The Spider Network Audiobook Summary

The Wall Street Journal‘s award-winning business reporter unveils the bizarre and sinister story of how a math genius named Tom Hayes, a handful of outrageous confederates, and a deeply corrupt banking system ignited one of the greatest financial scandals in history.

In 2006, an oddball group of bankers, traders and brokers from some of the world’s largest financial institutions made a startling realization: Libor–the London interbank offered rate, which determines the interest rates on trillions in loans worldwide–was set daily by a small group of easily manipulated functionaries, and that they could reap huge profits by nudging it to suit their trading portfolios. Tom Hayes, a brilliant but troubled mathematician, became the lynchpin of a wild alliance that among others included a French trader nicknamed “Gollum”; the broker “Abbo,” who liked to publicly strip naked when drinking; a Kazakh chicken farmer turned something short of financial whiz kid; a broker known as “Village” (short for “Village Idiot”) and fascinated with human-animal sex; an executive called “Clumpy” because of his patchwork hair loss; and a broker uncreatively nicknamed “Big Nose.” Eventually known as the “Spider Network,” Hayes’s circle generated untold riches –until it all unraveled in spectacularly vicious, backstabbing fashion.

The Spider Network is not only a rollicking account of the scam, but a provocative examination of a financial system that was crooked throughout, designed to promote envelope-pushing behavior while shielding higher-ups from the consequences of their subordinates’ rapacious actions.

Other Top Audiobooks

The Spider Network Audiobook Narrator

Mike Chamberlain is the narrator of The Spider Network audiobook that was written by David Enrich

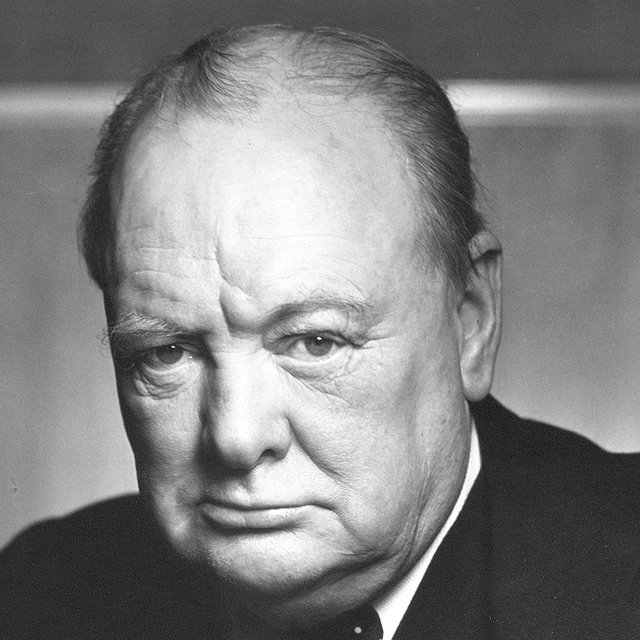

David Enrich is the Business Investigations Editor at the New York Times and the #1 bestselling author of Dark Towers. He previously was an editor and reporter at the Wall Street Journal. He has won numerous journalism awards, including the 2016 Gerald Loeb Award for feature writing. His first book, The Spider Network: How a Math Genius and Gang of Scheming Bankers Pulled Off One of the Greatest Scams in History, was short-listed for the Financial Times Business Book of the Year award. Enrich grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, and graduated from Claremont McKenna Collee in California. He currently lives in New York with his wife and two sons.

About the Author(s) of The Spider Network

David Enrich is the author of The Spider Network

More From the Same

- Author : David Enrich

- Servants of the Damned

- Dark Towers

- Publisher : HarperAudio

- Abraham

- American Gods [TV Tie-In]

- Dead Ringer

- House of Sand and Fog

- Prey

The Spider Network Full Details

| Narrator | Mike Chamberlain |

| Length | 15 hours 31 minutes |

| Author | David Enrich |

| Category | |

| Publisher | HarperAudio |

| Release date | March 21, 2017 |

| ISBN | 9780062659972 |

Subjects

The publisher of the The Spider Network is HarperAudio. includes the following subjects: The BISAC Subject Code is Banks & Banking, Business & Economics

Additional info

The publisher of the The Spider Network is HarperAudio. The imprint is HarperAudio. It is supplied by HarperAudio. The ISBN-13 is 9780062659972.

Global Availability

This book is only available in the United States.

