadence which caused the Nazi occupation, and France, in a way, deserved what she sowed. (Digression, but there is a throughline of a kind between that thinking then, and the thinking now among the American right that what befalls America is deserved for our own decadence in our own time.)Secondly, the other current, is of course the minority of religious leaders, like Trocmé, who were primed to resist and to hide. It seemed these religious leaders were in the minority. While I gave religion credit earlier, here is where it gets its criticism: France was predominately a Catholic country, and there were those agitating to “re-Christianize” France and end the separation of church and state (which from what I can tell stretches back to 1905) as a response to the Nazis.I also find the Vichy government bizarre: They were so worried about bad press beyond French borders, where other countries would learn about what they were doing to enable the discrimination and extermination of the Jews, and it’s like, huh? That tells me they knew they were doing something wrong, right? If they believed in what they were doing and thought it righteous, why be ashamed? The primary issue is the actual discrimination and aiding and abetting extermination, but that secondary follow-through of trying to obfuscate that you are doing it fascinates me, too. So much energies get expelled on trying to deny that which you are clearly doing.Unfortunately, a familiar theme arises in, Village of Secrets, if you’ve read any prior Holocaust stories: The belief that persecution will only be applied to them, but not us. French Jews figured such persecutions would only be applied to foreign Jews, but not French Jews, and thus, they had nothing to fear. But of course, such persecution didn’t stop with foreign Jews.Another Jewish woman was quoted as saying about living in France during WWII, “We live somewhere outside life in a bath of death.”In the time it has taken me to listen to the audiobook, I’ve noticed, incidentally, that the Auschwitz Memorial Museum on Twitter, which regularly posts pictures and names of those who perished in the Holocaust, were Tweeting out the French ones. Like a French girl, Anni Molho, who was born in Southwestern France, and at age three, was gassed at Auschwitz. (I recommend giving them a follow, by the way. They are trying to reach 1.5 million followers.)Or another French Jewish girl, Jeanine Nicole Heimer, who also perished at Auschwitz. She would have only been around 14-years-old.That is what we are talking about: Collaboration meant death for three-year-old girls like Molho, and 14-year-old girls like Heimer, for no other reason than hatred of their Jewishness. Collaboration meant terrible, ugly treatment and separation from their parents. And collaboration meant that parents pleaded and begged for governments, like the United States, but others, too, to take their children, and to save their children.Back to Trocmé, his inspiration, in part, was Deuteronomy 19:10, which states, “Do this so that innocent blood will not be shed in your land, which the Lord your God is giving you as your inheritance, and so that you will not be guilty of bloodshed.”In Trocmé’s interpretation, he took innocent blood to mean the refugee. And I believe it is he who Moorehead quotes as saying, “I believe in the final triumph of good over evil.” Without violence, mind you, as again, he was a pacifist.Another rebellion quote about the Vichy government was, “I will disobey if justice and truth demand it.”You can see why, as Moorehead argues, that the French have so ardently held to the myth-making of a kind about Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, because it’s much better than confronting the ugliness of that time period, what the French refer to as “les ann es noires,” or “the dark years.”But also, in some ways, the retaliation and vengeance was swift, and a stark contrast to Trocmé’s pacifism: Moorehead mentions that the resistance executed 9,000 Nazis and/or collaborators.I also found the Afterword that Moorehead does when the war ends fascinating, to see where those who helped or survived ended up (many in America, Israel and elsewhere), and of course, how the French reckoned, or didn’t, with its collaboration with the Nazis.To the former, one person was quoted as saying about why he couldn’t stay in Europe, “Europe had become one vast Jewish cemetery.”The death toll of six million Jews is nearly unimaginable (until you see the pictures and names, which is why I recommended giving the Auschwitz Memorial a follow on Twitter), but also, there is the ripple effect of that trauma, as explained by that quote.History, by its nature, feels like the distant past, far removed from the present, but we can’t forget that there are still Holocaust survivors alive right now! Heck, there was just a Nazi sentenced for WWII crimes at the age of 101!History is the present, and it is the clarion call to ensure it doesn’t become our future. For that reason, I recommend, Village of Secrets. It is a challenging listen (and so, I imagine, a challenging read), but well-worth it.