Goodreads Reviews

☘Misericordia☘

March 19, 2019

A very cool research on a very space cadet issue that our modern world, no matter how sophisticated we think it be, was prone to at up until a very recent point. (And probably still is, I don't see this process becoming separate from judgement!)Q: Spread out across time zones and continents, a group of bankers, brokers, and traders had tried to skew interest rates that served not only as the foundation of trillions of dollars of loans, but also as an essential vertebra of the financial system itself. It all boiled down to something called Libor: an acronym for the London interbank offered rate, it’s often known as the world’s most important number. Financial instruments all over the globe—a volume so awesome, well into the tens of trillions of dollars, that it is hard to accurately quantify—hinge on tiny movements in Libor. In the United States, the interest rates on most variable-rate mortgages are based on Libor. So are many auto loans, student loans, credit card loans, and on and on—almost anything that doesn’t have a fixed interest rate. The amounts that big companies pay on multibillion-dollar loans are often determined by Libor. Trillions of dollars of exotic-sounding instruments called derivatives are linked to the ubiquitous rate, and they have the ability to touch virtually everyone: Pension funds, university endowments, cities and towns, small businesses and giant companies all use them to speculate on or protect themselves against swings in interest rates. If you bought this book with a credit card, you quite possibly brought Libor into it. So, too, if you drove to the bookstore in a car not yet paid off—or if you’re carrying a mortgage or student loans, or if your town borrowed money to pave its roads, or if you work for a company that issues debt. So if something was wrong with Libor, the pool of potential victims would be vast. As it turned out, something wasn’t wrong with Libor, everything was. (c)Q: … this was a misadventure like none other. (с)Q: Of course, traders being traders, Davies teased Hayes about the fact that his mother still cut his hair and that he was still sleeping under a duvet cover decorated with superheroes. He suggested that his mentee read The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a novel whose autistic main character reminded Davies of Hayes. (Behind his back, Davies nicknamed him “Kid Asperger.” Other colleagues christened him “Rain Man.”) (c)Q:Derivatives really exploded in popularity in the 1970s, in large part due to unprecedented volatility that hit financial markets. Oil prices ricocheted up and down. Governments delinked their currencies from the gold standard, causing exchange rates to swing wildly. Rapid inflation spurred central banks to jack up interest rates. Companies and individuals needed ways to protect their fortunes from these new risks—and banks and brokerages were there to help, peddling a growing array of derivatives. A company that offered hot-air-balloon rides might purchase derivatives whose value rose the more rainy days there were in a season, thereby shielding the company from the adverse effects of bad weather. The banks or other companies that sold those instruments would charge a fee and then would try to balance out their positions by offering the opposite positions—say, a derivative whose value climbed based on the number of sunny days—to other customers, such as umbrella manufacturers. Boiled down to their essence, derivatives were designed to help people or institutions protect themselves from future circumstances. And no matter the sunshine or the clouds, one party in the transaction always came out ahead—that was the bank that, for a fee, engineered the derivative. Derivatives were uniquely suited for speculation, because traders could dabble without actually having to own a product. Someone who bought or sold pork belly futures, for example, was unlikely to actually own, now or ever, any actual pig parts. But future swings in the price of pork bellies might be a good gauge of expectations about the weather or a harvest or a disease’s severity or just basic macroeconomic trends. And so investors might buy or sell pork belly futures to get a piece of that action. (c)Q:And in 1998, the chaotic collapse of the giant, derivatives-investing hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, run by mathematicians and Nobel Prize–winning economists, further underscored the instruments’ risks (c)Q:In 1981, IBM turned to Salomon Brothers for help. The Wall Street firm approached the World Bank—one of the leading issuers of debt anywhere, and an entity with a tolerance for bonds denominated in a variety of currencies—and convinced it to sell a slug of bonds that were identical to the IBM debt except for one crucial difference: They were in dollars. Then IBM and the World Bank simply swapped responsibility for making interest payments and eventually repaying the principal on their respective bonds. It was the birth of a new financial derivative: the swap. (c)Q:From the start, though, Libor was prone to problems. Chief among those was the potential for banks to manipulate it for their own benefit. Doing that was alarmingly easy. In the 1990s, junior bank employees would simply pick up the phone and call in their submissions to financial data company Thomson Reuters every morning around eleven o’clock. A low-level Reuters employee punched all the banks’ data into a computer and calculated the averages. Nobody of any seniority monitored the process. Virtually all it took for a bank to skew Libor was for it to skew its own submission. As long as the bank’s figures weren’t the very highest or the very lowest of all that day’s submissions, a change in its data would ripple through the average. In 1991, a young Morgan Stanley trader in London named Douglas Keenan was placing bets on interest-rate futures. Their value was calculated based on where Libor moved. After the market moved against him one day, Keenan came to suspect that someone—he wasn’t sure who—was somehow manipulating the instruments to suit his or her own trading positions. He shared his suspicions with his colleagues. They laughed at his naïveté. It was common knowledge that banks tweaked Libor to benefit their own trading positions. It seemed that everyone other than Keenan already knew it was happening. Banks had multiple incentives to push or pull Libor. One was that, because each bank’s submission was made public, investors scoured the data for indicators about the bank’s financial health. A bank that reported a spike in its borrowing costs might be in trouble—after all, why else would rival institutions suddenly be charging it more to borrow row money? That gave banks a reason to keep their submissions low, especially during periods of market unease. Another enticement for banks to tinker with Libor was to increase the value of the vast portfolios of derivatives that the banks’ traders were sitting on at any given time. Those positions could incentivize a bank to move Libor higher or lower—or both, in the frequent event that different traders at the same bank had amassed different positions. It all depended on what their traders had recently bought or sold. (c)Q:When the CFTC invited the public to comment on the Merc’s proposal, Marcy Engel jumped at the opportunity. Engel was a lawyer for Salomon Brothers, then firmly established as one of Wall Street’s most aggressive bond-trading houses (it soon would become part of Citigroup). She worried that linking Libor to the Eurodollar futures would provide banks, which had huge businesses trading those contracts, “an opportunity for manipulation . . . to benefit its own positions.” Richard Robb, at the time a thirty-six-year-old trader at a small Japanese financial company, DKB Financial Products Inc., also wrote to the commission to caution that Libor was vulnerable to manipulation and therefore shouldn’t be embedded in the contracts. “If two banks worked together, they could raise the average” substantially, he warned. During Bill Clinton’s presidency, the CFTC had earned a reputation as a hands-off, probusiness regulator. In December 1996, staffers wrote a memo to the agency’s leaders saying that Libor “does not appear to be readily susceptible to manipulation.” The commission approved the Merc’s application. The next month, Libor officially became an integral component of the fast-growing derivatives market. (c)Q:One way for the BBA to wring more revenue out of Libor was to create new versions of the benchmark. The most prominent versions of Libor were the British pound and the U.S. dollar varieties, but by 2005 Libor came in ten flavors: The pound and dollar were joined by the Australian dollar, the Canadian dollar, the Swiss franc, the Danish krone, the euro, the Japanese yen, the New Zealand dollar, and the Swedish krona. And within each of those, there were fifteen subcategories, broken down by time periods. For example, a three-month U.S. dollar Libor was supposed to measure how much it would cost a bank to borrow dollars in London for a three-month period. Other time periods included one month, six months, one year, and so on. (c)Q:Smith had basically no clue what he was doing. He didn’t know how to go about figuring out the bank’s borrowing costs, which were supposed to be the entire basis of the bank’s Libor data. He didn’t even know whom to talk to internally. … So Smith, lacking much other relevant information, would make up his submission based in part on what the brokers were predicting. …Brokers weren’t Smith’s only sources. One of the investment bank’s priorities at the time was to improve collaboration between different parts of the company. The idea was to transform UBS into a more efficient, collaborative beast, with everyone aware of what his colleagues were up to and pulling in the same direction. The directive was communicated down the chain of command by a senior manager named Holger Seger, a veteran trader who’d worked at UBS and before that Swiss Bank Corp. since 1990. It might have sounded like a vacuous corporate platitude, but UBS employees, at least some of them, took it seriously. Smith was supposed to coordinate with UBS’s traders who specialized in buying and selling interest-rate swaps, instruments whose values rose and fell based on movements in Libor. Sometimes the swaps traders would lob a request in his direction about where they wanted him to submit the bank’s Libor data that day. Even as a rookie on the desk, he understood what was going on. The traders had big positions whose values hinged in large part on Libor—precisely what Marcy Engel and Richard Ross had warned the CFTC would happen. A lot of money was on the line. So Smith generally followed their requests when it came to what he entered into his spreadsheet. He didn’t see any reason not to. (c)Q:Around 7 a.m., he sent out an e-mail called a “run-through” to a slew of bank traders. The dispatch contained a simple spreadsheet—basically just a box of numbers—pasted into the body of the message. It listed where every tenor—the technical term for time period*—of yen Libor had stood the past day or two and where Goodman expected it to end up that day. He called that last figure “Suggested Libors.” Each morning, he prefaced the data with the same simple note: “GOOD MORNING YEN RUN THRU.” The run-throughs had been an ICAP fixture since the late 1990s. Before long, ICAP’s marketing team had sensed their commercial potential. Every so often, an executive traipsed around to a bunch of banks and touted the run-throughs as a valuable service ICAP provided important clients. And so the number of recipients on Goodman’s run-through list grew. Libor submitters received it. Derivatives traders received it. Even Bank of England officials received it. Read and Goodman had realized something interesting about the mundane run-throughs. Employees at some banks—including Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, Royal Bank of Scotland, WestLB, and Lloyds in Great Britain—who were in charge of submitting Libor data sometimes appeared to simply copy ICAP’s data rather than go through the onerous process of coming up with their own hypothetical estimates of what it would cost to borrow across different currencies and time periods. … Once, when Goodman’s run-through contained a typo, suggesting six-month Libor at 1.10 instead of 1.01, Read noticed that Citigroup and WestLB copied it, even though it represented a huge leap from the previous day’s level. When Goodman corrected it the next day, the banks again followed suit. (c)Q:Nobody ever told him it was inappropriate—legally, ethically, or otherwise—to lobby outsiders for help on Libor. What kept him up at night wasn’t that what he was doing was wrong. It was that he wasn’t doing it well enough. Hayes was so open about, and preoccupied with, his strategy that he would change the status on his Facebook page to reflect his daily desires for Libor to move up or down, a self-deprecating poke at his nerdy fixation. (c)Q:In December 2007, UBS’s CEO, Marcel Rohner, gave a presentation to investors in London. Projected on a screen in front of the audience, the presentation cited “structured Libor” as one of the bank’s “core strengths” and as a “high growth/high margin business.” (c)