Dennis

April 12, 2021

Although in some ways this is a sad book to read, it is also uplifting to learn that despite the onerous penalties, French people with humanity still worked to help the Jews, and particularly Jewish children to escape from being shipped to the Nazi extermination camps. However, this is balanced by the overwhelming numbers of French people who reported Jews to the Gestapo, despite knowing that they would be transported to the camps and gassed. Even worse, many provided this information in return for a reward. Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is singled out for special reference as this remote French location sheltered many Jewish families, and particularly children, from the Gestapo and later became a centre for the French resistance. The work of several Protestant clergy is singled out for their dedicated work. As I have said earlier, in some ways this could be regarded as a depressing book about man's inhumanity to man, but it is also a book that recognises the people, who despite the penalties did what they knew was right.

Michael

April 29, 2015

The author has done an incredible amount of research for this and brings all of the research together so that is woven like a novel where all that she relates flows, and there are so many characters and incidents. The basis of the book is that this village on a plateau near Switzerland was used as a hiding place and conduit, especially for Jewish people, to try and assist them with escaping from the clutches of the Nazis. The focus is on how the organisation for escapees functioned, who the main players were and why they participated in assisting these people move to safer areas, despite the threat of death for giving such assistance. As people of the Jewish faith fled from Poland and other Eastern countries, the Nazi organisation kept tightening the noose and there were regular bulletins imposing more and more restrictions on the Jews so that even in Vichy France (large southern area of France controlled by a puppet French Government on behalf of the Nazis) where many had fled, the relentless pursuit and restrictions continued.Not surprisingly, many French citizens were willing to collaborate with their new masters in the hope that one day they would receive their rewards once the war was over. This then raises an interesting position for the author, for despite her thorough research, she has found many conflicting statements and pieces of evidence from those who are still alive. They have their current lives and lifestyles to maintain, and some also wish to be seen in whatever positive way possible, and consequently change their story to fit the desired outcome. The dynamics of a written history come to the fore. It has certainly helped me understand why so many of the French are so reticent in talking about their experiences during WW2. A very interesting read about how humans do try and help others in times of extreme adversity.

Stephen

April 06, 2016

Of all the European nations torn apart by the 2nd world war and its aftermath, France is the one that has had the longest and greatest difficulty in dealing with it. It went through the immediate aftermath of dealing with a long list of collaborators and 'alleged' collaborators, then focusing for many years on the role of the 'resistance'. It was only in the 1970s that the country was forced to come to terms more fully with the extent to which the Vichy regime had not only co-operated with the Nazis but gone beyond what they were asked to do in relation to the jews and other 'undesirables'. Compared to other occupied countries, it did the least to protect its jewish citizens.More recently, there has been a return to recognising the role that many ordinary French citizens played in protecting both jews and ooponents of the Nazis, coinciding with the naming of a wide range of individuals as 'Les Justes'. Caroline Moorehead's book concentrates on these citizens and tells the individual stories in grest detail and, at times, with almost thriller-like suspense. However, what is most interesting about the book is her analysis of why this particular area of the Central Massif and these particular people behaved in the way that they did. In passing, she also tells the other side of the story - the complicity and more than subservience of the Vichy regime in rounding up jews and others and sending them to the death camps.Despite the fact that all this happened 70 years ago and there have been endless books written about it, ti is still a subject that fascinates and appalls.