Michael

July 11, 2017

The most disturbing thing about this book wasn't the fraud. It was the culture that incentivized and looked the other way while the fraud was committed. I lived in this world (the world of "Wall Street") for more than 20 years. I saw the culture from the inside and Enrich absolutely nailed what it felt like. Customers are dopes to be taken advantage of; human value is determined by how much money you make and ethical values are a sign of weakness. It is insidious and takes a toll on how one views the world. That is not to suggest that there is no one in financial services with morals - I'm sure there are some. But the culture of big money banks provides ample incentive to ignore the rules created to assure fairness in the marketplace. If someone isn't smart enough to avoid being cheated, the unwritten rule states, then they deserve what they get. It is appalling how widespread the LIBOR fixing fraud was and how few were held to task for defrauding the average Joe. Yet, that has been the recurring pattern in all of the major Wall Street based financial fraud cases. Someone is singled out as the scapegoat and all the senior managers, who are aware but look the other way, get off without even a slap on the wrist. My career never crossed paths with the legions of traders and brokers who played the game of fixing LIBOR, but I recognized them all. I have seen their counterparts in other areas of the business. Part of the culture is the disturbing, but ubiquitous thinking that if everyone is doing it, it must be ok. Reading this book brought back all of those memories and was a disturbing reminder of why I ultimately left that field. Yet, I would take exception with one aspect of Enrich's story. He makes Tom Hayes (the trader at the center of the LIBOR fixing prosecution) something of an innocent. He is portrayed as someone whose Aspergers made him trust the wrong people and blinded him to the ethical right and wrong of his actions. I do not doubt that Hayes was the scapegoat in this story - the fall guy for a system and culture that wanted his gains and ignored his methods. But he is no hero. He committed fraud on a large scale. Perhaps, as Enrich suggests, he was the fly in the spider web rather than the spider. Perhaps he was the victim of others rather than the mastermind of the strategy. Nonetheless, he was guilty. He never once asked himself whether what he was doing was wrong. I don't think he deserved the sentence he received - or more accurately, I think others deserved his harsh sentence more. But there is no excuse for his actions. What is most disturbing is that the victory party at the end of the book reinforces the reality that nothing changed. Somewhere on Wall Street, someone is committing financial fraud by bending or ignoring the rules. Somewhere someone is telling themselves, "well if everyone is doing it, it must be ok." I fear that the system will never change. And perhaps that is the most frightening thing of all.

Ms.pegasus

September 08, 2021

Demands for accountability became particularly loud after the 2008 financial meltdown. In particular the cries were directed at Attorney General Eric Holder, after his “too big to fail” pronouncement. Surely someone should have gone to jail for causing such a debacle. Author David Enrich touches on that subject of accountability from a very different vantage point. He intertwines the rise of investment banking superstar Tom Hayes with competitive economic strategies crafted in London and Washington decades earlier.Prospective readers might be dismayed by the long cast of characters in the opening pages of the book. However, there are only a few key points to remember. Banks employ traders, or “market makers.” Each trader has an area of expertise – a specific currency, a country, or type of security. They rely on middlemen employed by brokerages to find a trading partner. These brokers make it their business to develop strong personal relationships with traders from all the big investment banks, in order to pitch the deal. For their matchmaking efforts they earn a commission. The more trades they broker, the more commissions they earn. The big players here will be Royal Bank of Scotland, Royal Bank of Canada, UBS, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank on the investment side and ICAP, R.P. Martin, and Tullett Prebon on the brokerage side.The inanimate entities in this drama, interest based derivatives and Libor, are even more important cast members. Enrich provides a lucid and succinct explanation of derivatives. “They were instruments whose values derived from something else. What you were buying or selling was not the thing itself (widgets, bushels, gold bars) but something related to that thing, maybe its future value, or how it compared to something totally different. If you wanted to buy ten gold bars, that was straightforward; if you wanted to place a bet that nine months from now the price difference between ten gold bars and fifty bushels of wheat would be twice the difference between five bushels of wheat and sixteen widgets, then you were playing with derivatives.” (p.31)Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate) was officially launched in 1986. Banks submitted an estimate of what interest rate each of them expected to pay for securing a short-term loan from another bank. The estimates were averaged by Thomson Reuters and reported daily. Those numbers determined either in whole or in part the interest rates of bonds, adjustable rate mortgages, and dozens of other financial products. One/one-hundredth of a percent change in Libor would move the value of a derivative valued at one million dollars up or down by $10,000. A hedge fund trader might make thousands of daily transactions resulting in gains and losses in the millions.Two events set the stage for this drama. First, the 1986 “Big Bang” – Margaret Thatcher's launch of British banking deregulation. Second, the passage in 1999 of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act in the U.S. Both events removed restrictions separating investment banks from commercial banks. Raw profit for the bank replaced customer service.In 2001 Thomas Hayes began his banking career at the Royal Bank of Scotland. He had an uncanny facility with numbers and a unique skill for designing predictive algorithms. By this time, Libor had spawned multiple variants: Tibor (the Tokyo interbank offered rate); the Euribor (the Euro version); Hibor (the Hong Kong version) and so on. Each iteration netted the British Banking Association a licensing fee, so the Association encouraged this proliferation. “Hayes organized his bets around derivatives that would deliver profits if, at a specific date, the difference between two interest rates – say, those in the United States and those in Japan – narrowed or widened by very precise margins. Hayes might wager the U.S. dollar Libor might fall relative to yen Libor.” (p.91)It soon occurred to him that since each bank's submission to Thomson Reuters was an estimate, that estimate could be tweaked up or down. All he needed were the right personal connections. An avuncular broker like Darrell Read at ICAP or Terry Farr at R.P. Martin would have just those sorts of connections and would be eager to do him “a favor” by talking to some of their banking contacts. Libor swings favored the holdings of reporting banks; and ultimately a collection of colluding traders. A deregulated banking environment, huge global transactions instantaneously effected, a key index based on subjective and undocumented “guesses,” a caste of superstar traders rewarded by the amount of money their trades generated, exchanges of kickbacks between brokers and traders for favors, and what Enrich repeatedly refers to as a “frat house culture” .... the fixes became more frequent and blatant. A little over half the book is devoted to Tom Hayes’ rise in spite of an abrasive personality oblivious of social niceties (there was a general consensus he displayed Asperger’s Syndrome characteristics). This was the most interesting part of the book. The second half chronicles a slow but inevitable downfall and surprising denials of his “friends,” colleagues, and supervisors. Enrich converts what could have been a dry financial narrative into a mind-blowing story of hubris and reckless greed. He even garners a bit of sympathy for the unrepentant Hayes. The story poses a dilemma: who exactly was culpable? Not even the foot-dragging compliance investigators can be said to be blameless.

Anirvan

April 14, 2017

This is a great work of journalism that reads like a thriller. I enjoyed it all the more because I had previously read David Enrich's reporting on Tom Hayes and his trial in the Wall Street Journal two years ago. Here's the central question: if a trader rigs Libor — the rate that determines your mortgage payments and credit card bills — would you blame him or his bosses who expect that of him, or the system where everyone who can is rigging it to make millons? What Tom Hayes did was wrong, but he was made a scapegoat while the people who rewarded him for rigging Libor rates went scot-free. Everyone who colluded with him turned around when investigators closed in and threw Hayes under the bus. The saddest part is that Hayes, a mathematical prodigy and one of the best financial traders, never realized that people he thought of as friends would not hesitate to turn on him.That doesn't mean what he did was right (a lot more of that in the book), but it does force us to question the measures taken by governments after the 2008 financial crisis. Banks paid a lot in fines, but almost all of its top brass not just escaped jail but made millions off the crisis. Something similar happened with the Libor rigging scam, where Hayes was portrayed as the ring leader of a vast criminal conspiracy when in reality he was one among many mid-level traders and brokers who were actively working to rig Libor. This book is definitely one of the best works of investigative business journalism, in the same league as "Barbarians at the Gate" or "Den of Thieves". And thanks to Enrich's excellent writing, you don't even need to know a word of financial jargon to understand it.

Sam

April 02, 2017

The Spider Network is a bonafide thriller. It's the inside story of one of the most audacious bank heists of all time. But it's also a classic of muckraking journalism that exposes how insiders can manipulate the complexities of the global financial system to enrich themselves. On another level, it's a fascinating character study of a brilliant, complex and unpredictable man haunted by his own personal demons who, with a few keystrokes, could affect the lives of billions of people. It's rare to find a book that you feel like you should read, but that you also can't put down. David Enrich is the rarest kind of writer, someone who is steeped in the arcane details of a subject few people understand, but also has the ability to step back and tell a story.