Girl with her Head in a Book

August 21, 2015

For my full review: http://girlwithherheadinabook.co.uk/2...The beautiful myth of French resistance loomed large in our cultural imagination for decades post-war, summoned up in comedy such as in the sitcom 'Allo 'Allo, in war films such as The Great Escape but most of all, it was eagerly embraced by the French people themselves who were eager to reimagine a nobler history. Caroline Moorehead examines all sides in Village of Secrets in this in-depth and often harrowing account of the persecution of the Jews in wartime France. The village of the book's title is le Chambon-sur-Lignon, an apparently ordinary and sleepy French town set high in the mountains but one where approximately three thousand Jews were hidden successfully. Jacques Chirac praised the area as the nation's 'conscience' and in 1990, the town was honoured as Righteous Among Nations. However, Moorehead points on from very early on that there are several variations to the story and her book analyses not only the assorted divergences but also how ownership of memory itself can become a battleground. Full of first-hand accounts and dealing some painful truths, Village of Secrets invites the reader to wonder - what would they have done in that situation?From very early on, Moorehead makes it clear that the Vichy government were independently keen to serve up their nation's Jewish population to the Germans. As the book continues, the contrast is made between their conduct and that of Denmark, who managed to save 93% of their Jews by getting them into Switzerland. Fascist Italy also dug in their heels and refused. It was Pétain's government who time and again handed over more people than were requested, desperately searched for more Jews to bundle onto trains, stretched the rules and betrayed their own people. Even the Nazi officers themselves remarked that there was 'little difficulty' in persuading the Vichy officials to comply. Just how far their attitudes summed up nation-wide opinions is unclear but one cannot help but be reminded of the bitterness behind eyewitness Irene Némirovsky's novel Suite Française which vividly summons up a country turning against itself. Moorehead quotes one veteran as remarking that the French did not much like each other as the war broke out, and they did not much like each other afterwards.The story of the resistance within le Chambon is perhaps most appealing because it seems so mundane - good, hardy country folk who chose to do the right thing. It has a personal interest for me because in the summer of 2008, I worked in an English language immersion summer camp in that town. It is a two hour drive up the mountain to reach the summit, all of this with hairpin bends every couple of hundred metres. The forests are thick, the winters are long - Le Chambon is remote in the extreme. When one truculent camper demanded that her mother come and collect her, we joked that she would need a helicopter. It is a quiet town and the locals tend towards the taciturn yet I was struck by how strong its sense of community was. Moorehead's book conjures up vividly the streets I ran down, the river we used to go and sunbathe beside on our day off - it is a stunningly beautiful place but it is one which bears the weight of history. We took the children on the steam train for a day out; the train is small, there are two passenger carriages and then one at the back which looks more like a horse box and is there to make up weight. One local explained that the rear carriage had originally been used for transporting Jews.caroline mooreheadMoorehead narrates the steady downfall of the Jews chronologically, starting with the internment camps for the 'undesirables' of the Vichy state - the communists, the gypsies, the foreign Jews. Conditions were horrendous; in Gurs alone, one thousand people died just in 1941. Outside attempts to provide aid to the detainees were blocked at every turn and even as the charities seeking to provide food and healthcare did their best to grit their teeth and work with Vichy, it became clear that they were only setting the trap - the camps were not the worst case scenario. Deportation fever swept across the camps. Again, the Vichy enthusiasm to please the Germans and dispose of as many Jews as possible is stomach-turning. Doctors and church officials raced around trying to declare as many as possible as unfit to travel. Exemptions were sought for children. Vichy refused.There are some stories of success - children smuggled out in cars, under coats, in shopping baskets. Having discovered the night beforehand that officials were coming to deport the Jews, Abbé Glasberg and others went through the camps with hastily typed permission slips asking for parents to suspend guardianship of their children so that they could be taken away and hidden. Eighty-nine children were saved that night, a number of whom would end up in le Chambon.Moorehead details the history of the Haute-Loire area, of their ties to the religious wars with the strong Protestant community descended from the Huguenots. They understood what it meant to be persecuted, they had survived the revocation of the Edict of Nantes - these were people who well understood the concept of discretion. They had read the Old Testament, the importance of sustaining the oppressed and sharing what one had. The general myth of le Chambon makes the dynamic local preacher André Trocmé the hero who called upon his parishioners to shelter those in need, yet Moorehead emphasises that the truth is more complex. Either way, there was a long history of children and young people being sent for holidays up into the mountain for the good air.Resistance workers would bring groups of children and endeavour to place them - under the code, the Jews were referred to as stationery and often 'old Testaments', with one of the curates writing to his parents cryptically that he felt very blessed that the locals were so welcoming to this kind of literature. The children were hidden in plain sight, the strong culture of silence preventing discussion of what was truly going on. One local child was surprised to discover later in life that those youngsters who had lived in her family's pension were in fact Jewish. As