Maciej

April 06, 2019

The Spider Network is a great story of a math genius and a gang of backstabbing bankers. The book details one of the greatest scams in financial history. The author is David Enrich, a Wall Street Journal’s award-winning business reporter.In a nutshell, the scandal involves something that very few non-financial people have heard of but is enormously important. It’s called LIBOR which is an acronym that stands for the London Interbank Offered Rate. This is a kind of international benchmark that represents the interest rate at which various banks offer to lend short-term loans to one another in the interbank market. LIBOR is so important because it is the DNA for the interest rates that people around the world pay their mortgages. Credit cards, student loans or car loans are also valued by this benchmark. This is also a basis for the interest rates the multinational companies pay when they borrow money, or even when cities borrow money, their interest rates are often based on LIBOR. The LIBOR is compiled every day by a group of bankers who basically conduct an estimation of how much it costs them to borrow funds from each other. Suddenly, a bunch of bankers figured out that this rate was extremely easy to manipulate and decided to operate in order to enhance their own financial positions and make a lot of money by trading assets valued on LIBOR.The story concentrates on an analyst named Tom Hayes who is a mildly autistic mathematician and a star trader for a succession of the world’s biggest banks. Throughout his career, he makes a ton of money these banks and is heavily recruited by one bank after another as UBS, Goldman Sachs and other banks of that calibre.There are other characters portrayed in the book, nevertheless, what I would like to emphasize is that most of these guys, at the moment they arrived at the bank out of their business school, they are specially trained to basically hunt for loopholes, weaknesses and inefficiencies in order to push as far as they could every single time with the sole goal being to make as much money as they can and as quickly as they can. In that context, it is not that surprising that such scandals are rough and it is even more surprising that they are being encouraged to push as far as they can and... (if you like to read my full review please visit my blog https://leadersarereaders.blog/the-sp...)

Nick

March 13, 2017

This story is amazing. Not only were trillions of dollars worth of loans based on a Libor, but enormous amounts of derivatives contracts as well. Yet, as it turns out, Libor was easily manipulated by the traders and brokers involved in trading these derivatives. While Enrich outlines how the scandal unfolded in amazingly fascinating detail, what I really loved were the characters. You really get a feel for everyone from the regulators to the traders. I particularly enjoyed the working class partying brokers who kissed up to not only their math nerd client, but to their math nerd client's family as well. It is a real inside look into a particularly sleazy side of Wall Street culture.

Mjdrean

April 26, 2017

Usually anything financial confuses and bores me. While I admit to skimming though a good portion of the "financial" stuff, I did thoroughly enjoy the people part, the journey to exposure and the author's "novelish" approach. It also left me exhausted at the thought of the mountains of tedious research he wrangled into a superior read. In the end, I realized what I thought all along about the greedy money people is even worse.

Charlene

August 28, 2018

Captivating. Read like fiction.

Clay

May 02, 2018

The overall plot wasn't all that "Wild", but the gang was rather backstabby. Not sure if I would have classified it as "One of the Greatest Scams in Financial History" either. It was another case of letting investment bankers be in control of a market metric that they could manipulate to some degree and then make bets on how things would be in the future (where they would try to manipulate the metric in their favor). In this case the metric was Libor (London Inter-bank Offered Rate) or the average interest rate that one bank would charge another that was borrowing money from the lending bank in London. If you've read your credit card terms or adjustable mortgage terms, you've seen Libor referenced as a basis for setting those adjustable rates. The original metric proved so useful, a whole host of other countries with their banks and currencies created similar metrics. From this, derivative products could be bought by investors to hedge other investments in their portfolio. Brokers and traders that sold these derivatives often took up opposite positions to balance or hedge their risk. Unfortunately, the "foxes were in charge of the hen house" in many cases and brokers could influence trends in the Libor-like metrics. The author does a good and simple explanation about Libor, its history and uses, and the concept of derivatives and making "bets" on how much Libor changes within a given period of time. These latter "financial products" were the crux and motivation for the whole scam. All in all, one more reason for stricter banking regulation and prosecution, IMO.

Cheryl M-M

March 28, 2017

Enrich has collaborated with and interviewed Tom Hayes quite extensively for this book. So it’s not surprising that the book is slightly slanted in his favour, especially when it comes to the mitigating circumstances for his actions.Readers should note that Hayes launched an appeal against his conviction in January 2017, and his defence is built on the grounds that he believes he did not have a fair trial. In his previous trial the judge wouldn’t allow his Asperger’s diagnosis to be taken into account or presented. His expert witness argues that the Asperger’s syndrome would explain his inability to see his conduct as dishonest or that others could perceive his conduct to be dishonest.It is also worth noting that Hayes wasn’t diagnosed with Asperger’s until before his trial, so it kind of begs the question whether this is just a convenient excuse and/or basis for his diminished capacity of guilt defence.Of course the other side of the coin is the fact that Hayes, his colleagues and indeed the entire financial industry functioned and worked in an environment with little or no restrictions or repercussions. Most of the dealings we now consider to be criminal were not considered to be so at the time they began using them. A perfect example of this is insider trading, which was once, not many decades ago. considered to be normal wink wink nudge nudge dealing between traders and brokers.I think the Spider Network is an inside window into the world of big finance and the insidious nature of those at the top. The Libor rate is an easily manipulated money sucking scam created by rather greedy, but extremely clever men with masses of hypothetical money at their fingertips and no thought to the lives they might, and certainly did, destroy.It has been noted that there are plenty of sociopaths in the world of big business and finance. They are capable of making ruthless decisions without being hindered by empathy and compassion. They don’t consider the moral implications or the little man at the bottom of the pyramid.Whilst the story of who, how and what is fascinating it also important to remember all the people who have fallen prey to the Libor rate game of derivatives.On a side note I would like to add that despite Enrich giving the reader an inkling of who Hayes was and is, especially in regards to his ASD and possible vulnerabilities, the picture isn't complete. The complexity of the case against him and why he is appealing isn't delved into as minutely. Enrich does leave one with food for thought though, especially if you think out of the box. Was Hayes really the spinning spider or just part of the silky web, which was considered disposable?*I received an ARC of this book courtesy of the publisher via NetGalley.*

Canadian

May 04, 2022

Bankers gone so wrong...again. A great story of how a small coterie of players was able to distort the LIBOR (interbank lending rate) to allow them to make money off trades. Really well written, lays out how a small number of traders just kind of....fell into it. No grand plan at work, really. And how messed up that is. Oversight within the financial institutions themselves seems incredibly lax. And, not all those involved paid the price...except of course, a number of investors harmed by the market distortion. Yet another great tale of perfidy in the markets, accessible to lay readers.

Doug

July 17, 2018

When I was a junior corporate lawyer, I sat in a debt training session. One of the partners mentioned LIBOR. The explanation confused me. But as a young lawyer I didn't know very much about the workings of high finance.It turns out that the benchmark is hodgepodge of figures voluntarily submitted by banks with little market check or control. I've heard plenty of stories in the news. For a detailed look, I recently read The Spider Network: The Wild Story of a Math Genius, a Gang of Backstabbing Bankers, and One of the Greatest Scams in Financial History.LIBOR—the London interbank offered rate, determines the interest rates on trillions in loans worldwide. LIBOR is supposed to reflect the interest rate at which member banks could borrow from one another that day. LIBOR is a global benchmark used to price all types of debt from credit cards, to variable rate mortgages, to complex derivatives and to corporate loans.Very few people knew exactly how the rate was calculated. (That included that partner giving my training.) Even among the member banks there was widespread confusion as to its exact definition.David Enrich of The Wall Street Journal manages to make Libor interesting in The Spider Network. His key to the story is telling the story of UBS interest rate derivative trader, Tom Hayes. This socially inept, if not autistic guy, is set up to be the fall guy for the LIBOR scandal.Banks had lots of internal conflicts on their LIBOR submission. The rate a bank submits is indication of its credit worthiness. If it submits a rate that is higher than its peers, people may wonder if there is a problem at the bank.The other major conflict is that the banks have traders, like Tom Hayes, who could make money or lose money on their positions depending on whether LIBOR goes up or down.“LIBOR is a widely utilized benchmark that is no longer derived from a widely traded market. It is an enormous edifice built on an eroding foundation—an unsustainable structure,” stated CFTC Chairman J. Christopher Giancarlo in his opening remarks at the CFTC’s Market Risk Advisory Committee meeting last week. At the same meeting Commissioner Rostin Behnam identified noted that “LIBOR has been subject to pervasive fraud, abuse, and manipulation. Since June 2012, the CFTC has levied sanctions of more than $3.3 billion for LIBOR-related misconduct.”I would recommend The Spider Network to learn more about the LIBOR mess.