another local pointed out, the people of le Chambon were 'pas bavards' - not talkative. Yet despite the 'don't ask, don't tell' attitude, it is clear that they were aware of what they were doing. One agent had difficulty placing a pair of teenage boys, since boys were generally held to be more difficult but when in desperation she told the farmer that the pair were not mere refugees, but in fact Jewish, the farmer responded impatiently that in that case, of course they would take them and that she should have just said that in the first place. When the town police were first ordered by Vichy to flush out any hidden Jews, they went into local cafes and loudly announced their itinerary, then waited a while before setting off.Still, despite inspiring tales, this is not a book with happy endings. Some children found their hosts cruel, others simply mourned their childhoods cut short. Simon Liwerant and his infant brother Jacques made their way up to le Chambon but the trauma of what had befallen them prompted a bout of bedwetting in Jacques which caused his host mother to threaten to put the child out of the house. After lengthy remonstrations and having reached desperation, the young boy Simon struck the toddler Jacques. The bedwetting stopped but the bond of brotherhood was struck asunder. Even after the war was over, Jacques never forgave his brother. Even those children who were reunited with their parents had to deal with people they barely recognised, traumatised and prematurely old. In later life, one remarked that in this situation, they did not even have the luxury of being an orphan.Trocmé attempted to preach a message of nonviolence and it is this which the town became known for. A group of German soldiers were sent to convalesce in the town hotel, yards from where Jewish children were being hidden and by and large, matters passed without incident. 1943 however was a tough year, for those trying to act as saviour as well as those in hiding. There are stories of true heroism however in those were caught; Marianne Cohn acted as passeur in guiding Jews across the border to Switzerland but was eventually caught and beaten to death. There had been a possibility to save her but she refused to take it lest reprisals fall on the children. Dr Le Forestier was one of the more exuberant characters of the book, seeking to amuse the children who had been through so much and blasting his car horn whenever the Germans tried to play their music. He was shot. Nicole Weil had worked hard to get children out of Nazi-controlled Nice but was caught and sent to Auschwitz where she took charge of three small orphans. Refusing to give them up even though she was exempted as a worker, she chose to follow them into the gas chamber. The litany of the lost is crushing and seemingly without end.More than anything however, Village of Secrets makes it clear that the truth is rarely simple. For every person who is hailed in one place as a hero, there is another story that undermines them. The wonderful Madeleine Dreyfus saved countless children and managed to survive arrest and being sent to a concentration camp. When she returned home, she was back at work again within weeks. Yet her daughter remembers bitterly that her mother seemed to have time for all of the children in the world except her own. The Nizard family nursed a bitterness towards the undoubtedly well-intentioned young curate who failed to let the network know of their father and brother's arrest in a timely enough fashion for them to be rescued. The 'sainted' Trocmé is held as naive and self-deceiving by members of the community who point out the hard work of the Catholics, the Darbyists and others who worked hard to keep the Jews safe - not to mention the active local maquis network who certainly did not practice non-violence but who did save lives. Additionally, while some versions of le Chambon story puts the local police chief Schmähling as a hero who kept the Nazis off the trail, others point out that he allowed the murder of Dr Le Forestier and was happy to allow certain arrests take place. Even Inspector Praly, sent up to spy on 'the movements of Jewish refugees' and eventually assassinated, was described by some as having tried to stop the Jews being caught.The story of le Chambon is one that rumbles on in discord - Moorehead notes the particular French obsession with national identity and memory. It took thirty years to agree on a museum within le Chambon and even the publication of this book itself prompted a fresh outbreak of disagreement. This seems unbearably sad because in so many ways, Village of Secrets reminds one again of the words of Schindler's List, that he who saves a life saves the world. More should have been done - the camps in Auschwitz should have been bombed, the Vichy government should not have betrayed its citizens (and that sentence does not even begin to describe the depth of their crimes), there were times even in le Chambon when warnings were missed and lives not saved. But as Moorehead describes the eventual careers of the survivors, that Max and Hanne Liebmann grew up and married each other, that Pierre Bloch thanked the people of le Chambon for his 'happy childhood as a little Jew during the Holocaust', one would wish that they could be celebrated for themselves - one would wish for healing.Village of Secrets is crammed full of stories from survivors, tales of courage, betrayal, failure, success, hope, despair. It is a helter-skelter ride through the most extreme of human experiences. At times Moorehead's book is almost disorientating in its scope and reach. Her style is restrained, yet her judgment on the behaviour of Vichy is stern. With such a vast cast of characters, it was hard to keep track of everyone but yet all those who crossed the page emerged as flesh-and-blood humans. So many incidents are described in just a few lines and yet evoke such powerful emotions. For all the arguments of who did what and thought what and said what to whom and to what import, Moorehead is telling a story that needs to be remembered because the story of that beautiful village up in the Haute-Loire goes so much to the heart of what it means to be human.

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.