Helen

April 10, 2017

This is a fascinating in-depth look at the people behind the Libor financial scandal. In particular it examines how Tom Hayes, one of the only people jailed for his part in the rate-rigging, came to be involved. Hayes, of course, is intent on appealing his sentence, so it remains to be seen if the outcome for him will change.First up, it's important to note that I didn't know much of anything about trading, derivatives or Libor before I started this book. I'm also one of those readers who flushes out half of all knowledge attained as soon as I finish a book. But I still enjoy the journey for some reason.Enrich does well to make a difficult subject accessible. I wouldn't say it's an immediately compelling read. It's not a page turner, more of a slow burn of interestingness (I know words, me). There aren't twists and turns so much as a deepening of understanding, a realisation as the book goes on as to how many people were implicated in the scandal and how so many got off completely scot-free.The author worked closely with Hayes, which I think makes Hayes somewhat sympathetic as a result, but only because you understand him more, not because he's painted as completely innocent. This is a man who may or may not be on the Asperger's Spectrum (and armchair diagnosis while reading a book would suggest he could be) but very clearly takes the wrong course of action for his own benefit, over and over again, steamrollering over friends and colleagues. I say friends - but of course he didn't have any genuine ones apart from his wife. Ultimately, it's the tale of a man who determined to earn as much as he could for both himself but also his bosses. His bosses authorised what he did multiple times. Firms fought over this man precisely because of what he did with Libor! He never stopped to think of the consequences but he also never hid what he did, not really. That's why there was so much evidence against him. He thought he was doing his job, because the sector is/was so corrupt that earning as much as you could any way you could, was his job. I don't exactly feel sorry for him, but he is obviously just one piece of the network manipulating Libor.An enjoyable read, if you like complex stories about sectors you don't fully understand!

Dave

July 17, 2017

This is how its done. Get the inside source who spills his guts then shape a narrative around it. Tom Hayes went to jail for 14 years before that he dominated the Tokyo currency market. In order to dominate that he needed libor to go his way like so many traders in the currency / interest / credit world of the oughts. As banks did more prop trading and pushed risk the pressure to move libor got larger. Libor was subject to widespread manipulation since 1991. What Hays did differently is engange in switch trades to curry favor with the libor setters. The switch trades had no business reason except to manipulate but they require three parties to pull off. Hayes, another trader and a broker. Hayes used multple brokers to pull these trades - a network of fraud. When the markets crashed in 2007-2008 it was obvious that libor was a joke. It didn't crash or seize up like everything else. Hayes made a killing in 08 because libor didn't tank, it didn't tank because it was made up rate. The second scam in this story is how once the scheme was expose - wide spread industry manipulation - everyone conspired to make Hayes the fall guy. That's the tragedy in the whole thing. Hayes did his dirt and is not without fault, but mildly autistic he missed all the social cues that he was not the spider but the fly. Best book out of the 2008 crisis i've read. I read this whole 460 page book on a Saturday.

Most Popular Audiobooks

Frequently asked questions

Listening to audiobooks not only easy, it is also very convenient. You can listen to audiobooks on almost every device. From your laptop to your smart phone or even a smart speaker like Apple HomePod or even Alexa. Here’s how you can get started listening to audiobooks.

- 1. Download your favorite audiobook app such as Speechify.

- 2. Sign up for an account.

- 3. Browse the library for the best audiobooks and select the first one for free

- 4. Download the audiobook file to your device

- 5. Open the Speechify audiobook app and select the audiobook you want to listen to.

- 6. Adjust the playback speed and other settings to your preference.

- 7. Press play and enjoy!

While you can listen to the bestsellers on almost any device, and preferences may vary, generally smart phones are offer the most convenience factor. You could be working out, grocery shopping, or even watching your dog in the dog park on a Saturday morning.

However, most audiobook apps work across multiple devices so you can pick up that riveting new Stephen King book you started at the dog park, back on your laptop when you get back home.

Speechify is one of the best apps for audiobooks. The pricing structure is the most competitive in the market and the app is easy to use. It features the best sellers and award winning authors. Listen to your favorite books or discover new ones and listen to real voice actors read to you. Getting started is easy, the first book is free.

Research showcasing the brain health benefits of reading on a regular basis is wide-ranging and undeniable. However, research comparing the benefits of reading vs listening is much more sparse. According to professor of psychology and author Dr. Kristen Willeumier, though, there is good reason to believe that the reading experience provided by audiobooks offers many of the same brain benefits as reading a physical book.

Audiobooks are recordings of books that are read aloud by a professional voice actor. The recordings are typically available for purchase and download in digital formats such as MP3, WMA, or AAC. They can also be streamed from online services like Speechify, Audible, AppleBooks, or Spotify.

You simply download the app onto your smart phone, create your account, and in Speechify, you can choose your first book, from our vast library of best-sellers and classics, to read for free.

Audiobooks, like real books can add up over time. Here’s where you can listen to audiobooks for free. Speechify let’s you read your first best seller for free. Apart from that, we have a vast selection of free audiobooks that you can enjoy. Get the same rich experience no matter if the book was free or not.

It depends. Yes, there are free audiobooks and paid audiobooks. Speechify offers a blend of both!

It varies. The easiest way depends on a few things. The app and service you use, which device, and platform. Speechify is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks. Downloading the app is quick. It is not a large app and does not eat up space on your iPhone or Android device.

Listening to audiobooks on your smart phone, with Speechify, is the easiest way to listen to audiobooks.